La Salle Parish School Board member Billy “Bulldog” Fowler reveals the school district conducted an internal investigation about the Jena Six, but the school board was not allowed to review it before they voted to uphold the expulsion of the six. The school board’s lawyer was none other than the prosecuting district attorney, Reed Walters. Asked if he felt that Walters had a conflict of interest that night, Fowler replied, “Well, I’m assuming that Mr. Walters knows the law.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Jena, Louisiana. A year ago, not many people outside Louisiana had heard of this small town, about three-and-a-half hours north of New Orleans. But a series of incidents over the past year has shot Jena to notoriety. It’s now being equated with the kind of racism many hoped was a thing of the past.

It all began at the start of the school year 2006 at a school assembly, when a student, Justin Purvis, asked if he could sit under the schoolyard tree, a privilege unofficially reserved for white students. The next morning, three nooses were hanging from its broad leafy branches. African-American students protested, gathering under the tree. Soon after, the district attorney, Reed Walters, came to the school with police, threatening, “I could end your lives with the stroke of a pen,” he said. Racial tensions mounted in this 85 percent white town of 4,000.

In December, a schoolyard fight erupted, and the district attorney charged six African-American high school students, soon to be called the Jena Six, with second-degree attempted murder. They faced a hundred years in prison each. They were immediately expelled from Jena High School.

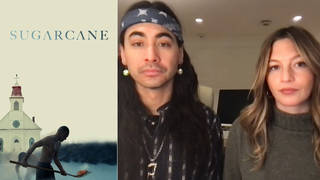

Well, I recently visited Billy “Bulldog” Fowler in his office in Jena. He’s a white member of the La Salle Parish School Board. He explained what happened when the African-American students appealed their expulsion.

BILLY FOWLER: The first meeting that I, as a school board member, sat in on was the appeal hearing of the Jena Six. We were listening — or we were told at this meeting that we couldn’t ask any probing questions about what had happened, because the charges had been filed, and it would violate some legal matter somehow. I’m not sure. And all we could do was ask the boys, “Were your rights violated in any manner?” And all we could do was vote on what we were told. And at that point, we didn’t know a whole lot, so we voted to uphold what they had done prior.

AMY GOODMAN: And that was that they should be expelled?

BILLY FOWLER: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: And you didn’t talk to the boys?

BILLY FOWLER: No. Well, we couldn’t ask them anything.

AMY GOODMAN: Because?

BILLY FOWLER: Because we were told that it would violate the law.

DAVID GOODMAN: By the district attorney?

BILLY FOWLER: Right.

DAVID GOODMAN: And the district attorney was acting in what capacity at that meeting?

BILLY FOWLER: He was acting as the lawyer for the school board.

RICK ROWLEY: Wait, I don’t think we got that on camera. So who was presiding over the meeting? That first meeting you had, who was presiding over it?

BILLY FOWLER: Well, the president of the school board presided over the meeting, but our legal authority that night was Mr. Walters.

AMY GOODMAN: And he told you you couldn’t have access to the school —

BILLY FOWLER: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: — proceedings?

BILLY FOWLER: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: Or the investigation?

BILLY FOWLER: Right. It was a violation of something. I don’t remember what he said, because at that time we were just in awe, six of us brand new on a 10-man board, and this is not how we wanted our first meeting to go, by any means.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you remember what the vote was?

BILLY FOWLER: It was unanimous. No, no, it wasn’t. There was one board member who voted no. That was Mr. Worthington.

DAVID GOODMAN: As you look at that board meeting and the situation that you had there, do you see any problems or conflicts in the roles that Mr. Walters was playing?

BILLY FOWLER: Well, I’m assuming that Mr. Walters knows the law.

Media Options