Guests

- Michael PollanKnight Professor of Science and Environmental Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Journalism. He’s written several books about food, including The Botany of Desire, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto, Food Rules: An Eater’s Manual, and the forthcoming Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation.

As California voters prepare to vote on whether to label GMOs in food, we go to Berkeley to discuss Prop 37 and its implications for the broader food system with journalist and best-selling author Michael Pollan. Among the nation’s leading writers and thinkers on food and food policy, Pollan is the Knight Professor of Science and Environmental Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Journalism. He’s written several books about food, including “The Botany of Desire,” “The Omnivore’s Dilemma,” “In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto,” “Food Rules: An Eater’s Manual,” and the forthcoming “Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

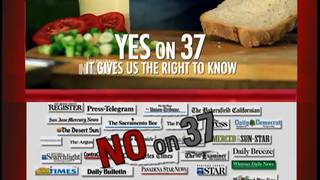

AMY GOODMAN: We’re broadcasting from Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, as we continue our discussion now about California’s Proposition 37, which would require the Department of Public Health here in California to label genetically engineered food. If Californians vote yes on Prop 37 on November 6, California will become the first in the country to require such a labeling system, possibly creating ripple effects across the nation.

We are going right now to Michael Pollan. Michael Pollan is a professor of journalism at the University of California, Berkeley’s School of Journalism, in the studios at University of California School of Journalism.

We thank you very much for joining us, Michael. Michael has written a number of best-selling books, leading writer and thinker on food and food policy. He is the Knight Professor of Science and Environmental Journalism at UC Berkeley School of Journalism. Among his books, The Botany of Desire, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto and Food Rules: An Eater’s Manual. His next book will be called Cooked: A Natural History of Transformation, which is due out next year.

Michael Pollan, welcome to Democracy Now!

MICHAEL POLLAN: Thank you, Amy.

AMY GOODMAN: As you hear this debate that we just had on—on Prop 37—

MICHAEL POLLAN: Not every minute of it.

AMY GOODMAN: —your thoughts?

MICHAEL POLLAN: Not every minute of it. Look, I think this is a—it’s easy to get lost in the weeds about this thing, because there’s been a lot of charges and countercharges flying around. But I actually think this is—there’s a lot of stake here, and not just for Californians.

You know, we have—genetic modification was a major innovation in our food supply that we have not had a chance to debate in this country. And it goes back now 'til 1996, when these first crops were introduced. And unlike in Europe, where there was a pretty heated debate, and in Japan, in a resolution that involved labeling—they're sold in these places, most of them, but they’re labeled—we never had that debate, because both political parties agreed, and when in America both political parties agree, there’s no space for politics. And so, I just think it’s—it’s that opportunity for us to start talking about it.

And if this label passes in California, there will be enormous pressure for a national label by the food industry, among others. If it survives court challenges—because, make no mistake, if it passes, Monsanto will take it to court on the very first day—there will be pressure, because food companies will not want to make—formulate food differently for California than the rest of the country. So we’ll have that national debate over whether to label this product or not. And I think that’s a—that’s a healthy thing. How can that not be healthy?

AMY GOODMAN: Well, talk about who are the forces that are behind this, and put it in a context. You’ve been writing about food now for decades. Put it in the context of what you talk about as the food movement in this country.

MICHAEL POLLAN: Well, something—something very exciting is happening around food in this country. There is a movement. It has—you see it when you go to the farmers’ market. You see it in the kind of conversation we’re having about food in the media. People are getting very interested in where their food comes from, how it was produced, and they’re trying very hard to, you know, vote with their fork, as the slogan goes, for the kind of food that supports their values, the kind of food that they deem most healthy or environmentally sustainable.

And this movement is a tremendous threat to big food, which would much rather we didn’t think about how our food is produced, because it’s often not a very pretty picture. I mean, take the meat industry, for example. They don’t want you to think CAFO, feedlot, factory farm, when you pick up a piece of beef; they want you to think home on the range, cowboys, you know, a 10-gallon hat. So, there’s a real disconnect between the way food is being sold to us and the way it’s actually being produced.

And genetic modification is part of that disconnect. It is—there is a story about how this food is produced that the industry would rather you not know. They’re happy to talk to, you know, editorial boards in op-ed pages and the elites at conferences about feeding the world, and this is the only way we can feed the world and drive up yields and save the forest, but for some reason they don’t want to have that conversation with consumers, the people who actually have to eat the stuff.

And the reason for that is quite simple. Consumers would probably avoid genetically modified food if they were given the choice. At least that’s the fear of the industry. Now, why would they do that? The industry likes to depict that as irrational behavior, you know, this fear of the unknown or of this new technology. But, in fact, it’s perfectly rational to avoid genetically modified food, so far. And the reason is, as Stacy said earlier, it offers the consumer nothing. It may or may not offer farmers some edge in terms of convenience, but to the consumer, all it offers is some uncertainty, the doubts that have been raised by certain studies about it, and also a type of agriculture that some consumers want to avoid: giant monocultures, you know, under a steady rain of herbicides, which is what most GM crops are. So, faced with that risk-benefit analysis, some undetermined possible risk versus no benefit whatsoever, what’s the smart thing to do? Smart thing to do is just avoid it until we know more about it.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the forces that you’ve come up against in your many books, as well, and in speaking around the country, that are behind. I mean, what Dr. Zilberman was just saying is that people like to make it sound like this is a corporate movement, but he says it is not, the movement against Prop 37.

MICHAEL POLLAN: Well, you know, genetically modified organisms may have been developed in laboratories by scientists in places like Berkeley, but make no mistake, they’re owned by very large corporations. Monsanto and DuPont now own something like 47 percent of the seed supply in this country. The real benefit of GM to these companies is really the ability to control the genetic resources on which humankind depends. It is like putting a bar code on every plant. You can tell if it’s your plant in the field. And you—farmers are forced to sign contracts forbidding them from saving seed and forbidding researchers, by the way, from studying these crops.

So—and this is perhaps my biggest objection to the technology. I’m not persuaded there is a health threat attached to GM; I think we still need to do a lot more work on that question. But what I know and don’t need to be persuaded of is that this represents a whole new level of corporate control over our food supply, that a handful of companies are owning the seeds, controlling the farmers and controlling our choices. And the food movement is all about diversity. The food movement is all about consumers connecting directly with farmers and cutting out that narrow waist of the hourglass that all our food has been passing through, these monopolies and oligopolies.

And, you know—and the consumer desires something else. But the consumer needs knowledge in order to make good choices. And there are a certain number of people who would simply like to avoid this kind of food. David Zilberman was saying that, well, you can avoid it by buying organic, but organic is expensive. And there are people who want to avoid it who can’t afford organic. We shouldn’t just make—we can’t have a two-class food system where people who want to avoid GM and buy sustainable, humanely raised meat, they get to have this good food, and everybody else is stuck with this industrial crap because they can’t afford anything better. I think we need to democratize the ability to choose good food. And this is—this is a way to do that.

AMY GOODMAN: Michael Pollan, I want to ask you about President Obama’s record on reforming the U.S. food system. Less than two weeks before he won the 2008 presidential election, President Obama told Joe Klein at Time magazine, quote, “I was just reading an article in the New York Times by Michael Pollan about food and the fact that our entire agricultural system is built on cheap oil. As a consequence, our agriculture sector actually is contributing more greenhouse gases than our transportation sector. And in the meantime, it’s creating monocultures that are vulnerable to national security threats, are now vulnerable to sky-high food prices or crashes in food prices, huge swings in commodity prices, and are partly responsible for the explosion in our healthcare costs because they’re contributing to type 2 diabetes, stroke and heart disease, obesity, all the things that are driving our huge explosion in healthcare costs.”

MICHAEL POLLAN: Ah, God, he really kind of got it, didn’t he? I mean, look, Obama understands the problems of the food system. He can connect the dots between the way we’re growing food in these huge monocultures to overuse of fossil fuels to grow those crops, and production of lots of unhealthy food that leads to the healthcare crisis. Environment, energy, health—they’re all linked to the food system. And you’re not going to really make progress on any of those three issues without addressing the way we’re growing food.

Obama understands this very well, but he also understands political reality. And to move against this system in any significant way will spark an enormous backlash. The food industry is one of the most powerful, if not the most powerful, industries in Washington. Witness, you know, the debate over the farm bill. Witness the debate over antibiotics in livestock. There are many very commonsense provisions that simply don’t stand a chance in Washington. And Obama made a calculation early on that he did not have enough support behind him to move against this system and try to reform it. And, in fact, he has said this to people.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, it’s interesting. Let’s—let’s go to what he said in 2007 when he was running for president, promising to label GMO foods, if elected.

SEN. BARACK OBAMA: Here’s what I’ll do as president. I’ll immediately implement country-of-origin labeling, because Americans should know where their food comes from. We’ll let folks know whether their food has been genetically modified, because Americans should know what they’re buying.

AMY GOODMAN: That was President Obama before he was president. Michael Pollan?

MICHAEL POLLAN: Yeah, so he kind of pre-endorsed Proposition 37. And—but, you know, since he’s come in, most of his decisions have taken the side of Monsanto. Most of his decisions have taken the side of industrial agriculture against people seeking, say, to break up the big monopolies in meat packing.

And the reason he’s done this is he’s a good student of politics: he understands there’s not yet enough political support, that this movement I’m describing is a very young movement. It is—you know, if you compare it to the environmental movement, it’s pre-Earth Day. It’s—it hasn’t yet had that galvanizing national political movement. People so far are voting with their forks, and we are, from the grassroots, creating an alternative food economy—very important, very powerful and incredibly exciting to watch. But this movement hasn’t yet exerted any muscle at the ballot box, in Congress, in the White House.

And that’s why this is such an important vote, because if this passes—and let us assume that Obama is re-elected—he will see there are votes in reforming the food supply. That’s why this is not just a California issue. This is a national issue. This is the first time for the food movement to pass from that moment of voting with your fork to voting with your votes for a different kind of food system. And that’s why I’ve devoted a lot of energy to writing about this and talking about it, because I think there is a lot at stake.

Obama can be moved on this issue. He has told people, you know, “Make me do it.” And it’s up to us to make him do it, because he does get it. That’s one of the reasons his wife, Michelle Obama, is out there speaking about food. I think she’s building support for the kind of movement we’re talking about, by elevating the conversation about food and making the links between the way we shop, the way we eat and our health. But I think Obama simply judged the politics were not ripe yet. Well, this will ripen them dramatically, should this pass.

AMY GOODMAN: We have to break. We’re going to come back and discuss soda bans and soda taxes and more. We’re speaking with journalist and author Michael Pollan. Stay with us.

Media Options