Topics

Guests

- Paul Barrettassistant managing editor at Bloomberg Businessweek whose cover story is called “It’s Global Warming, Stupid.”

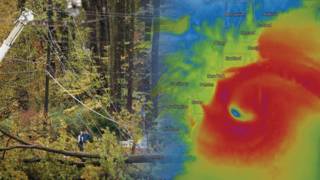

The link between climate change and the devastation wrought by Superstorm Sandy across much of the Northeast was brought into focus Thursday when New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg endorsed President Obama, citing his policies on the environment. Just days before the elections, Bloomberg wrote: “We need leadership from the White House — and over the past four years, President Barack Obama has taken major steps to reduce our carbon consumption.” Bloomberg’s endorsement is particularly striking because much of the news media has barely mentioned climate change even in the lead-up or aftermath of the superstorm. There were also no questions addressed to the presidential candidates on climate change in the course of the presidential debates. One of the news outlets that has broken the silence on climate is the magazine Bloomberg Businessweek, whose cover story this week is called “It’s Global Warming, Stupid.” We’re joined by the story’s author and the magazine’s assistant managing editor, Paul Barrett. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. We’re broadcasting from Missouri Public Television in St. Louis and in New York City, where the link between climate change and the devastation wrought by Superstorm Sandy across much of the Northeast has been brought into focus when New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg endorsed President Obama, citing his support for the environment.

Just days before the elections, Bloomberg announced his decision in an op-ed entitled, “A Vote for a President to Lead on Climate Change.=,” writing, quote, “We need leadership from the White House — and over the past four years, President Barack Obama has taken major steps to reduce our carbon consumption.” Bloomberg compared the records of Obama and Mitt Romney. He wrote, quote, “One sees climate change as an urgent problem that threatens our planet; one does not. I want our president to place scientific evidence and risk management above electoral politics.”

Bloomberg’s endorsement is particularly striking because much of the news media has barely mentioned climate change, even in the lead-up or aftermath of the superstorm. There were also no questions addressed to the presidential candidates on climate change in the course of the three presidential debates. Also, Mayor Bloomberg was a Republican who turned independent.

One of the news outlets that’s broken the silence on climate change is the magazine Bloomberg Businessweek. The cover story this week is called “It’s Global Warming, Stupid.” To talk more about the issue, we’re joined by the author of the cover story, Paul Barrett, assistant managing editor at Bloomberg Businessweek.

Paul, it’s great to see you. Lay out this article, “It’s Global Warming, Stupid.”

PAUL BARRETT: Yeah, good morning, Amy.

What we tried to do with the article is make a very sort of straightforward survey of what information we know about climate change and how it relates to this most recent very extreme storm. And I think the crucial point here, at least to start with, is that you’re not—we’re not in a position to say that global warming caused this particular storm, but what we are in a position to say, and what the overwhelming majority of scientists, people who know about climate, who know about weather, are saying, is that as a result of climate change—and this is a man-made climate change—we have a larger environment, a larger atmospheric situation in which storms are going to be more severe and in which we are likely to see very, very difficult storms such as this one with more frequency.

In our article, I quoted a guy from the Environmental Defense Fund named Eric Pooley, who knows a lot about this, and Eric made the analogy to baseball. He said—in connection with the disgraced slugger Barry Bonds, he said, you couldn’t attribute Bonds’s use of steroids to any one home run he hit, but only a fool would think that steroids had nothing to do with the number of home runs that Barry Bonds ultimately hit and how far he hit them. And I think that that’s a good analogy for people who may be a little science-phobic, like I am, to think about this. It’s not that you can point to one storm and say, “Ah, global warming caused that,” because there are many factors that go into extreme weather. But overall, the fact that the oceans are higher, that the water is warmer, that there’s more moisture in the atmosphere, that the Arctic ice is melting, those are facts, and it’s time to accept those facts.

AMY GOODMAN: In fact, when you talk about the Arctic ice melting, you talk about what scientists say may be a direct link between that and what you’re experiencing in New York and people are experiencing along the East Coast now.

PAUL BARRETT: That’s right. That and what you’re talking about now is something specific to Sandy. One of the interesting and very relevant things about this particular storm is that it took that very hard, sharp left turn into the East Coast of the United States rather than drifting out to sea. And one of the theories about why it did that has to do with atmospheric patterns that begin over the Arctic Ocean and that resulted in cold air coming down over Canada and colliding with the warm air from the hurricane, forming not just an ordinary storm, but this superstorm, as you’ve been calling it. And there’s been work on climate, on—research done that suggests that the melting of the Arctic ice contributed to these atmospheric patterns that pushed the cold air down, and that, in a sense, super-energized the storm, added a lot of energy and geographic reach to the storm, and made it not just an ordinary hurricane, but this much more extreme event. And that’s a good illustration. It’s not that there would not have been a hurricane. There would have been a hurricane either way, but this became an extraordinary hurricane combined with this cold air from over Canada, it seems, as a result of the larger atmospheric patterns changing.

AMY GOODMAN: Paul, you talk about the—the European insurance company, Re. Can you talk about what they’re seeing and saying?

PAUL BARRETT: Yeah, absolutely. I thought it was relevant, after surveying some of the science, to talk about this really interesting report from a German reinsurance company called Munich Re. The “Re” refers to reinsurance, which is the insurance that is purchased by other insurance companies as back-up insurance. Munich Re is a company that, in one sense, compiles data in a very kind of bloodless, profit-oriented way in order to figure out what the costs are going to be related to storm hazards, among other disasters.

And Munich Re put this report out on October 17th, before the storm, before we had any sense that it was going to be as extreme as it was. And what it reported was that basically extreme weather has been—has gotten more frequent, more intense, particularly as it happens in North America, and the insurance company is saying that they are now beyond the debate over whether climate change is real. They have accepted that, and they are calling on industry to deal with it as a statistical reality. And I thought that was a nice accompaniment to the scientific research, because the Munich Re guys are not doing basic climate research; they’re simply surveying the money that they pay out over time. And they’re saying, “We’ve been paying out more billions in recent decades than we had anticipated. We see a trend, and we can see no explanation other than the relationship to global warming.”

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, in fact, even the Pentagon, right, for years, even under the Bush administration, has been saying this is one of the greatest threats in terms of national security in the 21st century, everything from, well, just what we’re seeing now, the catastrophic effects, to climate refugees and how you deal with people who are moving from one place to another because they’re so threatened in—at their—in their home country.

PAUL BARRETT: Yeah, that’s right. And I think one of the interesting questions is when we in the United States will accept that reality. And you can see that in sort of mundane, ordinary, day-to-day human terms. Will we accept that actually it no longer works to live on barrier islands that are at sea level right on the ocean, when there are going to be hurricanes every year? Because while hurricanes have been part of that way of life for a long time, if the hurricanes are now going to be more frequent, more intense, and are going to continue to wash the towns away, we have to ask ourselves serious questions as to whether we want to spend the billions of dollars to keep rebuilding those communities. At the same time, we’re not going to pick—pack up Manhattan and move it away. So there’s going to—we’re going to have to seriously address whether we need storm protections around lower Manhattan similar to those that we have in coastal communities like New Orleans. I mean, this is a very serious question. I think we’re going, over time, to have to admit that we—if we’re going to live and work in lower Manhattan, we’re going to need levees and storm protection systems there such as we’ve had in other parts of the country.

AMY GOODMAN: And what about that issue? I mean, you are editor at Bloomberg Businessweek. The whole issue of these coastal communities—I mean, it’s heartbreaking to see the catastrophe in New Jersey, for example. But people who are building in these coastal communities, I mean, the breaks that are given for second homes, and then the insurance that must be paid for these very vulnerable areas that are then built on.

PAUL BARRETT: Right. Well, this is not just a question of the private marketplace at work, because in fact in a lot of these communities, it’s no longer possible to get private insurance. The insurance companies have basically had it with that marketplace, realizing as they do, in their strictly dollars-and-cents analysis, that you can’t profitably insure towns on barrier islands along the Atlantic. So, in fact, you and I are insuring those towns through federally sponsored flood insurance. And we need to make a policy decision, collectively as a country, do we want to continue to extend that insurance? Because we’re basically encouraging people to rebuild their houses and their restaurants and so forth in those communities, and I think we need to have a serious debate about whether that makes any sense anymore.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Paul Barrett, assistant managing editor at Bloomberg Businessweek. His cover story is “It’s Global Warming, Stupid.” Paul, the newspaper—the magazine is Bloomberg Businessweek, right? Bloomberg bought Businessweek.

PAUL BARRETT: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: And at the same time your piece has come out—

PAUL BARRETT: Right.

AMY GOODMAN: —New York City Mayor Bloomberg, who was a Republican, now an independent, who both parties have been courting madly to get his support, came out at the same time as your piece coming out, saying he’s endorsing President Obama. Talk about the significance of this.

PAUL BARRETT: Well, the first thing to say is that it’s totally legitimate and obvious to observe that coincidence. The second thing to say is that I—my bosses at the magazine did not get a phone call from the mayor or any sort of instruction to do this piece. He doesn’t participate in any way in the day-to-day, week-to-week, month-to-month or year-to-year activities of the magazine. We simply have nothing directly to do to him, although he does own the magazine. That’s—you know, don’t want to gainsay that. So I was as surprised as anybody else when, shortly after our piece went up online, the mayor came out with his endorsement. But at the same time, I think that—

AMY GOODMAN: Paul, maybe it’s—maybe it’s not—

PAUL BARRETT: You know, I think it’s a significant event—

AMY GOODMAN: Paul, maybe it’s not you—maybe it’s not Mayor Bloomberg influencing you; maybe your piece influenced Mayor Bloomberg.

PAUL BARRETT: Oh, gosh, I would never presume that. I think Mayor Bloomberg can make up his own mind on these things. And his endorsement, of course, emphasized more than just climate change. He talked about issues ranging from reproductive freedom to gun control and so forth. So I have to say, I think the mayor makes up his own mind and doesn’t need to look to me or to the magazine for guidance.

But I think it is significant, even if there wasn’t any kind of cause-and-effect relationship, significant just to see the issue being reintroduced into the political debate, because as your setup piece noted, it’s pretty remarkable that we’ve gone through an intense presidential campaign with this large global issue absent from the discussion. And one would think, and one would hope, and clearly the mayor desires to see the issue being taken seriously. We have two candidates. Neither of them talked about the issue very much, or at all, in the campaign. But one of the candidates has actually belittled the issue. I mean, Mitt Romney, in his acceptance speech at the—at the Republican National Convention, actually purported to make fun of President Obama for ever having expressed any interest in the rising oceans and the state of the health of the planet. And I think it is significant that you’ve got one presidential candidate who—you know, who just refers to the issue sarcastically, as if it’s—as if it’s not really an issue, whereas President Obama, whether you like him or don’t like him, has taken some modest steps during his presidency to address this issue. He did, after all, back the cap-and-trade legislation that passed the House of Representatives in 2009, although it then died in the Senate in 2010 as a result of Republican opposition.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, I wish I could be playing for you some of the comments of Mitt Romney and also President Obama in the debates. As you said, never once in the three debates was climate change mentioned, or global warming, neither by the candidates nor by our colleagues in the press, did not—

PAUL BARRETT: That’s true.

AMY GOODMAN: —find it important enough to ask a question about global warming. I can’t play the clips, because, well, our studio remains down, blacked out, without electricity in New York City. But they are famous enough that just talking about them, people remember. Quote Mitt Romney in his acceptance speech at the Republican convention, and then quote President Obama in the debates—it seemed they couldn’t out-drill each other enough, in talking about their support for oil drilling, Paul.

PAUL BARRETT: Well, not just oil drilling, but also for the use of coal, which is, you know, by far, when you’re talking about the electricity market, the fossil fuel that contributes the most carbon dioxide when it’s burned, and there—there was always a competition over who loved coal more.

The strange thing about that is that if you know what Obama’s actual record is, there was a certain dissonance between his record and his comments on coal. He’s actually—as a result of regulations that his administration put in place, rules they’ve proposed, they have done quite a bit in terms of putting ceilings on emissions of carbon dioxide, mercury, sulfur dioxide, that have actually already resulted in big energy companies, utilities, closing a lot of old, dirty coal plants. So we have made some small steps in the direction of shifting from coal to fuels like natural gas, which emits something like half the carbon dioxide that coal does.

But in the presidential campaign, clearly, President Obama and his advisers made a strategic decision that they were not going to run on that record; instead, I guess because they see the economy is very fragile and because they didn’t want to take this on head-on, they ended up dueling with Romney over who was more enthusiastic about drilling oil and mining coal.

AMY GOODMAN: And the comment of Governor Romney, Massachusetts Governor Romney, though he doesn’t like to seem to remind us of this, when he famously said in the—at the Republican convention in his nomination—his acceptance speech, “My promise is to help you and your family,” after saying, “President Obama promised to begin to slow the rise of the oceans and heal the planet. My promise is to help you and your family.” Interesting how those two issues have merged now, Paul.

PAUL BARRETT: Well, they have—they have merged, because, you know, as we pointed out in our piece, there are an awful lot of families in New Jersey, on Staten Island, elsewhere in the mid-Atlantic, who right now need an awful lot of help—and a lot of expensive help, by the way—as a result of the rising oceans. I mean, you know, when you have higher sea levels, it means that a storm that whips up the sea is going to do more damage. So that opposition that Romney tried to set up really is a false one, the idea that making progress on the environment is somehow at odds with helping ordinary families. That’s just simply not true. You know, we’re going to end up with losses somewhere near $40 billion, $50 billion. That’s going to come out of taxpayers’ pockets, in part. And that is a very sort of hard-nosed, unemotional illustration that the interests of American families are not at odds with environmental concerns. These things are intertwined.

AMY GOODMAN: And yet, as you point out in your piece, Paul Barrett, it’s not as if Mitt Romney always felt this way. You write, “Mitt Romney too has a history of tackling climate change.” But that’s when he was governor of Massachusetts, which he doesn’t like to remind us of.

PAUL BARRETT: Right. No, no, there’s a very close parallel here, for example, between Romney’s positions on the environment and Romney’s positions on financing healthcare. I mean, Romney was, as governor, a pioneer of moving Massachusetts toward a healthcare system where insurance was available for all people, not just as a humane gesture—although it is a humane gesture—but also because in the long run that makes financial sense. And he has, as we all know, run away from his position on “Romneycare” and somehow suggested that that was different from what the president tried to do on a—what the president accomplished on a national level. And similarly, now he has tried to forget about his relatively progressive stance on the environment when he was governor of Massachusetts. And you see this all across the board. I mean, there was a time when he tried to appeal to Planned Parenthood as a strong supporter of what Planned Parenthood does, and today he wants to defund Planned Parenthood. When he was governor, he was an advocate of certain forms of gun control, and today he can’t be friendly enough with the NRA in opposing, even discussing, the issue of gun control. So, you see this pattern all across the board. He’s moved from the center-left all the way over to the far right on a lot of these issues.

AMY GOODMAN: Paul, speaking of defunding, the issue that Governor Romney has raised in talking about defunding FEMA, getting rid of FEMA.

PAUL BARRETT: Yeah. Well, that’s particularly a fascinating one. You’re referring, of course, to his comment during one of the Republican primary debates when he was asked directly, “What would you do about FEMA? Would you—as part of your efforts to shrink the federal government, would you send FEMA’s responsibilities back to the states?” And his immediate answer was, “Absolutely.” He said, “Not only would that be a good idea, but possibly you would even turn it over to the private sector,” raising the prospect of, you know, what I called in the piece a sort of pay-as-you-go rooftop rescue program, where if you had the money, you could be rescued from your flooded house, but if you didn’t have the money, well, you know, too bad, which I think is something that would really be abhorrent to most Americans. I mean, you know, the time when you really want and appreciate, you know, big government, as it’s sometimes derided, we need to see the National Guard, you need to see help coming from the federal government, is when there’s an all-out disaster. And the idea that you would reflexively say, “Shut down FEMA, let the free market handle this problem,” is, to me—well, it’s troubling, I would say, at a minimum.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, your piece, “Let the states fend for themselves or, better yet, put the private sector in charge.” You write, “Pay-as-you-go rooftop rescue service may appeal to plutocrats; when the flood waters are rising, ordinary folks welcome the National Guard.” What privatization means, this picture you create, you know, that you evoke, of these rooftops, where if you’ve paid for some private security, maybe you’ll get whisked away on your rooftop.

PAUL BARRETT: Yeah, it’s hard to conceive of, and I think it’s—it’s an—I don’t even know whether Romney himself, when he suggested that the private sector was the appropriate institution to deal with this—I don’t know if he was making a serious policy proposal or whether he was just pandering to the anti-government, anti-regulatory ideology that has come to grip so much of the Republican Party. But either way, it’s a—you know, it’s an unsettling notion that you would just, with the wave of a hand, shrug off the role of government in the midst of a crisis-type situation.

AMY GOODMAN: Paul, before you go, I wanted to ask you about this issue of gun control that Mayor Bloomberg also raised in citing his endorsement for—for President Obama. Oh, and before I even ask you that, one quick question: the significance of having one of Mitt Romney’s biggest boosters, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, being, you know, there with President Obama, saying, sort of, “To hell with politics. This is about people’s lives and being there on the coast.” Do you think we could see a similar trans—you know, endorsement, where Chris Christie says President Obama is best on this issue?

PAUL BARRETT: I doubt he’d actually say that in so many words. But I think he actually did say something with—you know, with body language and with political theater. You know, I think it’s a very, very important distinction. You saw Chris Christie snap into pragmatic governor mode, a mode much more similar to the way, you know, for example, Mike Bloomberg conducts himself as mayor of the city. Sure, he’s got ideological views, but when there’s a real crunch and a real need for leadership, he’s not going to stand on—you know, he’s not going to lean toward political posturing, and he’s certainly not going to, at that point, pretend that the federal government has nothing to do with the health and welfare of American society.

And I think Christie was communicating something significant in how he worked with the president and singled the president out for praise and, by the way, singled FEMA out for praise, saying that under the Obama administration FEMA actually is functioning effectively. I mean, that’s a big difference. If you’re—if you have an administration that is constantly dumping on the federal government’s capabilities and undermining the ability of agencies to do what they’re supposed to do, well, then you’re guaranteeing that they’ll be ineffective when you need them. And we saw that in connection with Katrina in New Orleans and how poorly FEMA performed then. I think it’s a pretty striking contrast that now you have a very vociferous Republican governor of New Jersey who’s saying, “Hey, FEMA was there right away and right on—you know, was really on its game.” So, it is possible for the government to perform poorly, and it’s possible for the government to perform well. And I think the little political drama we saw play out in New Jersey was well worth considering.

Media Options