Related

Guests

- Claudia Salernothe lead climate negotiator for Venezuela at the U.N. climate summit (COP 19) in Warsaw, Poland. She is the Venezuelan special envoy for climate change and also vice minister of foreign affairs for North America.

A group of 133 developing nations have walked out of a key part of the climate talks in Warsaw, Poland, amidst a conflict over how countries who have historically emitted the most greenhouse gases should be held financially responsible for some of the damage caused by extreme weather in nations with low carbon emissions. The United States, Australia, Canada and other industrialized countries are pushing for the issue — known as loss and damage — to be put off until after the 2015 climate talks in Paris. “When you see developed countries being so bold to tell you that they are not even considering reducing their emissions, that they are not even considering paying for the costs that those inactions have on the life of others, that is really rude and hard to handle it politically,” says Claudia Salerno, the lead climate negotiator for Venezuela, which is a member of the G77+China group that walked out. “We are heading to a point in which countries are not ready to take responsibility for their acts, and in this case, even more pathetic, they are not wanting to be.” Salerno became famous at the 2009 U.N. climate summit in Copenhagen when she banged her hand against the table in an attempt to be heard, hitting it so vigorously that it began to bleed. Her country is set to host a ministerial meeting next year ahead of the 2014 U.N. climate summit in Peru, where it will welcome the input of civil society.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We are broadcasting from Warsaw, Poland, at the U.N. climate summit, known as COP 19. A group of 133 developing nations and China walked out of a key part of the climate talks here in Warsaw early this morning over a dispute with industrialized nations. The conflict centers on how countries who have historically emitted the most greenhouse gases should be held financially responsible for damages caused by extreme weather. The United States, Australia, Canada and other industrialized countries are pushing for the issue, known as loss and damage, to be put off until after the 2015 climate talks in Paris.

The walkout occurred just hours after U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon discussed his plan to hold a special climate summit of world leaders in New York next September. He urged governments to put forth more ambitious plans to cut carbon emissions, saying, quote, “current pledges are simply inadequate.”

SECRETARY-GENERAL BAN KI-MOON: The latest IPCC report confirms that our planet is continuing to warm. Sea levels are rising, and ice caps are melting. Greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise. We are the first humans ever to breathe air with 400 ppm of carbon dioxide. Warmer ocean surface temperatures and higher sea levels contributed to the strength of Typhoon Haiyan and the devastation it caused the Philippines. This disaster is more than a wake-up call. It is a very serious alarm. Typhoon Haiyan puts an anguished human face on our struggle to combat the extreme weather and other consequences of climate change.

AMY GOODMAN: In other news from Warsaw, Poland’s prime minister, Donald Tusk, made a surprise move today when he dismissed his own environment minister, Marcin Korolec, who is serving as president of this summit, the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change. The minister, however, will continue to represent Poland in the ongoing climate talks here. His firing was part of a broader reshuffling of the Polish government, which included the firing of the minister of finance and a number of other ministers.

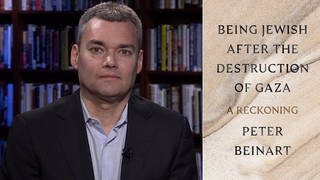

Well, we are joined here in Warsaw at the National Stadium, where the U.N. climate change summit is taking place, by Claudia Salerno, the lead climate negotiator for Venezuela here at COP 19. She is also Venezuela’s vice minister of foreign affairs for North America. Claudia Salerno became famous in 2009 at the Copenhagen climate summit, COP 15, when she banged her hand on the table in an attempt to be heard, hitting it so vigorously it began to bleed. This is what she said.

CLAUDIA SALERNO: [translated] Mr. President, do you think a sovereign country should have to make its hand bleed in order to raise the right to speak, because you simply do not want to hear what is happening? This hand, which is bleeding, wants to speak, and it has as much right as any of these which you call representative group of leaders.

AMY GOODMAN: That was in 2009. In 2011, at COP 17 in Durban, South Africa, Claudia Salerno stood up on a chair during a meeting in another attempt to be heard. Here’s Claudia Salerno speaking after she was recognized there.

CLAUDIA SALERNO: Mr. Chair, let me make this clear to the world: I requested the floor way before you gavel, and you ignore me. The whole world just witnessed how much you ignore me.

AMY GOODMAN: Claudia Salerno, the lead climate negotiator for Venezuela, joins us now here in Warsaw.

Welcome to Democracy Now!

CLAUDIA SALERNO: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: It’s great to have you with us. So, there you were three years ago banging your hand 'til it bled. Then, in Durban, South Africa, you're standing on a chair to be recognized. Today, I guess as Marcin Korolec was being fired as the environment minister here in Poland, you were the president for the moment—

CLAUDIA SALERNO: Yeah, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —of this COP.

CLAUDIA SALERNO: Yeah, usually, as I am a Korolec representative at the bureau, bureau members have to take upon the chair when he needs to leave for a certain reason. I had no clue that I was chairing for that specific reason, that, yes, I was supposed to be, at a certain point in the COP, taking the presidency for him.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, it’s very interesting, because yesterday was Gender Day here at the COP, the Conference of Parties, the U.N. climate summit. What about women’s representation here at these climate talks?

CLAUDIA SALERNO: In general, women are also—always very strong in their positions. I think Latin America is one of the regions that has the largest women representation at head of their delegations, and also we see some women coming from the African countries. In general, gender is a quite disregarded issue in the formal agenda of the convention, although when women have a very important role in the mitigation process, as such, and in the fighting for climate change and also in adaptation.

AMY GOODMAN: When you mean “mitigation,” what do you mean? And when you mean “adaptation”?

CLAUDIA SALERNO: All actions that can be done to try to reduce emissions. And as we consider that women are driven, for example, education at the home stages, because, you know, those are the more important first steps to create a new citizenship and a new kind of human and a new different relationship with those humans with the environment, and those are actually women, the ones that are responsible to take those first responsibilities towards the future generations, the one that we are raising.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about what happened early this morning? Venezuela is part of the Group of 77 and China. They walked out of the climate talks about 4:00 this morning.

CLAUDIA SALERNO: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Why?

CLAUDIA SALERNO: Loss and damage, as it’s known, is an agenda that we never wanted to have in the first place. I called this the agenda of resignation, when things are going so wrong that you have to claim only to rich countries to pay for the damages and the losses that they are causing you with their attitudes. That is the most dramatic and pathetic agenda that we have on the table. And although when the situation that—for example, the typhoon recently in Philippines is showing that the situation is dramatical to the point of humanitary needs. When you see developed countries being so bold to tell you that they are not even considering reducing their emissions, but they are not even considering paying for the costs that those inactions have in the life of others, that is really rude and hard to handle it politically, that we are heading to a point in which countries are not ready to take responsibility for their acts. And in this case, even more pathetic, they are not wanting to be hold responsible for their inaction and their lack of responsibility with humanity and the future generations.

AMY GOODMAN: Explain who the 133 countries are, because G-77 means Group of 77, but 133 countries walked out.

CLAUDIA SALERNO: It’s composed by all developing countries nations in the settings that—the definitions of economical development that the U.N. has made. It’s a group, a very old group, started exactly with 69, that they became growing and growing, and now it is 133 countries plus China.

AMY GOODMAN: You say this is an economic conference, really, not a climate conference. Why?

CLAUDIA SALERNO: Because every single action that you need to make to reduce emissions gets actually to—in the land, it gets to the production of something. Economies produce emissions. And when you are talking politically to reduce their emissions, those reductions are going to touch certain economies, certain kind of productions, certain lines of commercial trading relationships. So that is the kind of agreement that we need to make. But there has been a misunderstanding link with that, that actually an economical discussion on how to produce better, how to make things in a better way, to more sustainable way, became actually a market opportunity discussion on how to take advantage of the pollution that we are causing. And that is actually the wrong interpretation that developed countries have of this process.

AMY GOODMAN: Ninety-five percent of your economy, of Venezuela, is based on oil exports. How do you diminish that?

CLAUDIA SALERNO: Actually, Venezuela is known, very known, as an oil producer, but is also a very green country. We were one of the first ones in the region creating a Ministry of Environment and the first one creating a penal law for environment. And we have a large development in the environmental side, signifying for us—for example, the 60 percent of our territory are protected areas in some kind of form of legality, in untouched areas, and almost 50 percent of the territory has been untouched. That actually make us having a GDP depending highly on the oil economy, but producing emissions that represent currently 0.48 percent of the total global emissions. And that is quite difficult to set for an oil producer, but we have reached that.

AMY GOODMAN: Right next to us is the advertisement for next year’s COP, COP 20, that will take place in Lima, Peru. If anyone hears noise during the show, it’s because they’re blending drinks downstairs to give it out to prepare people for the Lima trip. But Venezuela, you’re going to hold a pre-COP, what is known as that. Now, Democracy Now!, we’ve been at the last four summits, but also the fifth was the Bolivia People’s Summit.

CLAUDIA SALERNO: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: This pre-COP that you’re holding in Venezuela, what will it be about? It’s not formally recognized as a U.N. meeting.

CLAUDIA SALERNO: No, it’s not, but it’s part of the process, the formal convention process. It’s actually an informal meeting, gathering of ministers, about 40 or 50 strong leaders in the process, to try to have a sense, in advance of the COP, of how is the political readiness to agree on certain things. What Venezuela decided, when we were elected to host this pre-COP meeting, this ministerial consultation, is that we have been seeing this tendency to make this a business and market profit convention, sadly taking advantage of the pollution that some are causing. And if we are intended to sign an agreement in 2015, Venezuela said that we just not are going to be able to do it as governments alone; we need to get involved with our people and civil society in this process, together as one, and then to create this alliance.

So, Venezuela next year will host the first formal social consultation of every single social movement involved in the climate change agenda, with three preparation processes in advance of that pre-COP. And then, for the first time, instead of having ministers listening to each other’s the same statements and stubbornness, we are going to have ministers listen to their people about what is the kind of ambition and the kind of agreement the world wants to have—but the world’s side, not the governmental approach.

AMY GOODMAN: Democracy Now! got a hold of these confidential documents that came out of Secretary of State John Kerry’s office, directing the U.N. climate change negotiators not to talk about loss and damage, which they fear will become a major issue here at the COP, which it certainly has, but to call it “blame and liability.” What do you think about that?

CLAUDIA SALERNO: It is a lot of that since Copenhagen. Once that those countries fail to a certain approach, now the whole political game is like to blame others for not doing what they are supposed to do, instead of each other’s taking their own responsibility for their own acts and act without asking others. And then this other tendency of developed countries that say they are leading, but leading from behind, pushing others to do what they are not ready to do to their own economies. So they are actually expecting developing countries to stop their development to then to be able to continue polluting in the exactly way they are.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me ask you something that just happened in your country while you’re here in Warsaw, Poland, at the U.N. climate summit. Lawmakers, the Venezuelan Congress, has just granted President Maduro the ability to rule by decree for the next year. This has alarmed many inside and outside Venezuela. That means he doesn’t need congressional assent.

CLAUDIA SALERNO: It’s not the first time that happened in Venezuela. Venezuela has a long tradition of, what it is called, I believe, habilitative laws to previous presidents, when you have certain circumstances that needs special handling of—or more rapidity in the way decisions are made. We have the majority in the Congress, so, in principle, it would not be a problem for us as politicians to get whatever law we want in the Congress, because we have the majority. But it’s a special needs that the particular economical situation we are having that needs actually more speed-up actions in certain specific rule. It’s not an open law. It’s actually driven to stop corrupcy and to fight—

AMY GOODMAN: Corruption.

CLAUDIA SALERNO: —strongly against corruption, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Since you were talking about democracy, when it comes to the social movements directing the ministers, especially if you have the majority in the Congress, why he would need these extra powers? Even though, I understand, President Chávez ruled by decree a number of times during his terms.

CLAUDIA SALERNO: And previous presidents, as well, in different moments, since the '50s, I think. It was the first habilitative law that came upon. In principle, he didn't need it. But we need to fight rapidly against that, because the situation is quite critical. And the president is ready to go and to make justice in whoever is doing the wrong things. So he didn’t want it to be in a situation in which, for example, certain—even part of our own process were going to try to protect themselves in their own roles as—in different political situations. So, president is really, really determined to fight against whoever falls, he said—needs to fall. He will not be flexible in that.

AMY GOODMAN: I know you have to leave to meet with the secretary-general, Ban Ki-moon. He’s meeting with leaders of countries who are here, the head of the climate negotiations, to prepare for the September summit in New York. Can you talk about the significance of this?

CLAUDIA SALERNO: It is quite important. I think 2014 is a year, between now and the future agreement, that may be useful to have this opportunity for presidents to get back to the climate agenda, because the last time presidents saw each others to talk about this issue was in 2009, who was, I think, the worst as an area in which presidents were ever in the history of multilateralism.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s when you bloodied your hand.

CLAUDIA SALERNO: Exactly. It was that—

AMY GOODMAN: But why? What was so bad?

CLAUDIA SALERNO: It was that bad. People were not being given the floor to speak. It was that bad. It was quite undemocratic. It was terrible. I mean, every single rule was violated in that meeting. So I think what he is very courage to do—have the courage to do is just to reconvene presidents in a different setting, learning from the previous mistakes, admitting that that was a mistake, and then recalling them, because the issues are still on the table, and we need an agreement. That is a fact.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, Claudia Salerno, what is your assessment of the U.S. role here at the climate talks?

CLAUDIA SALERNO: I am quite surprised to see no role whatsoever. I think that they are again expecting things to go wrong, then to be eased by the fact that the agreement is going to be so hard to have that they may get under the table and just let it pass. But I am hoping that the pushing for hope and agreement was going to be stronger than their concerning quiet voice in this meeting, because they haven’t been talking that much. And that is worrying.

AMY GOODMAN: Claudia Salerno, I want to thank you very much for being with us, lead climate negotiator for Venezuela here at COP 19 in Warsaw, Poland. She is Venezuela’s vice minister of foreign affairs for North America and special envoy for climate change.

When we come back, I had a chance yesterday to question the secretary-general, Ban Ki-moon, as well as the head of the COP 19, the UNFCCC, Christiana Figueres, about the issue of young people being banned for standing with the Philippine climate negotiator and the special role of corporations here at the U.N. climate summit. Stay with us.

Media Options