Guests

- Mohammed El-KurdPalestinian journalist, Palestine correspondent at The Nation and an editor-at-large at Mondoweiss.

In Part 2 of our interview with the acclaimed Palestinian writer Mohammed El-Kurd, he talks in depth about stories from his new book, Perfect Victims, including about the beloved poet, academic and activist Refaat Alareer, who has finally been laid to rest, more than one year after he was killed in an Israeli strike in Gaza along with his sister, brother and four nephews. His family recovered their remains after a neighbor buried them in a yard at the site of the Israeli attack. Alareer was buried in a cemetery in Gaza City’s Shuja’iyya neighborhood, where Alareer was born.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we continue with Part 2 with our conversation with Mohammed El-Kurd, Palestinian journalist, whose new book is out today. It’s titled Perfect Victims: And the Politics of Appeal. He’s an editor-at-large at Mondoweiss and the first Palestine correspondent at The Nation magazine.

I want to ask you about the poet, beloved academic, activist Refaat Alareer, who has finally been laid to rest more than a year after he was killed in an Israeli airstrike, along with his brother, his sister and his four nephews. His family recovered their remains after a neighbor buried them in a yard at the site of the Israeli attack. Refaat was buried in a cemetery in Gaza City’s Shuja’iyya neighborhood, where Refaat was born. He appeared on Democracy Now! several times.

REFAAT ALAREER: The only hope we have is in the growing popular support in America, in the movements of — the movements, the human rights and the rights movements in America and across Europe, to take to the streets to pressure their politicians into putting an end to this dark, dark episode of not only the history of the Middle East, but also the history of humanity. If people are asking how was the Holocaust allowed and other genocides in Africa and across the world, now you can see this live on TV, live on social media. Palestinians’ whole blocks destroyed, hospitals, schools, businesses. We are speaking about thousands and thousands of housing units destroyed by Israel. So, my message to the free people of the world is to move to pressure, to mobilize and to take to the streets.

AMY GOODMAN: Those were the words of Refaat Alareer on Democracy Now!, October 10th, 2023. He was killed two months later. After his death, the actor Brian Cox recited Refaat Alareer’s poem, “If I Must Die.”

BRIAN COX: If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze—

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself—

sees the kite, my kite you made, flying up

above

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale.

AMY GOODMAN: Brian Cox reciting Refaat Alareer’s poem, “If I Must Die.”

I remember it, while we were in Dubai at the U.N. climate summit, when we learned. Talk about, Mohammed, where you were. You begin your book with a dedication. I want to ask you about who Omar is, but also in loving memory of Dr. Refaat Alareer. Where were you the day you learned he died?

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: I was in my apartment in New York, and I was en route to go to the airport to go to London. And it was quite the shock to hear that.

AMY GOODMAN: You had been communicating with him in the weeks before?

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Yeah, yeah, we’ve been in constant communication. And there are just people who you can only think about in the present tense, and it’s hard to think that they would pass, and he was one of them. I don’t want to — I don’t want to talk about, you know, him as though he was infallible, but he really did not mince words. It was just, he was — he was not my personal teacher, but he always felt like a teacher, just watching how he utilized humor, how he’s — and, you know, there’s dozens, if not hundreds, of his students that speak for him.

AMY GOODMAN: He had already — his home was bombed —

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: — when you were texting with him.

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: So, he had just left his home?

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Yeah, yeah, he did. And he sent me — you know, it’s almost hard to talk about, but he sent me a message, a very, very sweet message, saying that the only two things that he took from his home was a copy of his anthology, Gaza Writes Back, and a copy of my poetry book. And it was — it was very — it was a very profound message to receive from such a giant, you know? Yeah, it meant a lot to me.

AMY GOODMAN: So, he was talking about your book Rifqa, which —

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: — you began as a teenager —

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: — a collection of poetry, named for your grandmother. Before we continue talking about Perfect Victims, talk about your grandmother.

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: You know, I like — you know, I like to say that my grandmother was an icon of resilience, in the sense that she lived through the British Mandate, she lived through the Israeli, you know, occupation of '48 lands and then ’67 lands, and then she lived through First Intifada, Second Intifada, and then our house being taken once and twice, you know, and being threatened with expulsion in Sheikh Jarrah. And she was very, very, very — she was a very stubborn woman. People like to say — people like to say defiant. I think that's also true about her, but she was also very, very stubborn. And she always — she loved to call things by their names.

And she was just emblematic of Palestinian women at large. You know, they’re largely erased. We often talk about women and children being the people who bear the brunt of war, which is true, but oftentimes in that framing, we kind of erase the contributions that women have contributed to the anti-colonial struggle. Palestinian women have played vital roles in the First Intifada and the Second Intifada, in the Unity Uprising in 2021 and today, you know, and they’re often disregarded.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, you talk a lot in Perfect Victims, and that’s implied in the title itself, about the framing and who gets to frame your life, your community’s life —

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: — the life of Palestinians. Can you talk more about that? Who is the perfect victim, and who isn’t? You begin with, and you had little postcards at your opening event last night at the Judson Church, “even if! even if! even if!”

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Yeah. Ultimately, “even if! even if! even if!” is the thesis of the book. It’s to say, you know, the demand of us is to be perfect victims. And by that, it means you have to kind of adhere to a certain civility, to be — to have proximity to whiteness, to, quote-unquote, “innocence,” to nonalignment, to to being nonpartisan, to all these kind of mythical adjectives that are demanded of you in the war zone.

And so, people will say the Israeli military killed this 15-year-old boy, and then the Israelis will say, “Well, he was throwing a Molotov cocktail.” And I think we should say, “Even if he was throwing a Molotov cocktail, they shouldn’t have killed him in the first place, because the Israeli occupation has no right to be there in the first place. Even if this person who was killed held bad views, or whatever you want to define bad views as, he shouldn’t be killed in the first place,” right? You want to tackle things at the root. You want to start at the very genesis of the issue, which is Israeli colonialism. All of these other things are irrelevant — my character, my disposition, my affect. These are irrelevant. But we live in a world where the oppressed are put on trial for their perceived biases and their perceived bigotries. Meanwhile, the perpetrators can get away with it and can continue to enact systemic violence against us and get away with it.

AMY GOODMAN: You talk a lot about dehumanization and how it happens. Talk about that and how you feel is the most powerful way to be humanized, to humanize your own population, people.

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Well, there is, you know, the dehumanization that says you are hordes and you are insects and you are vermin. You know, that’s very explicit. But there’s also the very sinister implicit dehumanization. In the book, I say it’s the refusal to look us in the eye. But it’s kind of the refusal to acknowledge that we, like others, have the rights and the needs to defend ourselves, to resist, to anger, to hatred, to disdain, to all the sentiments. Right? When people say, “We are humanizing Palestinians,” they’re not really humanizing Palestinians. They’re saying, “We’re going to give this Palestinian a very restrictive script to fit in.” And the true way to be human is to cover the full spectrum of humanity, the full scope of humanity, that includes all of the human sentiments. And again, it is rooted in a very, very fallacious logic, the idea that the oppressed must live a life in cross-examination.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk, as you do in your book and your conversations, about the difference in the characterization of resistance? You compare how the Western media covers Ukraine resisting the occupation to those who resist the Israeli occupation, in the different approach.

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Yeah, I mean, the double standard is really flagrant. And I think we also should move past the double standard. But I think it’s worth mentioning. You know, I think the most absurd of these examples was I saw in the New York Post a headline that called a Ukrainian suicide bomber “heroic.” And I thought I was hallucinating, because, you know, I thought all my life suicide bombing was bad. And, you know, Sky News, I think it was, held what essentially could be described as a Molotov-making cocktail. And then you open the pages of The New York Times, they’re interviewing Ukrainian psychologists who describe hatred of all Russians as, you know, a formative energy — I’m paraphrasing here. And you open other pages of The New York Times, and they’re kind of glorifying or romanticizing Ukrainian police and Ukrainian military wearing civilian clothes, quote, “blending in” to the population — things that they would accuse Palestinians of hiding behind human shields for.

So, this kind of double standard says to you that there is not really a misunderstanding of resistance in the Western mind. There is just a rejection of resistance when it comes from the Indigenous population or from the population that threatens the status quo of the empire as it stands today.

AMY GOODMAN: You talk about Palestinians being defanged.

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Mm-hmm.

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean?

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Defanged as in, like, nonthreatening, nonoffensive. In order for you to be allowed the microphone or in order for you to be allowed into mainstream spaces, you have to make certain concessions. You are demanded to make certain concessions, to say that you’re not like — you’re nonviolent, and you don’t hate your oppressors, and you want peace, and you want coexistence. And you’re making all of these disclaimers before you even get to your talking point. And I know this from experience, as a child seeing diplomats coming into our living room. I would do this proclamation of, you know, “I don’t hate Jews, and I don’t want to throw anyone into the sea, and all these tropes that you’ve heard about me are true.” And then 15 minutes pass, and then I finally say, “And there are settlers in my house.” But that —

AMY GOODMAN: And explain, for people who didn’t see Part 1 of this conversation, Sheikh Jarrah and what you mean by there are settlers in your house.

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Well, I mean in the literal sense. In 1972, there were many settler organizations that claimed our houses as theirs by divine decree, and they started to try to kick us out of our homes using an asymmetrical Israeli judiciary. And obviously, the situation in Sheikh Jarrah is not unique. It’s happening all across Palestine, all across historic Palestine, in many, many communities. It was just so that our neighborhood was one of the few neighborhoods lucky enough to get media scrutiny.

AMY GOODMAN: You were arrested at that time?

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: I was arrested and detained multiple times, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: What made you decide to leave? And do you consider yourself having left or just visiting the U.S. and Britain?

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Well, I was already gone. I was already at CUNY when the Sheikh Jarrah stuff started to happen. I was already at CUNY doing my master’s. And I just decided to come back for the campaign to be with my family and friends. And, you know, I’ve lived — ever since I’ve come here, I’ve lived, you know, half of the year here, half of the year there. But since October 7th, and since the kind of — since the kind of uptick in crackdown, or, like, you know, the unprecedented level of crackdown on dissent, on activism, on anti-colonial sentiment, it’s been a bit hard. I’ve been advised, you know, not to return just for security, for safety reasons.

I mean, I give the dedication to my dear, dear, dear, dear friend Omar, who I really hope he’s doing OK. You know, he is one of the many, many Palestinians who have been held for many months on end, without charge or trial, on what the Israelis call administrative detention. And, you know, the Palestinian prisoners right now, the political prisoners right now, are suffering abhorrent conditions. We are not hearing much about it, but so many of them have skin conditions, like scabies. So many of them have been starved, tortured. We heard about sexual abuse in prison, rapes. We’ve seen horrific videos. And, you know, the Israelis have always been incredibly abusive towards Palestinian political prisoners, but in the past 15 months, it has gotten to unprecedented levels of brutality.

AMY GOODMAN: And can you talk, as a writer, about the writing of your book, Perfect Victims, where you were as you — I mean, you’ve written this over the last years as the Israeli assault on Gaza has unfolded, the tens of thousands of Palestinians who have been killed. President Trump himself calls it a demolition site which is unlivable. Of course, his solution is — he talks about it as a great real estate deal. It can be the “Riviera of the Middle East,” and Palestinians cannot be a part of that, he says. This is his latest in this last few days, saying they should not have a right of return.

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: I mean, to write a book in the shadow of genocide is a quite, I would say, difficult task, but I think it’s also like an arrogant task, particularly if you’re trying to write conclusions about this genocide. And I don’t think I tried to do that much in the book. I was trying to really tackle advocacy and media framing and how we talk to each other and how our allies and so-called allies talk to us and what they demand of us.

But it was — you know, you’re constantly, first of all, confronted with the enormity of the moment that we were living in, to see people being, quite literally, burnt alive or people hanging from ceiling fans, people being mutilated by the Israeli military. And you are confronted with the question of the insufficiency of words and of the written language and what is the — what even is the point, right?

And there comes a point where you have to reject this kind of nihilism or this kind of pessimism and decide for yourself that to be — you know, it’s the least that you can do is to try to raise the ceiling. I say “to raise the ceiling of what is permissible” in the beginning of the book, but really, like, to say — to see so many students being policed and to see so many people being bombed, and you see your platform, and you see that you’re a person who people who will listen to, and you think to yourself, “What is — what is it that I can do to really raise the ceiling, to make it easier for others to say what they need to say?”

And obviously, this book has been — you know, it has my name on the cover, but it’s a million people, so a million people who have worked on it, from my editors and my publishers, but also just my mentors and friends and people, you know, in Palestine, who have really, like, shaped my analysis throughout the years.

AMY GOODMAN: You talk about warning about overvictimization. I mean, in fact, you can’t say enough about the horror that has taken place, and yet how — talk about the dangers of overvictimization and what that means when it comes to people having agency.

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: Yeah, when we editorialize a victim past — like, somebody has suffered a certain atrocity, and we try to editorialize that even further, we are kind of implying that that atrocity they have suffered is not enough and that they have needed to suffer something further for them to be compelling.

And I’ll even implicate myself in this. I was writing about a Palestinian American man named Omar Assad, kind of critiquing the employment of citizenship in our advocacy tactics and saying how shortsighted it is. And this is a man, a Palestinian martyr, who has been bound, gagged by the Israeli military and left to die in the cold. And I remember when I was writing about him, I spent a substantial amount of time looking for an article that confirmed that he had also been beaten, because something within me told me it wasn’t enough that he had been blindfolded and left to die. I needed him somehow to be beaten, as well.

You ask yourself, “What is it that has drilled these tendencies into me?” And it’s dangerous, because it means that they can always move the goal posts. It means that their brutality can never be enough, that there is something that can always go further. But I say, even if the brutality they enact against us is merely bureaucratic, even if they were polite in the way that they kill us, that still is unacceptable. That is still deplorable. Even if, you know, they merely blindfolded him and saved him right before he was dead, that still is deplorable. You know, we do not need to overvictimize.

And also, there is the opposite end of that, which is the, you know, treating people as though they are heroes or as though they are just, you know, incapable of feeling pain or just able to withstand any circumstances. And that, too, is a form of dehumanization. We must understand that people are complex and have — you know, it’s quite a basic — it’s quite a basic thesis that I’m saying here. But, you know, you challenge the reader, you challenge the listener, to really challenge and interrogate their biases, and they will agree with you in theory, but oftentimes they will either want to strip somebody of their agency completely by saying they turned the other cheek all the time and they would never hurt a fly and they loved their oppressors even as they killed them, or by saying that they are, you know, infallible heroes that couldn’t care less about the brutality being waged against them.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to end this conversation where you begin the book, and I was wondering if you can read from “the sniper’s hands are clean of blood,” and start with the quote and where the quote is from.

MOHAMMED EL-KURD: This is Padraic Fiacc’s — I hope I said the name right. He’s an Irish poet who my friend Rashin introduced me to. And his quote goes — it’s from a poem. And the quote goes:

“And the men are men and the women are men

And the children are men!”

And I’ll read from the book.

“WE DIE A LOT. We die in fleeting headlines, in between breaths. Our death is so quotidian that journalists report it as though they’re reporting the weather: Cloudy skies, light showers, and 3,000 Palestinians dead in the past ten days. And much like the weather, only God is responsible — not armed settlers, not targeted drone strikes.

“We pay no heed to the corpses in our fields. Their existence is monotonous, predictable. The slaughter is so relentless, it is almost expected — anticipated — by the soon-to-be-slain. Their wrists, big and tiny, bound with zip ties in the back of police cars. Death is everywhere. Even metaphor is a casualty of war. The figurative has become painfully literal: bloodied beards, furniture in trees, a limb hanging from a ceiling fan, women giving birth on the concrete. Etcetera. Are we too acquainted with the horrific? What was once horrifying, what once a harbinger of doom, now blends into the terrain; death is now a boring scarecrow. Even when the ravens grow louder, their croaking falls on disinterested ears. No sanctity is left in this death. No deities come to the rescue. We die forsaken. We die a lot in abandonment.

“Our massacres are only interrupted by commercial breaks. Judges legalize them. Correspondents kill us with passive voice. If we are lucky, diplomats say that our death concerns them, but they never mention the culprit, let alone condemn the culprit. Politicians, inert, inept, or complicit, fund our demise, then feign sympathy, if any. Academics stand idle. That is, until the dust settles, then they will write books about what should have been. Coin terms and such. Lecture us in the past tense. And the vultures, even in our midst, will tour museums glorifying, romanticizing what they once condemned, what they did not deign to defend — our resistance — mystifying it, depoliticizing it, commercializing it. The vultures will make sculptures out of our flesh.

“And we die.”

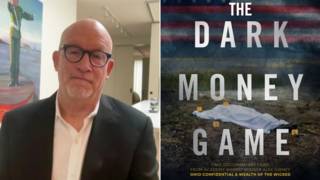

AMY GOODMAN: Mohammed El-Kurd, Palestinian journalist, poet, author. His new book is out today. It’s called Perfect Victims: And the Politics of Appeal, To see our Part 1 of the interview, go to democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options