Guests

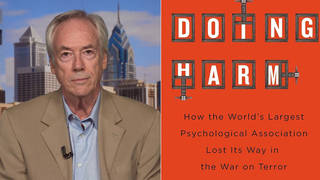

- Jean Maria Arrigomember of the 2005 APA Presidential Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security. She is a social psychologist and independent scholar. She founded the Intelligence Ethics Collection at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, and she is a founder of the International Intelligence Ethics Association.

- Dr. Nina Thomasa member of the APA Presidential Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security. She is a psychologist and psychoanalyst and is a faculty member and supervisor at New York University’s Postdoctoral Program in Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis.

- Leonard Rubensteinexecutive director of Physicians for Human Rights.

- Dr. Eric Andersformer Air Force officer who underwent SERE training. He is now working as a psychoanalyst and is starting a private practice in the East Bay this summer.

In 2005, the American Psychological Association convened a Presidential Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security that concluded psychologists’ participation in military interrogations was “consistent with the APA Code of Ethics.” It was later revealed that six of nine voting members were from the military and intelligence agencies with direct connections to interrogations at Guantanamo and elsewhere. In a Democracy Now! broadcast exclusive, we speak with two members of the task force, Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo and Dr. Nina Thomas. Arrigo says the task force report “should be annulled,” because the process was “flawed.” As an example, Arrigo says she was “told very sharply” by one of the military psychologists not to take notes during the proceedings. She later archived the entire listserv of the task force and sent it to Senate Armed Services Committee. Dr. Arrigo also calls for a “moratorium” on psychologists’ involvement in military interrogations at Guantanamo Bay. We also speak with Dr. Eric Anders, a former Air Force officer who underwent harsh training in ”SERE” (Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape) techniques, as well as Leonard Rubenstein, executive director of Physicians for Human Rights. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: The Pentagon has just declassified a report from their inspector general looking at the various investigations they conducted into repeated claims of prisoner abuse by the U.S. military. The report finds the abuse allegations “were not consistently reported, investigated or managed in an effective, systematic and timely manner.” Perhaps the most important information in the report is that it provides further documentation that psychologists played a role in the military interrogations.

In particular, the Pentagon inspector general provides concrete evidence that techniques developed by the U.S. military for withstanding torture are being used against the prisoners at Guantanamo. After 9/11, the Pentagon began using so-called behavioral science consultants, or BSCT [pronounced “biscuit”] teams, to advise the military on how to “break” prisoners to make them more cooperative.

The BSCT teams were advised by psychologists and medical staff versed in techniques employed at a Pentagon-funded program known as SERE, or Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape. SERE was created by the Air Force to teach pilots and other personnel considered at high risk of being captured by enemy forces how to withstand and resist extreme forms of abuse. The interrogation techniques devised at Guantanamo with the help of the BSCT teams eventually migrated to Abu Ghraib and other Iraqi prisons.

Last year, the Pentagon reportedly moved to only using psychologists, and not psychiatrists, to help in interrogations. Why? Because the American Psychiatric Association had adopted a new policy discouraging its members from participating in those interrogations, as did the American Medical Association. But their counterpart, the American Psychological Association, did not.

In order to justify this, the APA convened a 2005 Presidential Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security to examine the issue. After just two days of deliberations, the task force concluded, “It is consistent with the APA Code of Ethics for psychologists to serve in consultative roles to interrogation or information-gathering processes.”

When the report was released, however, it did not include a list of its members. It wasn’t until a year later that the membership was finally published in Salon.com. It revealed six of nine voting members were from the military and intelligence agencies with direct connections to the interrogations at Guantanamo and elsewhere.

Leonard Rubenstein and Dr. Nina Thomas join me now from Washington, D.C. Leonard Rubenstein is the executive director of Physicians for Human Rights. He’s been closely following this issue. Dr. Nina Thomas was a member of the 2005 APA Presidential Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security, known as the PENS Task Force. She’s a faculty member and a supervisor at New York University’s Postdoctoral Program in Psychotherapy and Psychoanalysis. Joining us on the telephone from Irvine, California, is Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo. She was also a member of that task force of the APA. Dr. Arrigo founded the Intelligence Ethics Collection at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, is a founder of the International Intelligence Ethics Association. And Dr. Eric Anders is joining us, as well by phone, former Air Force officer who underwent SERE training, now working as a psychoanalyst and starting a private practice in the East Bay this summer.

I want to go to our guest on the telephone, Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo. You and Dr. Nina Thomas were both members of this task force in 2005. Can you explain what took place behind closed doors, who was this task force, and what you concluded and debated within it?

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: I think that I would like to leave the question of who was the task force to Dr. Leonard Rubenstein and speak about what the task force concluded. I’m especially interested in the method of the task force, the process which I think was flawed. And my opinion is that because of these flaws, the task force report should actually be annulled.

But the major conclusion of the task force, from a practical perspective, was that military psychologists do have a role in interrogations and that they are obliged to follow U.S. law, rather than international law, concerning interrogations, concerning definition of torture. And since U.S. law at that time included waterboarding, for instance, as a practice that was not considered torture, contrast to international law, we were essentially permitting psychologists to participate in interrogations, at some level, OK, that involved torture. Now, there were many other high-sounding principles, OK, and platitudes, but we gave no examples, so — like the 10 Commandments, which said, “Thou shalt not kill,” but there are many exceptions done to that. I think that our other platitudes don’t have much force, because we didn’t provide any case book with examples.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me go for a moment then to Leonard Rubenstein, executive director of Physicians for Human Rights, joining us from Washington, D.C., right now. Lay out who was on this committee that Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo is now describing and Dr. Nina Thomas also was a participant in.

LEONARD RUBENSTEIN: Well, I think the most important aspect of the task force was that it was dominated by psychologists in military intelligence and from the intelligence agencies. And that fact and the fact that some of the people were actually directly involved in the use and development of SERE techniques for Guantanamo is what made the task force what it was and in some ways predetermined the outcome.

I think our concern also was the task force didn’t really come to grips with what the techniques being evaluated were. They actually didn’t discuss what techniques were used. They didn’t discuss the fact that severe humiliation, sexual humiliation, isolation, threats, all the kinds of horrors inflicted on people were really at stake, and that scientists, behavioral scientists, had somehow become implicated in torture. All that was ignored, and I think it was ignored because of the way the task force was composed, which had no interest in revealing the role they had played in the conversion of these resistance techniques into offensive interrogation techniques.

AMY GOODMAN: Stephen Soldz has a very interesting piece at Counterpunch entitled “Pentagon IG Report Details Central Role of Psychologists in Detainee Interrogations and Abuse.” And in talking about who made up the panel, he says, “Especially relevant, given the revelations in this newly released OIG, at least two of the members of this Task Force had direct SERE connections. Captain Bryce E. Lefeve had served at the Navy SERE school from 1990 to 1993 before joining the special forces and becoming the 'Joint Special Forces Task Force psychologist to Afghanistan in 2002, where he lectured to interrogators and was consulted on various interrogation techniques.' (Curiously,, he has 'lectured on Brainwashing: The Method of Forceful Interrogation.')

“But perhaps most disturbingly, on the task force was Colonel Morgan Banks. His biography states that '[h]e is the senior Army Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) Psychologist, responsible for the training and oversight of all Army SERE Psychologists, who include those involved in SERE training. He provides technical support and consultation to all Army psychologists providing interrogation support. His initial duty assignment as a psychologist was to assist in establishing the Army's first permanent SERE training program involving a simulated captivity experience.’”

And this is the group that was supposed to objectively assess the role of psychologists in interrogation and possibly abuse. Dr. Leonard Rubenstein?

LEONARD RUBENSTEIN: Yes, and I think that’s what led to the fact that it didn’t really address the key issue of the extraordinary harm that was imposed on and has been imposed on hundreds, probably thousands, of detainees in U.S. custody. There is an obligation of psychologists to do no harm. It’s no different than the obligations physicians have. And what happened, I think, is that these individuals saw themselves as behavioral scientists, not as clinicians, not subject to those kinds of ethical constraints. And the irony, of course, the paradox, is there was nothing scientific about what happened in SERE at all. There was no scientific basis for the idea that these techniques could get good information, even putting aside the fact that it amounts to torture. But there was no science behind it. So this idea that we have behavioral science teams and these were scientists helping the military do their jobs, that was kind of the veneer that the intelligence and military psychologists used to essentially justify torture.

And I should add that this is not just a historic issue. We have issues before our country now. The CIA is deciding, as we speak, what techniques it will use in interrogation. And so, this inspector general’s report is also critical to show why it is that the CIA has got to stop using the kind of techniques it has used in the past.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Leonard Rubenstein, executive director of Physicians for Human Rights; Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo, Stanford University member of the 2005 APA Presidential Task Force. When we come back, we’ll talk to Eric Anders, who went through the SERE training, and Dr. Nina Thomas, also on this panel. This is Democracy Now! We’ll be back in a minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: As we talk about the American Psychological Association and psychologists’ involvement in interrogations, are they involved with torture? We are talking with a panel of people. We go now to Dr. Eric Anders, former Air Force officer who underwent the SERE training, now working as a psychoanalyst. Explain SERE — Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape. What is this? Where did you undergo it?

DR. ERIC ANDERS: Amy, thanks for having me on the show. You did say this time SERE, which is what we used to call it when we were in the Air Force, because we were saying ”SERE” before, and I wasn’t — I want to make sure we’re talking about the same thing. And, yes, it’s Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape. And when I went through the training, it was 23 years ago, in 1983, when I went through the training. Though it’s been a long time, I remember quite a bit of it, even though I was delirious through most of it, because it was the most intense thing I’ve ever been through, and I’ve been through a lot of intense training at the Air Force Academy. And I went through it as a cadet at the Air Force Academy.

The training involves — the training is for, basically, if you’re in the Air Force, if you’re a down pilot, you need to know how to survive. You need to know how to evade the enemy, let’s say. You need to know how to resist interrogation and torture. And you need to know how to escape if you’re in a prisoner of war camp.

And also, let me say that not only did I go through the training, but I was a facilitator for one year in the training. I went through the training in between my freshman and sophomore years. You got to remember that when I went through the training I was just a child, really. I was just turned 18 — or 19, excuse me. And when I facilitated the training, I was only 20.

So, the part of the training that you seem to be focusing on for the show is the resistance part, and during that training was — let me just back up and say that during this I was delirious, not only because of the training, but I had broken my jaw before the training, and so just gotten my wires off, and so I hadn’t eaten in a long time. And so, it was a lot. It was a very difficult time. But I was, you know, having trouble sort of staying with myself during the training, because of the extreme hunger I was experiencing.

The resistance part of the training, I don’t remember how long it lasted, but the whole training itself was six weeks. And so, the resistance part was probably about ten days. We were put into a very elaborate mock POW camp, which was above the Air Force Academy’s facility in Colorado Springs.

And the training — you were hooded, brought into the training facility. I’m 6’2”. At the time, I was about 180 pounds. I was put into a very small box. I was a varsity soccer player, so I told them not to put me in the box, because it was too small for me to go into and I had knee surgeries and these kinds of things. They put me in anyway. I went into a — they put me into a larger box for the — I guess it was nighttime. It was hard to tell at the time. They would play a Rudyard Kipling poem called “Boots,” which is a very long poem, which just goes on and on and on, and anybody who knows the poem understands that it can have this — it can drive you crazy if it gets continually played on these loudspeakers. They would play Siamese music. They would play a ringing telephone, these kind of things. And during this, they wouldn’t let you sit on the ground. When we were in the big box, they would take you out, put you into stress positions. They would put you on a piece of wood on your knees and make you put your arms back in the air in this time. The whole time, they were hazing you. Something that’s important to remember, I think, is that during this training we had been through a year of basically hazing, and so we were used to being sort of abused at this time. So that was mainly what I remembered about the interrogation.

Every now and then, they’d pull you into a room and try and get out of you some information. You were given a mock assignment. You were an F-15 pilot, down behind enemy lines, and they would try to interrogate you. I don’t remember much these stress positions during the interrogation process. It was more during the other types of process. When I was a facilitator, I was a guard in the POW camp, so it doesn’t really apply as much now to what we’re talking about, because it’s the resistance part of SERE that we’re talking about. Does that answer the question?

AMY GOODMAN: Yes. And then the question of whether this is turned around — what you were being trained for, supposedly to endure abuse and torture, whether it’s training you to inflict this.

DR. ERIC ANDERS: I was recently at a psychoanalytic conference given by the Psychoanalytic Institute of Northern California in San Francisco, and on this very topic, and one of the points I made at the conference was that — you know, the reason I was at the conference was, on torture, I was disgusted by what I found out about the APA, and at the conference — I’m not a psychologist. I’m a psychoanalyst. And so, this was all pretty much news to me, though I do remember at the Air Force, at the Academy itself, there were a lot of psychologists there, or a group of psychologists, not a lot. But my point at the conference, what I made, was that I did feel that this training, in a way, is necessary.

And, you know, do I feel like we were — you know, that 19-year-olds and 20-year-olds were being prepped to be torturers? I felt that our hazing that we got for a year was probably as good a prep for teaching sort of sadistic measures as the specific training we received during the — going through. Now, the people who received quite a bit more training were the facilitators of the resistance part. I was a facilitator of the escape part. The people who facilitated the resistance part got probably pretty extensive training in interrogation. And so, I mean, but still, these are 20-year-olds, so it’s hard for me to think that they knew that they would eventually get careers as intelligence officers. It was largely a volunteer operation. So I don’t —- I mean, I didn’t see it as anything nefarious at the time. I did see it as sort of -—

AMY GOODMAN: Right, of course. You wouldn’t know what it was being used for as you were being trained in it. Let me turn to Dr. Nina Thomas, faculty at New York University, member of this APA Task Force, that only a year after the meeting did it became clear, through Mark Benjamin’s work at Salon.com, who was on this task force, that six of the nine voting members had direct ties to the military. Our guests today are two of those members who did not: Dr. Nina Thomas, as well as Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo. In this piece by Stephen Soldz at Counterpunch, it says, “In 2005, The New Yorker's Jane Mayer reported evidence that interrogators at Guantanamo were being trained in SERE techniques; they were ’reverse engineering' the resistance techniques in order to figure out how to break down detainees. While Mayer reported suspicions, direct evidence of SERE involvement at Guantanamo was lacking for another year, till, [in July 2006 _Salon_’s Mark Benjamin, in Torture Teachers reported] documentary evidence that SERE was, indeed, taught at Guantanamo. In addition to documentary evidence that SERE techniques were taught at Guantanamo, Benjamin pointed out the similarities between what is done to U.S. troops during SERE training and what was done to U.S. detainees.”

Can you talk about your discussion in this meeting and the fact that afterwards it was your panel that was used to justify, make the argument that psychologists should be a part, can continue to be a part of this?

DR. NINA THOMAS: Well, I would like to say something to correct a misunderstanding or a misrepresentation, Amy. I think you said earlier in the program that the DOD issued a statement about preferentially using psychiatrists, rather than psychologists, and it was in response to that that the task force, among other things, was established.

AMY GOODMAN: Preferentially using psychologists over psychiatrists, because the American Psychiatric and American Medical Association had tougher resolutions around this issue.

DR. NINA THOMAS: Right, right. The chronology is a little bit off, because in fact the — and I say this understanding that I am somehow at risk of representing myself as being an apologist for the APA, which I’m not, though I am proud of some of the work that’s been done. I share with Jean Maria the feeling that there were aspects of the report that were indeed flawed. But, in fact, the task force was established in response to Michael Gelles, one of the members of the task force, coming forward to raise a concern about this very issue, about the abuse of detainees both in Guantanamo and in Abu Ghraib. And it was from his whistleblowing that the impetus for the task force was established. So that’s first of all. But could you repeat your question, Amy, because I’m afraid I got lost in my own wanting to correct that?

AMY GOODMAN: Yes. I was just asking about this panel that you were on, the fact that it was used to further justify psychologists’ presence in these interrogations that many have said are so clearly abusive.

DR. NINA THOMAS: I don’t know the use to which the task force report has been put by other groups or organizations. I know there was a big brouhaha over the fact that somehow it seemed like the APA report was establishing a different set of standards or guidelines than the statements by the American Psychiatric Association or the American Medical Association. I don’t think I’m really in a position to comment about that, because I don’t know those statements, nor do I really want to take a position about those things.

As I said before, I share with Jean Maria the concern that some of the issues — for example, the question of the standard by which interrogations were going to be held, that is to say, either international standards of Geneva Conventions versus American law, and the fact that the report did not specifically address international covenants and treaties was one of the concerns that I had.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me go to Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo. You can go to your cellphone, or you could turn it off.

DR. NINA THOMAS: I’m sorry.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s OK. Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo, talk about the conditions in this panel discussion that you had, the level of confidentiality, note taking, etc.

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: Well, this is what I consider one of the very serious flaws in process. On the first morning, a person who was not a member of the panel introduced the question of confidentiality, even though there was nothing on the table at that time that merited that concern, as far as I could tell. And the chair said that we would have to establish confidentiality or our position on that before we would go on.

AMY GOODMAN: Who was the chair?

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: The chair of the panel?

AMY GOODMAN: Yes.

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: Olivia Moorehead-Slaughter.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Slaughter?

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: Yes. And so, this was actually the only issue that came to a vote, you know. And the reason given for confidentiality began with — this, again, was introduced by a non-task force member, is that we were there to kind of put out the fires, calm the waters, and that if we didn’t have a confidential process, we would essentially be fanning the flames. So that was the first reason that was introduced.

And then, one of the military people was particularly concerned about possible retaliation from terrorists to his family. And so, the military issue became conflated with the putting-out-the-fires proposal, and we had a vote at that time. I was very much opposed to confidentiality and voted against it. One other person abstained, who was concerned about the military safety issue, and all others voted for confidentiality.

AMY GOODMAN: The issue of note taking?

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: But the note-taking issue was more — hit me severely. I’m an oral historian, maybe even before a psychologist, and I always take notes. And I was told very sharply by one of the military psychologists not to take notes. No one defended my note taking. No one else, as far as I could see, was taking notes, except for an APA authority who had a computer there and took all the notes through the session and wrote our report. I don’t want to say there’s anything exactly improper in his doing that, but I think the fact that he was the only person taking notes officially was a great problem.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you continue to take notes through the discussion?

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: Pardon me?

AMY GOODMAN: Did you continue to take notes through the discussion?

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: Well, yes, but covertly, you might say. I can’t think without taking notes. After lunch on the first day, we had a first draft of our report, and almost all of our effort was going to generating a report, rather than thinking through it. And so, I took notes in the margins of these drafts as they came out. So I did take very close notes on the first half-day, and after that, notes in margins.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo, did you archive the entire listserv of the task force and send it to the Senate Armed Services Committee?

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: Yes, I did. I archived the listserv, my notes and other materials at Stanford in July 2006, and I want to add that I am not a Stanford faculty member. I simply have a relation with the archive. And on April 4th, 2007, I sent the entire listserv and my notes to the Senate Armed Service Committee.

AMY GOODMAN: And explain what the listserv is.

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: Well, the task force was in communication with each other by email before — several months before the meeting and also several months after the meeting. The meeting was in June of 2005, and this listserv, I believe, went to many people besides us whose names were then withheld.

AMY GOODMAN: Last year, we hosted a debate on the role of psychologists in military interrogations. The debate included Dr. Gerald Koocher, then the president of the American Psychological Association. This is some of what he had to say about the issue of psychologists participating in military interrogations at Guantanamo.

GERALD KOOCHER: We don’t, as a professional association, tell our members that they can’t work for a given employer. Obviously there are some people who don’t think that psychologists should assist in the military at all. That’s a political preference and a social statement, but there are many very beneficial things that psychologists have done in the military. One example is that the lead officer sent in to help clean up Guantanamo Bay was a psychologist, a U.S. Army colonel, who was sent in to help to clean up the abuses as soon as they were reported. There’s another APA member, a civilian employee at the Navy who was sent to Guantanamo and was one of the first people to file complaints with his superiors about things that he observed down there, and he reportedly brought about some changes.

I wish I had the assurance that Jane Mayer and that Dr. Reisner apparently have that there are APA members doing bad things at Guantanamo or elsewhere, because any time I have asked these journalists or other people who are making these assertions for names so that APA could investigate its members who might be allegedly involved in them, no names have ever been forthcoming.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Dr. Gerald Koocher, who was president of the American Psychological Association. Dr. Leonard Rubenstein of Physicians for Human Rights, your response?

LEONARD RUBENSTEIN: Well, I think now, from the inspector general’s report, we know and easily can identify, with the help of the APA and the military, who the psychologists were. They were at SERE. They were in the special operations directorate. They were at Guantanamo. There weren’t very many of them. It would be very easy to find out who they were.

But there’s a larger question here, too. Of course, psychologists have a role in the military, but getting them involved in interrogation tends to legitimate, not protect, people from harsh practices and from torture. The APA and the military and the CIA talk about using psychologists to make interrogation safe, as well as effective, but that’s a contradiction. What we’ve seen is that participation of psychologists tends to ratchet up the harshness of interrogations. It leads directly to torture, because it tends to validate the worst interrogation techniques. I think that’s what we saw with the behavioral science consultation teams. Even the Army surgeon general’s report on the BSCT said it was the role of psychologists to tell interrogators when to increase the pressure, how to exploit vulnerabilities.

So I think we really do have to end this as a nation, not just as professional associations. And that’s really what we’re talking about. We’re talking about ending torture. We’re ending complicity in torture by a profession that has an enormous amount to contribute to the good of humanity and should not be involved in a destruction of people.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo, the American Psychological Association will now, once again, have their annual meeting. This is a debate that is roaring through the association. People are holding back their dues because of the American Psychological Association’s position. The New York Times had a piece a while ago, about a year ago, saying that the military is turning to the American Psychological Association because of the resistance of the members of the American Psychiatric Association, the American Medical Association, to be a part of this. Are you calling for an end to psychologists’ involvement in these interrogations at Guantanamo and elsewhere?

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: Well, I think a moratorium is a good idea, until we figure out what we’re doing. Let me — I want to clarify that the American Psychological Association cannot prevent psychologists from working for the military, all right? This is, you know, a volunteer professional association. It’s the military that has said that their psychologists need to have — I don’t know, need to be licensed, and so on.

At the task force meeting itself, I heard the argument from members that psychologists were actually beneficial to the detainees in the interrogations, in keeping them safe. And I asked them, “Well, how about requiring that psychologists be present at all interrogations and be responsible for the safety?” And they rejected that idea, I mean, partly for practical reasons that there aren’t enough psychologists. But I think that that would have been an opportunity, if they actually wanted to take responsibility for the safety.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Nina Thomas, what is your opinion on this issue? And are you going to be vocal on this debate at this next annual meeting of the American Psychological Association?

DR. NINA THOMAS: Well, yes, as a matter of fact. I am going to be participating in two of the panels that have been set up by the convention programming office that address the questions involved in torture and interrogations. So I’ll be moderating one and a panelist on the other. But I feel somewhat differently from Jean Maria. I don’t know that in fact the substance of what we’re talking about is really fundamentally a difference. But I don’t feel that psychologists can be present as effectively morals monitors, because that then puts psychologists in the position whereby whatever the progress of the interrogation, the psychologist’s failure to stop procedures then becomes an implicit OK for whatever it is that’s taking place. So I would take a somewhat different stand in regard to the presence of psychologists in interrogations, as being psychologists maintaining responsibility for determining what’s OK and what isn’t.

AMY GOODMAN: And the issue of the members, your fellow members, of the committee being so intimately tied to the military and then being asked to assess the situation. For example, Colonel Morgan Banks, the senior Army Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape psychologist responsible for the training and oversight of all SERE psychologists, who include those involved in SERE training, providing technical support and consultation to all Army psychologists. Did you feel that this panel, in this panel, you were free to come to any conclusion that you felt the group needed to come to?

DR. NINA THOMAS: Well, actually, I did. Two years later — I mean, we’re talking now two years later — it’s a little bit difficult to reconstruct what the dynamics in the process were within the meetings. I don’t think I was, in fact, critically aware of what Morgan Banks’s role was at the time of the meetings themselves.

AMY GOODMAN: Isn’t that a problem, meaning the panel member, you did not know what his background was?

DR. NINA THOMAS: I knew the outline of his background, but I didn’t know the meaning of his background. So it disturbs me, yes, of course. But he was not the only participant with military background.

AMY GOODMAN: Right. Well, as, I guess, Mark Benjamin of Salon.com pointed out, when he got access to the list, six of the nine voting members, of which you and Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo, I presume, were two —

DR. NINA THOMAS: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: The other six, aside from one person, were all military-connected.

DR. NINA THOMAS: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: Jean Maria Arrigo, are you calling for a congressional investigation?

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: What would come of this, and will you be cooperating with this fully?

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: Yes, I will be cooperating with it, if asked. I’ve probably contributed most of what I can contribute. But I think that I will pass this question on to Len Rubenstein, if I might.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to come back to this discussion, and also the next guest we’re going to have on talking about the Sudan professor Mahmood Mamdani. We will save that discussion for Monday. But we’re going to continue with this, also go back to Dr. Eric Anders, former Air Force officer, went through the SERE program himself, now a psychoanalyst in the Bay Area. We’ll talk to Dr. Leonard Rubenstein about this possibility of a congressional investigation and the role of psychologists in these interrogations at Guantanamo and elsewhere. We’re talking to Dr. Nina Thomas, a member of the APA task force, as well as Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo, Dr. Eric Anders and Leonard Rubenstein. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: As we take on this issue of psychologists’ involvement with abusive interrogations, a new report coming out from the Pentagon IG office — that’s the inspector general — reporting the details of the central role of psychologists in detainee interrogations and abuse. We’re talking to two members of an APA panel, American Psychological Association, task force that convened two years ago to direct the larger American Psychological Association on the position it should take around the issue of psychologists’ involvement in torture: Dr. Nina Thomas and Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo. It is the first time they are speaking out nationally about their experiences within the panel. Dr. Eric Anders is with us, a former Air Force officer who went through that SERE program more than 20 years ago. And Dr. Leonard Rubenstein, executive director of the Physicians for Human Rights.

The significance of a congressional investigation, Dr. Rubenstein, what this would mean?

DR. LEONARD RUBENSTEIN: It would be very significant. There has been no congressional investigation into the development of torture techniques by the United States. It’s extraordinary, three years after Abu Ghraib, to have to say that, but that is the fact. And the inspector general’s report is an important impetus to have such an investigation, and it should get into the origins and use of the techniques, the use of psychologists in the development of the techniques, what is happening now, and how this can be avoided in the future. That’s the purpose of investigations. And I think it also should result in an affirmation that U.S. policy is never to use the kind of techniques that have been used, like sleep deprivation, isolation, waterboarding, all the rest of them, and that psychologists, who were very much manipulated in this process, although many agreed to participate, to be involved any longer, because their role is too problematic. They think they are trying to make it safe, but they’re making it worse. So a congressional investigation to get to the bottom of this is very important.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go now to Dr. Eric Anders once again, who went through the SERE program — again, SERE, Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape — and the question of whether there was a reverse-engineering going on, soldiers trained on how to deal with intense pressure, torture, and then the question at Guantanamo, whether that was turned around to engage in that very thing against the prisoners there. We have spoken with a number of people in the military, people like Tony Lagouranis, Anthony Lagouranis, who was in Iraq, was an interrogator, came back and said he didn’t want to be a part of what he called war crimes in Iraq. Your feeling today about what has happened to those prisoners at Guantanamo, Abu Ghraib and elsewhere?

DR. ERIC ANDERS: Well, I think it’s horrible. And I want to add to Dr. Benjamin’s point that having a psychologist in the interrogation room legitimates whatever’s happening there, with that process itself. But I think having psychologists involved with the training, with everything involved, it legitimates it, in general, or at least gives it some sort of sense of being a scientific endeavor or something like that. It’s just ridiculous. I mean, I can’t imagine — anybody who’s been through intense sort of hazing training knows that people break down, you know, regardless of whatever is used. I mean, are they doing experiments on how to make people break down? I mean, that’s not really needed. They can have experiments going on during hazing or, you know, at Parris Island in the Marine Corps.

Another thing I wanted to just add is that for any psychologists who are listening to this program, that there is a website. It’s called withholddues.com, and they can — because I do believe that the APA can have a big impact on who psychologists work for and what they do. The APA could take away the memberships of these psychologists. And I do believe that the — again, I’m not a psychologist, but the APA is involved with the licensing of psychologists. If you threaten a psychologist with their license being taken away, it would, of course, have an impact.

So I think that somebody mentioned before, you know, that psychologists should be in the room. I think assuming that psychologists are going to be this benign effect on these processes is ridiculous. That just completely disregards the history of American psychology, in terms of past experiments that have been sadistic in themselves, like the Stanford experiments, which a lot of the stuff that’s being taught — we were taught, by the way, the Stanford experiments — for those who aren’t familiar with those, they were in a mock POW camp, or a mock jail, actually, where people fell apart, became so involved with their roles, they forgot who they were. It’s called the Stanford Syndrome. So I think that it’s just kind of odd to think that the psychologists are going to be a benign effect on these processes.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, just the beginning of Mark Benjamin’s piece — this is more than a year ago, when the APA was about to have their annual meeting last year. Now, we are just before the annual meeting this year of the 150,000-member American Psychological Association, quoting the value of this panel and what came out of it, and I wanted to ask Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo this question. The panel saying psychologists participating in terror-related interrogations are fulfilling “a valuable and ethical role to a system protecting our nation, other nations and innocent civilians from harm.” That, coming out of your panel. What would you say now to the American Psychological Association, a massive organization in this country that has such an effect? What resolutions will you support in the organization, Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo?

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: If you’re referring to what the report said, I disagreed with that at the time. What often isn’t considered by critics of this report is that there was a list of recommendations, which followed this. One of the principal recommendations was a case book, and I, and I believe also another panel member, signed onto this document under a lot of pressure, but also believing that the recommendations would be carried out and that the recommendations would be corrective in some very important ways. And the fact that the recommendations have been completely dropped from this document —

AMY GOODMAN: Do you feel you’re violating the confidentiality agreement by speaking out today?

DR. JEAN MARIA ARRIGO: Do I feel that? No. I would say the reason I don’t feel that is because, as I came later to realize that the entire report had been orchestrated, I no longer felt bound by that confidentiality agreement. I thought it was inappropriate to begin with.

AMY GOODMAN: I have to leave it there. Dr. Jean Maria Arrigo, Dr. Nina Thomas, Dr. Leonard Rubenstein, Dr. Eric Anders, thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options