Guests

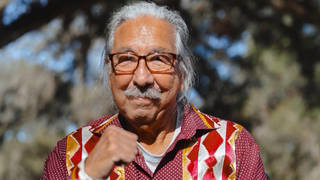

- James AnayaU.N. special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples. He is also professor of human rights at the University of Arizona College of Law.

James Anaya, the U.N. special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, has conducted the United Nations’ first-ever investigation into the plight of Native Americans living in the United States. Anaya’s recommendations include advising the U.S. to return some land to Native American tribes, including South Dakota’s Black Hills, home to the famous Mt. Rushmore monument. Anaya says such a move would be a step toward addressing systemic discrimination against Native Americans that continues to this day. “The indigenous peoples of this country … suffer from poverty, poor health conditions, lack of attainment of formal education [and] social ills at rates that far exceed those of other segments of the American population,” Anaya says. “These conditions are related to a history of wrongs that they have suffered.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: A United Nations investigator has said the United States should restore some land to Native American tribes, including South Dakota’s Black Hills, which is home to the famous Mount Rushmore monument. In recent weeks, James Anaya, the U.N. special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, conducted the U.N.’s first-ever investigation into the plight of Native Americans living in the United States. Anaya has called on the United States to return some land stolen from Native American tribes. Anaya said such a move would be a step toward addressing systemic discrimination against Native Americans that continues to this day. There are approximately 2.7 million Native Americans living in federally recognized tribal areas in the United States.

AMY GOODMAN: We go now to Tucson, Arizona, to speak with James Anaya, the U.N. special rapporteur, who recently concluded his tour across the United States. He is writing a report on his findings. He’s also a professor of human rights at the University of Arizona College of Law.

Professor Anaya, welcome to Democracy Now! Can you talk about what you found and what you are calling for?

JAMES ANAYA: Well, first of all, good morning. It’s good to be on the program.

What I found are vibrant communities, indigenous communities throughout the country that are striving to survive as distinct peoples with their cultures intact, transmit those cultures to future generations, but they face a number of challenges. The indigenous peoples of this country—the Native Americans, American Indians, Alaskan natives, native Hawaiians—suffer from poverty, poor health conditions, lack of attainment of formal education, social ills, at rates far that—that far exceed those of other segments of the American population. And these conditions are related to a history of wrongs that they have suffered, that most Americans are familiar with.

What I’ve called for are for the initiatives that are in place to be strengthened, the initiatives that are being promoted by the federal government through various agencies, that are being promoted by the White House itself, that are grounded in some pieces of legislation, that these be strengthened, and that there be more concerted moves towards real reconciliation with the country’s indigenous peoples.

And as part of those initiatives, what I’ve said is that the restoration of lands should be put on the table, as indeed it already is. What we’ve seen recently are efforts by the federal government to return to indigenous peoples control over certain areas—for example, most recently, an area in South Dakota that has been under the administration of the National Park Service, an area that was taken over from Native Americans during World War II for a military gunnery and really was an ongoing part of dispossession of land from Native Americans. And right recently, there’s been an agreement between the Department of Interior and the Oglala Sioux Tribe to establish what would be an Oglala national park, in essence, an Oglala-run national park. And so, that kind of initiative, restoring to indigenous peoples control over lands that are important to them, that were wrongfully taken from them, would be the kind of reconciliation process that the federal government itself and Congress itself has said needs to take place. So what I’ve called for is the strengthening of these kind of initiatives.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, James Anaya, as you say, the horrific record of the United States, in terms of constantly making treaties and breaking them and taking Native lands, is part of the worst aspects of American history. But the headline-grabbing part of your report is this issue of Mount Rushmore and the Black Hills. Could you talk about the particularities of that case and why you think that rises to the point that should actually be considered for the government to return that particular land?

JAMES ANAYA: I’m not sure why that has grabbed the headlines so much. I simply, in a press conference in Washington when I concluded my visit, referred to the Black Hills as an example of an unsettled claim. The Black Hills were taken illegally from the Lakota people, and that was acknowledged by the United States Supreme Court itself. Compensation was offered, but the Lakota people have refused to take the money because of the significance that the Black Hills hold for them. And what I’ve said is that that issue should be addressed and that ways should be explored by which control or a reconnection, some kind of restoration, should occur—could occur, by which the Lakota people could have a greater access to the Black Hills, be more present there, and that place represent again a part of the people, the Lakota people, as opposed to simply representing their defeat and the negative side of history.

Now, I haven’t said anything about Mount Rushmore. Mount Rushmore could stay under federal control, or it could be part of a joint management between the federal government and the Lakota people. There are all kinds of possibilities. I’ve simply said that this matter needs to be looked at as part of the reconciliation that Congress itself says needs to take place.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you give examples of where land was given back?

JAMES ANAYA: Well, I’ve given one that’s occurring right now, or where initiatives are in place to do just that, and that is the restoration to tribal control of a national park in South Dakota, the Badlands National Park, part of that park that was taken, as I said earlier, for a gunnery during World War II. The initiative to return that to tribal control, that’s ongoing and isn’t completed, but the Interior Department has announced an agreement between the government and the Oglala Sioux Tribe to move forward with that.

AMY GOODMAN: James Anaya—

JAMES ANAYA: Another example is—

AMY GOODMAN: Go ahead.

JAMES ANAYA: Yeah, another example is the return of the sacred Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo in 1970, an area that was taken from them that was remain—was and remained and still is sacred to them and a part of their identity and culture. That area of this sacred place was returned to them.

Then there’s another example of the—for the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe in the Death Valley area of California, Nevada. Lands that were within—that previously were within the national park of that area, that Death Valley area, were returned and restored to the Timbisha Shoshone people. These are practical steps that can be taken that are not to the detriment of any American and really are to the advantage of all of America, because they promote that kind of reconciliation that needs to take place and that is just.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, James Anaya, as you were going around the country, what kind of cooperation did you receive, either from federal agencies or from Congress, in terms of your investigation?

JAMES ANAYA: I’m sorry, I missed that. The earpiece slipped a little bit.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I said, as you were going around the country, what kind of cooperation, or lack of cooperation, did you get from federal agencies or members of Congress?

JAMES ANAYA: The cooperation from the federal government was superb, really. In fact, to do this kind of exercise, this kind of mission, as we call them, I require, I need the consent and cooperation of a country. I cannot simply go into a country and engage in an examination of issues concerning indigenous peoples without that consent. And ideally, I need the cooperation. And I did receive cooperation from the administration. I met with all the federal agencies that I asked to meet—with which I asked to meet. And I also met—was able to meet with some state officials, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: Members of Congress?

JAMES ANAYA: No, I wasn’t able to meet with members of Congress. I did request to meet with members of Congress, but for some reason that didn’t happen.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, this was the first such inquiry, fact-finding mission like this, in U.S. history? Is this right? Why now?

JAMES ANAYA: Well—excuse me, there’s something wrong with this earpiece.

The U.S. has endorsed the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. That is a declaration by the U.N. General Assembly affirming the rights of indigenous peoples to self-determination, to their lands and resources, to maintain their culture, to redress for historical wrongs. And that endorsement by the United States, which reversed the previous position of the United States, was an important point, I think, of engagement by the United States with the international community over these issues. And so, I approached the United States about a possibility of a visit, of coming to the United States and going throughout the country to examine conditions, and the government welcomed this initiative. And so, my hope is that this will be an exercise that will help promote those kinds of initiatives that need to be taken, that—and, to a significant extent, are being taken to address the concerns of indigenous peoples. But like I said, more needs to be done.

AMY GOODMAN: We want to bring into the discussion, with James Anaya, Dalee Sambo Dorough, an Inuit from Alaska who teaches political science at the University of Alaska-Anchorage, one of hundreds of indigenous leaders and activists who have gathered here this week in New York at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. She is vice chair of the forum.

Media Options