Related

Topics

Guests

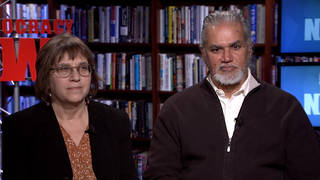

- Vic Walczaklegal director of the Pennsylvania chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. Earlier this week, the ACLU of Pennsylvania filed an amicus brief in support of the Robbins family’s lawsuit.

- Mike Walkerconsultant at the internet security firm Intrepidus Group. He blogs at Stryde Hax where he has been following this story closely.

A suburban Philadelphia school district has been accused of monitoring students at home via school-issued laptops. The webcam monitoring came to light last week after a lawsuit was filed by the family of a fifteen-year-old student who had his webcam activated after the school mistook his eating of candy for the consumption of drugs. The FBI and the US Attorney’s Office for eastern Pennsylvania have launched investigations, and a judge has ordered the monitoring to stop. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We turn now to a growing controversy. Juan?

JUAN GONZALEZ: Well, we turn now to the controversy in Pennsylvania, where a suburban Philadelphia school district has been accused of monitoring students at home via school-issued laptops.

The webcam monitoring came to light last week after a lawsuit was filed by the family of a fifteen-year-old student named Blake Robbins. According to the family lawyer, the vice principal at Harriton High School in the Lower Merion School District called Blake into her office in November and claimed she had evidence he was dealing drugs.

Attorney Mark Haltzman said, quote, “She called him into the office and told him, basically, ’I’ve been watching what was on the Web cam and saw what was in your hands. I’ve been reading what you’ve been typing, and I’m afraid you are involved in drugs and trying to sell pills.’”

According to the family, what the school mistook as drugs were Mike and Ike candies.

The school system has admitted it had the ability to secretly switch on laptop computer cameras, but officials say the cameras were only remotely activated to find missing or stolen laptops.

The FBI and the US Attorney’s Office for eastern Pennsylvania have launched investigations, and a judge has ordered the monitoring to stop.

On Wednesday, Harriton High School Vice Principal Lindy Matsko spoke out for the first time about the controversy.

LINDY MATSKO: First, as it has been previously reported, at no point in time did I have the ability to access any webcam through security tracking software. At no time have I ever monitored a student via a laptop webcam, nor have I ever authorized the monitoring of a student via security tracking webcam, either at school or within the home. And I never would. I find the allegations and implications that I have or ever would engage in such conduct to be offensive, abhorrent and outrageous.

AMY GOODMAN: Hours after Harriton High School Vice Principal Lindy Matsko spoke, the fifteen-year-old student Blake Robbins read a statement.

BLAKE ROBBINS: Nothing in Ms. Matsko’s statement is inconsistent with what we stated in our complaint. Ms. Matsko does not deny that she saw the webcam picture and screen shot of me in my home. She only denies that she is the one who activated the webcam. The issue is that we know someone accessed my webcam and provided Ms. Matsko with a screen shot and a webcam picture of me at my home in my bedroom.

AMY GOODMAN: To talk more about the webcam monitoring, we’re joined by two guests.

Vic Walczak is legal director of the Pennsylvania chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. Earlier this week, the ACLU of Pennsylvania filed an amicus brief in support of the Robbins family lawsuit.

We’re also joined by Mike Walker. He’s a consultant at the internet security firm Intrepidus Group. He blogs at StrydeHax.blogspot.com, where he’s been following this story closely.

Well, let’s begin with Vic Walczak of the ACLU. Explain exactly what happened to Blake.

VIC WALCZAK: Well, I guess I’m not the best person to explain that, because I don’t know. Just to be clear, the ACLU is not representing the Robbins family.

Based on the allegations in the complaint, apparently the school district remotely accessed Blake’s school-issued laptop computer while he had it in his room. And I guess there’s a couple of things that are claimed the school district did. One is that they viewed Blake through the webcam in his room. And the second is that they took screen shots of what it is he had up on his computer screen. And both of those are just — if you think about, the school is coming into the students’ and the parents’ home, and if they don’t have an invitation, if they don’t have a search warrant issued upon probable cause by a judge, it is a clear privacy invasion under the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution.

AMY GOODMAN: The school gave out 2,300 Apple computers, right? To all the kids.

VIC WALCZAK: That’s our understanding, yes.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Now, this happens in Lower Merion. I’m familiar with that area. We’re talking about the main line of the Philadelphia suburbs, probably the wealthiest area in all of southeastern Pennsylvania. What’s been the reaction among people in that community and in the press to this?

VIC WALCZAK: I’m sorry, are you asking me?

JUAN GONZALEZ: Yes.

VIC WALCZAK: Yeah, I’m in Pittsburgh, but based on what I’m hearing from my colleagues in Philadelphia is there really has been a firestorm of criticism. And the school district has acknowledged remotely accessing students’ computers. Apparently they claim they‘ve done it forty-two times. And their explanation is that they used it as an anti-theft device, but — and maybe I just don’t fully understand the school district’s explanation, but consider me a skeptic. How is it that a webcam is going to be able to prevent or retrieve a computer that’s been stolen? If the computer is not turned on, the webcam is not going to work. If it is turned on and you manage to take a snapshot and see some stranger sitting in front of it, how’s that going to help you retrieve the computer? If you really want to use this as an anti-theft or a locating device, you put a little computer chip on it, and then you can track where it is. That would be a whole lot more effective, and many computers already have that kind of technology.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s go to Mike Walker, talking about this technology, consultant at Intrepidus Group, blogging at Stryde Hax. How did the school do this? I mean, do Apple computers have to participate in this to allow the school to put something into this computer that would allow them to secretly turn on these webcams, Mike?

MIKE WALKER: Good morning, Amy.

I hadn’t heard that statement from the principal. That’s very interesting.

To answer your question, yes, they had to install software. It didn’t come from Apple. It came from a third-party vendor. And it was remote administration software. Remote administration software has a lot of tasks for allowing administrators to exert control over student laptops. And most of the time, that’s very benign control. But this remote administration software had some features labeled in the software’s computer tracking, addressed by the high school staff as “theft-tracking,” for remote activation of taking pictures of the screen while it was in use and for remotely activating the webcam.

I’m certain that the technology is in the software to remotely activate the webcam. And there’s very compelling evidence posted on the internet by administrators at the school, technical administrators, that they were using this technology. How they were using the technology remains a matter of debate.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Well, I want to turn now to a school official from the Lower Merion District explaining how the tracking program worked. Michael Perbix, a network technician at the school district, spoke about the system in a webcast for the company LANrev that was archived on the internet.

MICHAEL PERBIX: Hello, my name is Michael Perbix. I am a network technician at Lower Merion School District, right outside of Philadelphia.

When you enable tracking of a computer, what actually happens is you make your LANrev server available to the internet over whatever port you have configured. And as soon as the computer gets put on a network outside your home network, the heartbeat tries to come into your existing LANrev server. And once it establishes that connection, it gets told, hey, computer tracking is turned on. And then that computer will start sending back, at regular intervals, will start sending back screen shots. And if you have a built-in iSight camera, it will start sending in camera shots.

So you can see here my lovely house that I took — the laptop was sitting on my living room table, and on the screen you’ll see I had a Word document open there. This is a test of how this works from home. And if you look at the top, even though I blurred it out, you can see that you have the information. You have the track time. You have the tracked computer public address, which would be the network address of the house or organization where that information is coming from. And then you have the full tracked computer resolve, the DNS name. And that DNS name right there can be used by local police to get a warrant to query Verizon, or whoever, to find out who had that DNS name at the times that are indicated there, which will help the police try to track down your stolen laptop. So, it’s an excellent feature.

Yes, we have used it, and yes, it has gleaned some results for us. But it, in and of itself, is just a fantastic feature for trying to — especially when you’re in a school environment and you have a lot of laptops and you’re worried about, you know, laptops getting up and missing. I’ve actually had some laptops we thought were stolen, which actually were still in a classroom, because they were misplaced, and by the time we found out they were back, I had to turn the tracking off. And I had, you know, a good twenty snapshots of the teacher and students using the machines in the classroom.

But you’ll see that the feature works fantastic. And the key is having your LANrev server accessible to the outside world, so that the screen — so that the heartbeats can come in and the information can come in.

AMY GOODMAN: Mike Walker, your response? That was the school official explaining how fantastic their software is.

MIKE WALKER: Well, I said there was very compelling evidence that they were using it. That’s the evidence. And it’s exactly like he described. When a computer wasn’t checking in, when it was reported stolen or missing or they didn’t know where it was, they could schedule commands for the computer to pick up the next time it checked in. So when it checked in, if it came — if it checked into the school’s central server and there were commands waiting for it to start taking pictures, it would start taking pictures.

And what’s really interesting about that story that he just related is mistakes happen. They didn’t know where these computers were. And it’s important for people to understand, when these computers were activated, if they were reported missing, it would start taking pictures wherever they woke up. Even if they were stolen and they were in the bedroom of a kid who stole it, they were going to start taking pictures the moment they woke up. And after that search was conducted, then when the administration looked at the pictures, they were going to be able to find out whether that search was appropriate or not.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Well, Mike Walker, don’t you think that, given these features and this software that’s installed in these computers, that the school district had a responsibility to alert the parents of these students, at minimum, to say, “Hey, we’re giving you these computers, but you should know that these computers have these kind of features,” and then the parents could decide whether they wanted to accept them on that basis?

MIKE WALKER: I think they had a responsibility to inform. And my personal opinion on the subject is, is I think they had a responsibility not to build the feature into the software at all, or to deploy software that did this, because the purpose of theft-tracking, of finding a computer and finding out who’s using it, can be fulfilled utterly by taking pictures of what’s being done on the screen and by the remote IP address tracking functionality that’s already in the computer. There are several highly effective computer-loss tracking mechanisms, like Computrace, that work that way that don’t take pictures. I think that’s a big leap in technology and one that shouldn’t have been made.

AMY GOODMAN: Mike, you cover your camera on your computer?

MIKE WALKER: I’ve had tape over my webcam since I bought my computer. And almost everyone I know that I work with does the same thing.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, Vic Walczak, very quickly, what you’re calling for right now?

VIC WALCZAK: Well, the ACLU’s interest was in making sure that the school district stopped this remote access. And this is equivalent of a principal sneaking into a kid’s bedroom closet and peeking out whenever he or she wanted. It’s hard for me to imagine that any parent would agree to this.

Fortunately, on Monday, the court issued an order, that the school district agreed to, which makes it clear that they cannot continue this kind of surveillance, this remote surveillance. And if they do, they’re subject to the court’s contempt powers.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you both for being with us. Vic Walczak, legal director of the Pennsylvania chapter of the ACLU, and Mike Walker, consultant at the security firm Intrepidus Group, blogging at Stryde Hax.

This is Democracy Now!

When we come back, we’ll speak with Shane Harris, author of The Watchers: The Rise of America’s Surveillance State. Stay with us.

Media Options