Guests

- Gareth Peirceone of Britain’s best-known human rights attorneys. She has represented numerous prisoners held at the U.S. military base at Guantánamo Bay, as well as WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. She is author of Dispatches from the Dark Side: On Torture and the Death of Justice.

- Tamer Mehannathe brother of U.S. terror suspect Tarek Mehanna, who has been held in pre-trial 23-hour solitary confinement since October 21, 2009.

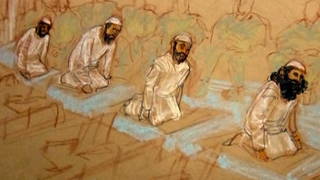

Ten years after the 9/11 attacks, detention policies in the United States are facing increasing scrutiny both here and abroad. American citizen Tarek Mehanna is set to stand trial this month on charges of “conspiring to support terrorism” and “providing material support to terrorists.” Mehanna is accused of trying to serve in al-Qaeda’s “media wing.” He was 27 years old when he was arrested in October 2009 and has been held in solitary confinement since then. Mehanna was originally courted by the FBI to become an informant. Meanwhile, the European Court of Human Rights is hearing a case on the legality of extradition of terror suspects to the United States on the grounds that inmates are subjected to inhumane conditions of confinement and routine violations of due process. This could become a landmark case in human rights law, potentially damaging the international reputation of the U.S. legal system. To discuss detention policies since 9/11 in the United States, we’re joined by Tarek Mehanna’s brother, Tamer, and Gareth Peirce, one of Britain’s best-known human rights attorneys. She’s represented numerous prisoners held at the U.S. military base at Guantánamo Bay, as well as WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

JUAN GONZALEZ: Ten years after 9/11, detention policies in the U.S. are facing increasing scrutiny both here and abroad. A terrorism trial set to begin later this month is already attracting international attention. American citizen Tarek Mehanna is set to face charges of “conspiring to support terrorism” and “providing material support to terrorists.” Mehanna is accused of trying to serve in al-Qaeda’s media wing. He was 27 years old when he was arrested on October 21st, 2009, and has been held in solitary confinement since then. Mehanna was originally courted by the FBI to become an informant. After refusing, he was arrested in 2008 for issuing a “false statement” to a federal officer. He was released on bail of a million dollars, only to be arrested again in 2009 on material support charges and denied bail. He faces a life sentence when his trial begins in Boston on October 24th.

AMY GOODMAN: In a moment, we will go to the brother as well as a leading human rights attorney in Britain. We are going to be speaking with Gareth Peirce, but we’re going to break first. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: The European Court of Human Rights is hearing a case on the legality of extradition of terror suspects to the United States on the grounds that prisoners are subjected to inhumane conditions of confinement and routine violations of due process. This, becoming a landmark case in human rights law, potentially damaging the international reputation of the U.S. legal system.

To talk more about U.S. detention policies since 9/11, we’re joined by Tarek Mehanna’s brother, Tamer Mehanna. Also in our New York studio, Gareth Peirce, one of Britain’s best-known human rights attorneys. She has represented numerous Guantánamo prisoners. She also represents WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. And she has a new book out, which is called Dispatches from the Dark Side: On Torture and the Death of Justice.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Gareth Peirce, in the United States because she came to a symposium at Brooklyn College on the issue of how the U.S. deals with the so-called war on terror. Tarek Mehanna set to face charges of conspiring to support terrorism and providing material support to terrorists. We’re joined right now, as I said, by his brother. If you could talk about Tarek’s case—what happened? Who is your brother?

TAMER MEHANNA: Well, my brother and I grew up with our parents in Sudbury, Massachusetts, an affluent town. We lived a very normal life, like most American teens, with normal hobbies: comic book collecting, rock-and-roll music—my brother actually inspired my taste in music—drawing—Tarek was a really artistic—really, really talented artist growing up. You know, I remember, like, a lot of, you know, his work, you could fit it into Marvel Comics, easily. Again, you know, normal childhood hobbies.

And around the time when Tarek was graduating from high school, his thoughts on faith and identity really began to mature a bit. And I think that was as a result of certain really powerful classes that he took at Lincoln-Sudbury High School, which is where we graduated from, like a cultural anthropology class, in particular, really had an impact on him and made him—it really expanded his worldview and made him think more about, you know, the similarities and differences between peoples.

And as a result of the maturing of his faith, he really became a much more active member of his community, particularly in the Worcester community. He was really well known in a lot of the different communities, because he would be invited to give Friday sermons, because we go—as Muslims, we congregate in prayer on Fridays each week. And so, he was well known at all of the local mosques in the Boston area. But the main one that he really invested heavily in was the Worcester community, because it was a strong and cohesive community, and Tarek really felt strongly that, as a member of a community, you should give back to it as much as you can.

Now, me and Tarek both graduated from pharmacy school in Massachusetts, College of Pharmacy. We’re both pharmacists. Tarek decided to forgo a six-figure salary in order to, again, you know, give back to his community as a teacher, you know, because the mosque has—associated with an academy. And he used to teach children there in science and math and history and religion.

In addition, Tarek runs a blog called iskandrani.wordpress.com. If you visit it, you see that it’s really—it’s a resource meant to make available to Muslim converts and to non-Muslims a number of primary texts, primary sources, pertaining to Islam, many of them published by ancient scholars in Arabic. And Tarek really dedicated a lot of his time to translating these texts to English, because, you know, they really help to add insight to what Islam is really about, in a way that a lot of sources today are more biased about. And so, Tarek always felt strongly that if you want to know about something, then you really need to study it, and you need to go to—you know, you need to go to the roots of it. And so, he made those available on his website.

And he translated a variety of texts, maybe 30, 40 titles. And the government—the charges that he was arrested on ultimately in 2009 was that one of these texts related to a book called The 39 Ways of Jihad. And I suppose, you know, there’s two ways that you could look at it. You could look at it, on the one hand, as, you know, it would be different if, let’s say, you have an individual who that was the only book that he translated. And it’s a very different story when you have an individual who has translated upwards of 30 or more texts, and that’s one of them, and when these texts deal with a broad variety of topics.

JUAN GONZALEZ: The government also claimed, supposedly, that he attempted to get training at some point as a jihadist fighter.

TAMER MEHANNA: Right.

JUAN GONZALEZ: That’s part of their claims.

TAMER MEHANNA: That he traveled to Yemen in order to do this. Now, the interesting thing is that when asked by the defense whether or not the government was aware of any training camps in Yemen at the time, the prosecution, presumably after looking into it and realizing that there was—there were no documented camps in Yemen at the time, responded that it doesn’t matter whether or not the government suspected that there were any camps at the time. It’s very odd, because it’s—why would you presume that that’s why he went there if there’s no evidence that there were any camps there in the first place? It’s just one of a number of very, very bizarre positions that the government is taking.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, we don’t have much time, but talk about his first imprisonment and then his second imprisonment.

TAMER MEHANNA: His first imprisonment was in—he was arrested in October of 2008. And it came after approximately a six- to seven-month period of intense FBI pressure on him. What had happened was that, between 2005 and 2008, the FBI had placed considerable pressure on him to become an informant, because he was so involved in his communities. He was an ideal informant, because he was well trusted. Everybody knew him very well. And Tarek has a very distinctive character and very strong principles, uncommonly strong principles. So he was known to be very honest and a very sincere person. So, let’s say, if Tarek was to act as an informant, let’s say, as a cooperating witness in the case of somebody, then he would present a very believable testimony.

JUAN GONZALEZ: Well, Gareth Peirce, I’d like to ask you, he has been now—his brother has been in solitary confinement, basically, since his arrest, 23 hours a day. This whole issue, as you’ve been raising, about the imprisonment policies here in the United States and how it relates to the general sense around the world, especially in the industrialized, advanced countries, about treatment of prisoners?

GARETH PEIRCE: Well, you might say it’s not our business, looking at it from the U.K., but it’s become our business because the U.S. has been attempting for some years to extradite a number of men from the U.K. on charges similar to that, very vague allegations of providing material support. But if here they would be confined—and this is agreed by the U.S. government—confined in complete solitary confinement, pretrial, for up to three years, enabling them not at all to do justice to their case at trial, they’d be broken men by the time they came to trial, in utter isolation. It cripples a human being.

But after trial, if convicted, they would face confinement in extreme, severe isolation in a supermax prison. And looking at it from the outside, we have been shocked and troubled at the extent to which men—perhaps women, too, I don’t know—imprisoned in the United States, some 20,000 prisoners, in extreme isolation, potentially for life, many of them serving sentences of life without parole.

Now, the point, the legal point, is this, where we’ve got to: the European Court on Human Rights has prevented those extraditions, and they will stop, and never happen, unless the court can be persuaded this does not violate the prohibition on torture and inhuman treatment. At the moment, the cases have achieved admissibility and permission, that they have a strongly arguable case that this will be prohibited in any European country. And that’s why it’s become a mutual issue for our two countries.

AMY GOODMAN: Tamer, describe your brother now. How long has he been in solitary confinement? Where is he? And what is happening to him? Have you spoken to him?

TAMER MEHANNA: Yes, my brother has been in solitary confinement for—going on two years now, two years of his life that he’ll never get back.

AMY GOODMAN: How old is he?

TAMER MEHANNA: He’s 29. He just turned 29 yesterday.

AMY GOODMAN: Where is he?

TAMER MEHANNA: He’s being held at Plymouth County Correction Facility in Massachusetts.

AMY GOODMAN: When did you last see him?

TAMER MEHANNA: And I last saw him about two weeks ago. We’re allowed to see Tarek two—two days a week. He has a list of five visitors he’s allowed to see. Two people are allowed to go up each day. But I’d like to point out that Tarek’s condition is not typical of most prisoners. Most prisoners break down over that period of solitary confinement. But Tarek, again, because he’s a very strong-willed individual, he has been resilient. He’s been resilient, and we are confident that he’ll continue to be so, as we wait.

AMY GOODMAN: When will he be tried?

TAMER MEHANNA: His trial begins October 24th, which is roughly a week and a half or so from now. And jury selection begins the 24th, and the trial is slated to begin the 26th.

AMY GOODMAN: Gareth Peirce, how often do you deal with cases like this?

GARETH PEIRCE: Often—too often. In the last 10 years, both in the U.K. and the U.S., the allegation—allegations have extended themselves so that they become infinite and indefinite. How could a person who translates a document into English, by that alone, be regarded as providing material support? It destroys entirely the concept of freedom of expression. But on top of that, to be put in circumstances where you are, at best, crippled in defending yourself has to be wrong. And the punitive element, that you ought to be crushed as a human being for doing so, goes against all our ethos of what we should stand for.

But the conference yesterday embodied a collection of families and those relatively few lawyers who are aware of this, who are sharing what’s a hidden experience. And I think one of the things to look at, the protests in the park. They were providing inspiration yesterday to a group of people who felt there was no hope. And they were collectively saying, it is time we told this. It is time. It’s a hidden disgrace in America, the use of solitary confinement, the extension of sentences, the crippling of communities. And so, it’s an important moment of time, I think, to be raising those issues. And we thank you for raising them on your program.

JUAN GONZALEZ: And the argument of the government, especially in a material support situation like this, for keeping someone in solitary confinement for 23 hours a day?

GARETH PEIRCE: Well, you have an interesting statistic, which is, 97 percent of accused people in this country plead guilty. And they no doubt do that to avoid the enormity of the consequences if they don’t. And that, itself, is used as a device to achieve cooperating witnesses. It’s a form of pressure that’s punitive but is a very serious attempt to achieve a result. And it often, more often than not, does.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you for being with us, Gareth Peirce and also Tamer Mehanna, brother of Tarek Mehanna, who goes to trial later this month. We will continue our conversation offline, and we’ll post it at democracynow.org.

Media Options