Related

Topics

Today is the fortieth anniversary of Bloody Sunday–the historic voting rights march in Selma, Alabama when used billy clubs, tears gas and cattle prods to stop some 600 black marchers from reaching Montgomery in a bid for voting rights. We go to Selma, Alabama to speak with Joanne Bland, of the National Voting Rights Museum who attended the march 40 years ago. [includes rush transcript]

Today is the fortieth anniversary of Bloody Sunday–the historic voting rights march in Selma, Alabama.

Thousands walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge this past Sunday to commemorate the anniversary. Among the marchers were Coretta Scott King–the wife the Rev. Martin Luther King. She said, “The freedom we won here in Selma and on the road to Montgomery was purchased with the precious blood of many.”

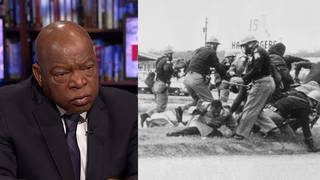

On March 7, 1965, Alabama State Troopers and Dallas County Sheriff’s deputies used billy clubs, tears gas and cattle prods to stop some 600 black marchers from reaching Montgomery in a bid for voting rights.

A second march two weeks later, under the protection of a federal court order and led by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., went 50 miles from the bridge over the Alabama River to the steps of the state Capitol in Montgomery.

Among those attending commemoration ceremonies this weekend were Georgia Congressman John Lewis, singer Harry Belafonte, the Rev. Jesse Jackson and Lynda Johnson Robb, whose father, President Lyndon Johnson, signed the Voting Rights Act into law in 1965.

Speaking on Sunday Lewis said, “President Johnson signed that act, but it was written by the people of Selma.”

- Joanne Bland, Executive Director of National Voting Rights Museum. She joins us on the line from Selma, Alabama.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We’re joined now on the phone by Joanne Bland, executive director of the National Voting Rights Museum, joining us on the line from Selma, Alabama. Welcome to Democracy Now!

JOANNE BLAND: Good morning. How are you?

AMY GOODMAN: It’s very good to have you with us. You were there 40 years ago?

JOANNE BLAND: Yes. I was. And here we are today, 40 years later, talking about it.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about what happened 40 years ago, March 7, 1965?

JOANNE BLAND: Please remember that I was only 11 years old in 1965. The ins and outs in why we were there, I have no idea. My grandmother began taking us to mass meetings when I was eight years old. And so, I guess I should say I grew up in struggle. I thought it was a way of life. But today, 40 years ago, March 7, I was at Brown Chapel AME Church, which is my church. I grew up in that church, but my sister was inside. I had no idea that there may be some violence. I probably was outside. As I said, I was only 11. But when the marchers lined up, I got in the line, because my sister made me, and she wanted me to stay with her, and — but I didn’t. I wanted to be with my friends. I saw a group of my friends, and I got in the area they were in. So my sister wound up near the front, and I wound up about midway. When we cleared the bridge, atop the bridge I saw the policemen, and I knew we were not going to Montgomery, so I — being a warrior, I knew the procedure. I knew that we would kneel in prayer and after prayer go back to the church. I kept waiting for the front to go down. I was too far back to really hear anything that was said down front. But suddenly, we heard screams and gunshots, and we thought — I thought — what I thought were gunshots, and we thought — I thought were gunshots. And the people started screaming, and people turned, and then the police came in from behind and on the sides. We were completely surrounded. They just started beating people. People were being trampled, not only by the police and the horses, but by each other, trying to get away. It was just pandemonium. It was horrible. Blood was everywhere on the bridge. The screams is what I remember the most, you know, and the horses that were so afraid that they would rear to try to get away from the people. And these men relentlessly plowing the horses into the crowd, and the gunshots I heard turned out to be tear gas canisters exploding, and then the tear gas burning your eyes. Can’t breathe, can’t see. I mean, we panicked and couldn’t get away. People were laying everywhere. You were tripping over people that at the time your mind registered that they were dead. In fact, the last thing I remember on that bridge is seeing this lady being trampled, and I don’t know whether it’s the sound of her head or my head hitting that pavement. That’s the last thing I remember. When I awakened, I was in a car on the Selma side of the bridge in the back of a car, and my sister was in the car, and she was crying. And when I became fully awake, I realized it was not her tears falling on my face, it was her blood. She was 14 and had been beaten on the bridge and had wounds that required stitches. It was awful. I’ll never forget it as long as I live.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you end up going to jail? You were 11?

JOANNE BLAND: Yeah. We didn’t go to jail. I had gone to jail lots of times before then. We would march from the — our churches to the courthouse, and to try to get adults in and, you know, protest. Suddenly to try to stop us, they started putting us in jail. At 11 years old, I don’t remember anybody ever asking me how old I was, and I know by far I was not the youngest person there. Nobody — if you were there, you were arrested. I went to jail 13 times by the time I was 11. And that was — those are the ones we can document. Not that I remember all of them, but those are the ones I can document.

AMY GOODMAN: Joanne Bland, as we wrap up the program, and we only have a minute, your thoughts 40 years later on this 40th anniversary of the Selma march.

JOANNE BLAND: Say it again.

AMY GOODMAN: Your thoughts 40 years later —

JOANNE BLAND: It’s — I think these commemorations are important because our struggle from 40 years ago is nearly the same today. We were struggling for the right to vote. Just the right to have that right that was supposedly given. Today we are still fighting to retain that right. As we come together on this weekend and the rest of the week we have to renew that will to struggle, to keep going until all is right, to when all Americans can enjoy the freedoms afforded by the laws of this land. I think it’s very, very important. And I’m very — I’m ecstatic that so many people came, and we are not just struggling alone. It’s a lot of people out here are aware of the situation and who want to struggle to make it right. And I thank America for that.

AMY GOODMAN: Joanne Bland, I want to thank you very much for being with us, executive director of the National Voting Rights Museum, speaking to us from Selma, Alabama, on this 40th anniversary of the Selma march.

Media Options