Guests

- Marianne Hirschprofessor emerita at Columbia University.

Columbia University professor Marianne Hirsch’s new article in The Forward is titled “I grew up under a terrifying authoritarian regime. Mahmoud Khalil’s arrest is right out of their playbook.” She tells Democracy Now! that seeing footage of the ICE arrests of Khalil and Tufts University student Rumeysa Ozturk “brought back these feelings of terror that I had as a child.” Hirsch grew up in Romania under the authoritarian regime of Nicolae Ceaușescu and says she sees parallels between the climate of fear she was raised in and the repression of speech and protest on campuses today. Hirsch, who is Jewish, condemns the “anticipatory capitulation” of universities, like Columbia, to the Trump administration’s threats to pull funding and says “the reason for this was never to fight antisemitism, but it was to decimate academia.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: “There’s a nip in the air … It’s the chill of fear and despair that is all too familiar to me. The recent Columbia graduate student Mahmoud Khalil’s detention by Immigration and Customs Enforcement on Saturday has brought back my most tormenting childhood nightmares as a child of Holocaust survivors in Communist Romania in the 1950s.”

Those are the words of our next guest, Marianne Hirsch, professor emerita at Columbia University, in her recent article headlined “I grew up under a terrifying authoritarian regime. Mahmoud Khalil’s arrest is right out of their playbook.” The article was published in the Jewish newspaper The Forward.

AMY GOODMAN: Marianne Hirsch joins us today in studio. She’s the author of several books, including The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust.

Professor Hirsch, welcome to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with us. You said the conditions for Mahmoud Khalil’s arrest were created by Columbia. And then put that into the larger context, you having come out of authoritarian Romania.

MARIANNE HIRSCH: Well, I grew up in Romania until the age of 12. My parents were survivors of the Romanian Holocaust. And when Mahmoud Khalil was abducted, when Rumeysa Ozturk was abducted and I watched those videos, it brought back these feelings of terror that I grew up with as a child, the helplessness in front of seemingly all-powerful forces that couldn’t be stopped, that were arbitrary and that had only the barest rationale for — or no rationale for — these arrests.

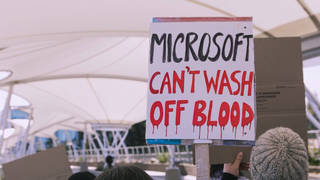

I think the condition for these arrests have been created by our universities. Unfortunately, Columbia, where I teach and where I’ve taught for 20 years, was the model for this. And the way they’ve been created is, first of all, by accepting and then promoting the big lie that antisemitism is driving protests against the brutal genocidal war in Gaza, of Israel on Gaza, that these are antisemitic protests, of excluding and suspending student groups, of draconian measures of punishment, but also of casting protesters as terrorists, which is now expanding.

And what I’m seeing spread is the kind of helplessness that I felt as a child and that I picked up from my surroundings, the fear of speaking, the suspicion that one can be denounced, that there are lists out there, that we don’t know who is on the lists, that there’s nothing that can be done to help. And I’m seeing my students silence themselves, being afraid to speak, wondering who might be denouncing them, who might be making lists.

And let’s be real, I mean, Mahmoud Khalil was chosen by Columbia to be a mediator between the administration and the student protesters, and then he was denounced by, unfortunately, I have to say, people at Columbia. There’s an Intercept report, that I’m sure you’re aware of, that there’s a group of parents, alumni and even some faculty who are making lists of students who could be deported or who are aliens, enemies of the state, of the university.

And this idea of denunciation is something that I’ve carried from my childhood, because my father would often come home saying that he was asked by his superiors at work whether he would name the names of people who — whatever — I mean, there was always a reason for this — and how he refused and how he gave up some possibilities of advancement by refusing to name those names. So, this is something I was carrying.

But there is a difference. You know, we have laws. This is illegal. And there are possibilities of appeal. And there are also ways in which this narrative, this big lie of rampant antisemitism that universities have accepted and even promoted by forming task forces on antisemitism — I think there are people who are now seeing — Jerry Nadler is a great example — that this might not have been such a good idea, because it’s brought upon us this terrible repression under the guise of fighting antisemitism. And I think people are now seeing that this is not just morally completely wrong and corrupt, but that it’s also not good for Jews, certainly, but that it’s not good for anybody, and that the reason for this was never to fight antisemitism, but it was to decimate academia.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And if you could talk — you’ve also written a piece on the extent to which and the speed with which Columbia completely capitulated or submitted to the Trump administration’s demands. You wrote a piece headlined “There’s a bleak historical explanation for why Columbia’s capitulation to Trump is so concerning,” in which you write, quote, “We are not living in early Nazi Germany. But, although as a student of fascism and the Holocaust I have learned to be careful with such comparisons, some resonances are too obvious to ignore.” What are those resonances?

MARIANNE HIRSCH: Well, the resonances are that autocratic regimes go after education, I mean, certainly higher education. Why? Well, academic freedom, self-governance, inquiry, open inquiry, the possibility that we might promote a narrative of history that is true but that doesn’t conform to the vision of the autocrat — all of those things are extremely threatening. And we’ve seen it not just in early Nazi Germany, but certainly in Hungary, in Turkey, in India, the crackdown on universities.

But what’s more concerning to me is the response of universities and how they’ve — not just anticipatory obedience, but really anticipatory capitulation, first through these task forces and accepting the antisemitism narrative, but then agreeing to the demands, which are completely illegal and unreasonable demands, in the hope of pacifying the autocrat, which I think everybody already should know that that is not how you can deal. So, what I’m not seeing is solidarity among universities, the willingness or the eagerness to fight back and to say, “No way, we’re not going to stand for this.”

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And finally, Marianne, you’ve worked on the transmission of memories of violence across generations, what you call “postmemory.” How do you see that? You’ve expressed concerns, in particular, Mahmoud Khalil’s unborn child, the children of Gaza. How do you see this kind of being acted out now and in the future, all the violence that we see happening now? And also, I should mention the hundreds of student visas, that we know of, of international students that have been revoked.

MARIANNE HIRSCH: Well, this revocation, just to start with that, completely arbitrary, and students are not even informed, and the university is not informed. They find out through the online system. And then, the ostracism of these students, which is what happened to me as a child, and certainly to my parents, of being denationalized, of being ostracized and publicly shamed for — you know, as a child, I was a Pioneer, with the red scarf, and I saw some of my classmates were — their red scarves were removed, forcibly removed, in front of the entire school when their parents applied for visas to leave the country. So, that’s something I carry as a child.

But I’m also carrying what I call postmemory, which is memories of violence across generations that I inherited from my parents’ stories. These are vicarious, but they feel like memories. And that’s why I thought I needed a term for these very powerful fears and terrors that children — you know, that we inherit for experiences that we didn’t ourselves live, but that we feel like we remembered.

So, I guess the fear right now is that it’s not only the children right now, but it’s the future generations that will — how they will receive this moment of fear that is spreading across the country, with people losing visas, losing status, even the stories of green card holders, but citizens, possibly, and naturalized citizens like me, possibly being denationalized, and like you. So, I think the reverberations of this —

AMY GOODMAN: We have 20 seconds.

MARIANNE HIRSCH: — could reach future generations. And what we’re transmitting is extremely concerning to me, and I hope we are transmitting resistance, resilience and refusal.

AMY GOODMAN: Marianne Hirsch, we want to thank you so much for being with us, Columbia University professor emerita. Her recent piece in The Forward, “I grew up under a terrifying authoritarian regime. Mahmoud Khalil’s arrest is right out of their playbook.”

That does it for our show. I want to wish a happy birthday to David Prude and a belated happy birthday to Matt Ealy! Our condolences to our executive director, Julie Crosby, on the passing of her aunt, and also to Nermeen Shaikh on the passing of her dad. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

Media Options