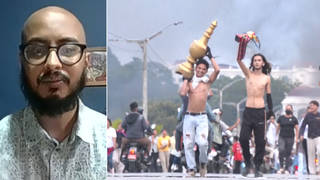

In Bolivia, an attempted military coup against President Luis Arce was quickly thwarted soon after it began Wednesday night. Arce, part of the left-wing Movement for Socialism (MAS) party, has already named a replacement for the coup’s leader, General Juan José Zúñiga, who called for “democracy” during the attempt. Arce was elected in 2020 after the third reelection of Bolivia’s previous president, Evo Morales, one of the founders of MAS, for an unconstitutional fourth term was overturned by pressure from the military and police. Although Bolivia is “a fragile democracy,” there is “very little popular support for the military,” while popular civilian support remains with Morales and MAS, explains our guest Kathryn Ledebur, executive director of the Andean Information Network in Cochabamba.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: In Bolivia, thousands filled the streets of the capital La Paz Wednesday to confront military forces who tried to carry out a coup against democratically elected President Luis Arce.

PROTESTERS: ¡Fuera, fuera, fuera, fuera, fuera, fuera, fuera, fuera, fuera, fuera!

NERMEEN SHAIKH: ”¡Fuera!” or “Get out!” people shouted at military forces. Bolivian President Arce addressed the protesters.

PRESIDENT LUIS ARCE: [translated] It fills us with bravery, courage to keep resisting, to keep on resisting any coup attempt, because Bolivia deserves its democracy, which has been won in the streets and with blood brothers and sisters.

AMY GOODMAN: Hours after the failed coup, Bolivian authorities arrested rogue military commander General Zúñiga and his alleged co-conspirator, Navy chief Juan Arnez. Meanwhile, President Arce has sworn in new heads of the Army, Navy and Air Force.

For more, we go to Cochabamba, Bolivia. We’re joined by Kathryn Ledebur, director of the Andean Information Network.

Kathryn, welcome back to Democracy Now! Can you explain what just took place on Wednesday in Bolivia?

KATHRYN LEDEBUR: Thanks, Amy.

Well, it’s very hard to explain. You know, we had tanks filling the main plaza in front of the government palace. This all happened, you know, a little bit after lunch at 1:30 p.m. This is after very strong statements from an army commander, the top army commander, Zúñiga. And, you know, this unexpected rush of tanks and of military personnel, that really harked back to the 2019 coup, that’s still very fresh in Bolivia’s memory.

They forced their way into the political palace. Zúñiga demanded the release of coup — the 2019 coup political prisoners, such as Fernando Camacho and Jeanine Áñez, made the obligatory reference to his testicles, always a part of a macho military move. And somehow, the conflict, within a number of hours, defused. And Zúñiga walked away, and Arce swore in new military leaders.

But, you know, this is a military that’s accustomed to having coups. It’s a military — it’s a country that’s had more military coups than any other Latin American country. And we see here that the Bolivian Armed Forces are firmly entrenched in democracy still, and that the consequences of 2019 and the impunity that continues has really been corrosive here.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Kathryn, if you could explain: Why this attempted military coup now? And what was the relationship between President Arce and the military chiefs?

KATHRYN LEDEBUR: Well, we’re at a point in time where the Arce government is under a great deal of pressure. There’s an economic crisis. The state lacks a lot of resources because of a great reduction in the income from oil and gas revenue, while the state has to continue to pay for imported petroleum at increasingly higher prices. So we have empty government coffers. We have a right wing that’s discontent. We have a crisis with the constitutional — Bolivian Constitutional Court extending its own mandate illegally, and that of the Supreme Court, and blocking judicial elections that are mandated by the Bolivian Constitution.

You have the carryover from the 2019 coup. And really, after that coup, although some military officers have been prosecuted and jailed, there hasn’t been any restructuring of the Armed Forces. There hasn’t been a fundamental change in vision. And I think that Arce, perhaps with the best intent, does not understand security issues very well. Remember that he was Morales’s finance minister. And I don’t think he’s been particularly strategic in the choices that he’s made for military commanders.

And so you have an institution that appears to be not firmly under democratic control, a government that is feeling pressured and cornered. And at the same time, there’s an intense conflict within the MAS party, a strong divide between Arce and his former boss, three-time President Evo Morales, that is also leading to greater uncertainty here in Bolivia.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about what the general was alleging, that this was an auto golpe — right? — a self-coup, that he was carrying out the wishes of Arce? How outrageous or reasonable is this?

KATHRYN LEDEBUR: Well, Amy, it’s impossible to say. It’s a quite confusing situation. I’ve never actually seen a coup attempt that began at 1:30 and ended at the end of the Bolivian workday, promptly at 6:30. You know, he had made very — Zúñiga had made very strong threats about arresting Evo Morales, Arce’s now political opponent. And it wasn’t clear whether or not he had been fired. But no one saw this coming, particularly. You know, suspicions arise because Zúñiga, who was never a stellar officer, was handpicked for promotion to general and then Army commander by Arce. They play basketball together. They have a close personal rapport. And he was perceived to be Arce’s strongest ally within the Bolivian military. So, it’s not clear whether things soured or what exactly happened.

But it was interesting, because, generally, in a situation like this, bullets are fired to impede the military from coming into the statehouse. That didn’t happen in this particular case. And Zúñiga was not arrested at the time. He walked away from the main plaza, or drove away, and was only arrested later that evening. So, it’s a very bizarre framework for a coup attempt.

Zúñiga’s affirmations are problematic. I think we have to put them in the context of his position. But it’s a very unusual form of coup attempt. And it’s going to be very interesting to see how this plays out. There was no — there were threats of violence, but no actual violence. It’ll be interesting to see in the coming days how this evolves.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: You said earlier, Kathryn, that President Arce was not so strategic in his choices of military chiefs. What is your assessment now of the people he’s appointed?

KATHRYN LEDEBUR: I think it remains to be seen. I haven’t been able to look into their particular military career. But it’s — you have a defense minister who was a Morales minister, but in another area. I don’t see that the Arce administration’s strong suit is security issues or reform of the security forces. And I think there dramatically needs to be an intense, profound reform of both institutions, both institutions that received payment in 2019 to disobey Morales and to support a right-wing uprising.

So, we’ve had these inherited long-term problems that aren’t being addressed. We’re seeing cycles of coups throughout Bolivia’s history, but — or cycles of military commanders that make assertions, maybe fired, maybe arrested, maybe imprisoned, but we don’t see a profound change within the institution itself. And I think that’s highly problematic. And I think that that’s probably an issue in most Latin American countries.

AMY GOODMAN: So, presidents across the political spectrum in Latin America condemned this attempted coup. Can you talk more about the role of the former president, Evo Morales, that he plays in the current politics of Bolivia, Kathryn?

KATHRYN LEDEBUR: Yes. I think the support from Latin American countries was crucial, and it was rapid. I think it’s important to highlight that a very bland, watered-down message came from the Biden administration. And, of course, we’re beginning to become used to that.

You know, Morales handpicked Arce, who was elected by an overwhelming majority in the 2020 elections, after the violence, the incompetence and the corruption of the interim Áñez government that was illegally put in by the military, with the support of the Trump administration. But as Arce’s administration has progressed, Morales has become an outspoken critic, for a number of reasons.

The perception — you know, MAS, the MAS party, was originally considered a coalition of grassroots organizations, social movements, unions, that had direct input with the executive. And the perception from the Morales administration is that most of the Arce ministers are upper-middle-class men that are personal allies of Arce but don’t necessarily represent social movements. And, in fact, when there have been protests about different ministers, and requests from grassroots organizations that those ministers have been changed, Arce has maintained them in power. So, there’s one key issue there.

There’s another key issue about the stigmatization of the Chapare coca-growing zone by the Arce administration, tagging it again as the center of drug trafficking, as the U.S., the DEA and far-right governments have, that has promoted a lot of friction; criticisms from Morales on the way that the Arce government has dealt with oil and gas administration, economic administration, the disappearance of dollars in the Bolivian economy, and fuel shortages that have affected the government.

So, there’s been an impasse between the two sides of the MAS government that other progressive governments around the continent and the Grupo de Puebla have worked very, very hard to try to overcome. And this divide has become increasingly greater. It’s something that’s very worrisome as we come to the 2025 elections and the suggestion that the right may well come into power.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, Morales’s response to this coup, and where you think it goes?

KATHRYN LEDEBUR: Well, it’s interesting that Morales’s response was one of the first responses. He was the first person, or one of the few people originally, to denounce a troop movement, an unexplained movement of troops in La Paz that was worrisome. And he also denounced the coup attempt, and he denounced it vigorously. And then Arce denounced the same thing. And so, seeing the troop movements, seeing the tanks in the plaza, seeing the soldiers filing in, it was very, very worrisome. And Morales expressed those sentiments, even before Arce. So, I think at that point in time, there was actually — it’s the first time they’ve agreed on anything in months.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Kathryn, before we end, if you could say — you hinted at this earlier in one of your responses. If you could explain what the — first of all, how much support President Arce still has among people, and what the both class and physical divides are, the highlands versus the lowlands, poor versus rich, in terms of support for President Arce, and perhaps also some who support the military?

KATHRYN LEDEBUR: Well, I would say that there’s very little popular support for the military in Bolivia. I mean, they poll very badly. They poll even worse after coup attempts. The same is true for the Bolivian police force. This was something that I don’t perceive had any popular backing. You know, the Bolivian citizenry do not want to return to violence, gross human rights violations and states of siege.

But Arce is facing a lot of difficulty also about the not calling out or denouncing the High Court’s self-extension of their mandate, something that’s completely illegal. And then having the Constitutional Court rule in favor of Arce is something that’s been a great problem by — signaled by the other side of MAS, by justice experts and even by the opposition.

So, you know, it’s a bit — Arce is in a very delicate position. He perhaps has received a respite from the pressure for six weeks, perhaps, with the relief of the population that democracy has been maintained. But it’s a fragile democracy. And I think that in the long run, this incident has — will bolster Arce in the short term, but demonstrates a vulnerability that we should all be concerned about in the long run.

AMY GOODMAN: Kathryn Ledebur, we want to thank you so much for being with us, director of the Andean Information Network in Cochabamba, Bolivia, researcher, activist and analyst with over two decades of experience in Bolivia. To see our interview in Spanish, go to democracynow.org and click on Spanish, Español. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

Media Options