Related

Guests

- Kumi Naidooexecutive director of Greenpeace.

Leaders from more than 100 countries are meeting today in Brazil for the start of the Rio+20 Earth Summit, the largest United Nations conference ever. The conference comes 20 years after the U.N. Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro pledged to protect the planet by endorsing treaties on biodiversity and climate change. Little has been done in the intervening years to reach development goals in areas like food security, water, global warming and energy. Although negotiators have already agreed on a draft document to be approved by world leaders, many groups working on environmental and poverty issues have criticized the draft agreement, saying it is far too weak. We go to Rio to speak with Kumi Naidoo, executive director of Greenpeace. [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Leaders from over a hundred countries are meeting today in Brazil for the start of the Rio+20 Earth Summit, the largest United Nations conference ever. The conference comes 20 years after the U.N. Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro pledged to protect the planet by endorsing treaties on biodiversity and climate change. Little has been done in the intervening years to reach development goals in areas like food security, water, global warming and energy. U.N. Environment Program executive director Achim Steiner said leaders had to show more commitment now than they did 20 years ago.

ACHIM STEINER: Because 20 years after Rio 1992, on virtually all the megatrends that we described, we cannot stand before our either elders or children and claim that the last 20 years have succeeded in turning these trends around.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: All the negotiators have already agreed on a draft document to be approved by world leaders. Many groups working on environmental and poverty issues have criticized the draft agreement, saying it is far too weak. This is Greenpeace political director Daniel Mittler.

DANIEL MITTLER: Any progress that you hear about in press conferences is about progress to water down the text to avoid commitment and to—in reality, governments are clearly here to do nothing and to commit to doing nothing.

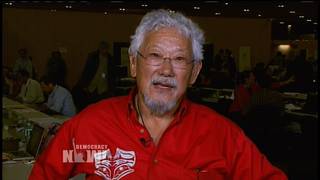

AMY GOODMAN: To discuss the Rio+20 summit and what’s likely to come out of it, we go to Rio now to talk to Kumi Naidoo, executive director of Greenpeace, who’s flown in from South Africa, where the last U.N. conference on climate change took place in December in Durban.

Kumi, welcome to Democracy Now! Can you talk about what you expect to come out of this summit, if anything?

KUMI NAIDOO: Thank you very much for having us.

Firstly, I think it’s important to note that 20 years after the original Earth Summit, as Achim Steiner from the United Nations Environment Program notes, on virtually all the commitments that were made, there are setbacks. Just to give you two, that carbon emissions has increased by 40 percent 20 years ago, since 20 years, and we’ve had 10 percent further biodiversity loss. So we come to this summit with a theme that the United Nations came up with, which was “The World We Want.” And I think that the mood here now, given that actually the text is seen as complete, even though the heads of state only start their meeting today, the Brazilian government has run a process which has meant that there is not very much room to change things in the text.

And while the—and somebody not familiar with United Nations speak could read through the declaration and think, “Oh, well, there are many things that sound good,” like there will language on oceans, for example, and ocean detection. But, in fact, basically, the more ambitious plan, for ocean rescue plan, because now it’s clear that if we do not have urgent intervention in our oceans, within four decades our oceans will be close to death. So, given the language that gets used — “seek to,” “endeavor to” and so on, which are all wiggle—room to wiggle out of commitments.

So, the people were hoping that we would have, if you want, [inaudible], that we would have a sustainable plan for the economy, basic equity, and basic ecological and environmental, you know, protection. And the mood here is actually quite down at the moment, because what we expected is that every state would come and make nice speeches, and there might be some bilateral, you know, meeting, there might be some announcement of this project here, that project there, but the text on the table is a betrayal of what the summit was supposed to be about.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: I want to turn to New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who spoke Tuesday in Rio.

MAYOR MICHAEL BLOOMBERG: Even as progress at the national and international levels has faltered, it’s fair to say the world’s cities have forged ahead. And the reason for that is clear. Mayors, the great pragmatists on the world stage, who are directly responsible for the well-being of the majority of the world’s people, just don’t have the luxury of simply talking about change but not delivering it.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Kumi Naidoo, your response to what New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg had to say?

KUMI NAIDOO: I’m in full agreement with what Mayor Bloomberg is saying. And, in fact, in the United States, as well as in, say, South Korea and several other countries—like, in South Korea, we had an event here with the mayor of Seoul in the middle of the summer, where he presented a completely different vision of what they are doing, how they are trying to get off nuclear, how they are trying to generate new green economy jobs. And it’s very, very inspiring. I mean, if we look at the United States’ example, while it’s been a dismal failure at the national federal level, there are so many signs of optimism at the local government level, as well as certain states doing the right thing. But the reality is, we need—the scale of the problem means that we have to have national leadership, you know, at the highest level in every country. I think what mayors are doing can also, of course, be improved, can be intensified, and so on, but without the national leadership on this issue, the scale of the problem is insufficient, you know, is so big that just mayors doing the right thing within “the best they can do” sort of approach is just not going to be good enough to avert catastrophic climate change and the range of other challenges that we face environmentally, as well as in terms of development, in terms of creating a more balanced and equitable world.

AMY GOODMAN: Kumi Naidoo, can you talk about the significance of Rio+20, the largest U.N. summit ever—most importantly, what you think the world faces now around climate change? With your enormous disappointment with the draft that is being passed around, that was decided long before the meeting, this gathering, where tens of thousands of people are, what is at stake? And the fact that this is the largest U.N. summit, yet you don’t see something coming out of this, what has to be done?

KUMI NAIDOO: Well, let’s understand why the problem is so serious, right? Firstly, on climate change, the science has been telling us for at least a decade now that emissions must be, by 2015, in fact coming down. Right now, the situation is that nobody thinks—you know, sane-thinking person thinks that we will get there. In fact, if anything, emissions are actually going up. And there is a sense of cognitive dissonance, you know, where all the facts are there, but our political leaders, you know, just kind of are not willing to actually act on it. I mean, as long as—

AMY GOODMAN: Ten seconds. Kumi, we have 10 seconds.

KUMI NAIDOO: And secondly, I think oceans, forests, job creation, moving to a green economy, all of these issues are things that we expected progress, and sadly, it’s not there. And I think this is another reminder to citizens that we have take more leadership outside of formal processes and put pressure on our government.

AMY GOODMAN: Kumi, I want to thank you very much for being with us. Kumi Naidoo, executive director of Greenpeace, in Rio.

Media Options