Related

Guests

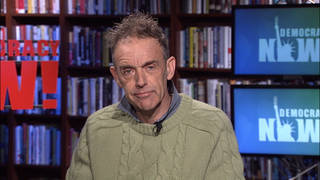

- Dean Harawidower of U.S. Representative Gerry Studds, the first openly gay member of Congress. He is a plaintiff in a lawsuit against DOMA.

The U.S. Supreme Court continues its session on the issue of same-sex marriage, hearing arguments today on the constitutionality of the Defense of Marriage Act. DOMA was signed into law by President Bill Clinton in 1996 and denies federal benefits to legally married same-sex couples. We are joined by Dean Hara, a plaintiff in another lawsuit against DOMA. He is the widower of U.S. Rep. Gerry Studds, the first openly gay member of Congress. Hara reflects on Studds’ decision to come out as a gay man. “I think that, as he demonstrated in that act, it gave a lot of other people the confidence and the courage to also stand up,” Hara said. “And I think that act has brought us where we are today. Less than 50 years after Stonewall, 30 years after Gerry spoke out on the floor of the House, it’s a different world that we live in.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: For the second day in a row, the Supreme Court is confronting the issue of same-sex marriage, hearing arguments today on the constitutionality of DOMA, the Defense of Marriage Act. DOMA was signed into law by President Clinton in 1996 and denies federal benefits to legally married same-sex couples. The law prevents same-sex married couples from filing joint federal tax returns, prevents a same-sex spouse from collecting Social Security survivor benefits. It also prevents federal employees from sharing health insurance and other benefits with a same-sex spouse.

For more, we’re going to Boston, Massachusetts, where we’re joined by Dean Hara, a plaintiff in another lawsuit against DOMA. He is the widower of U.S. Congressmember Gerry Studds, the first openly gay member of Congress.

Dean Hara, welcome to Democracy Now! What do you think your husband would have thought, Congressmember Studds, if he were alive today about this day?

DEAN HARA: I think that he would be surprised that we have made such progress and that this issue is at the Supreme Court 17 years after it was signed into law.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the significance of what we’re about to witness today, the Supreme Court weighing DOMA. By the way, President Clinton did sign it into law and says that he seriously regrets it today. He, in fact, says he had serious concern about signing it at the time he did.

DEAN HARA: Having been there in 1996 during the debate, a number of people—Gerry, myself and a handful of members of Congress—knew that the Defense of Marriage Act was blatant discrimination back in 1996. Unfortunately, at that point, it was really just abstract. No same-sex couples were able to get married anywhere in the entire country. It wasn’t until 2004, when Gerry and I were able to get married in Massachusetts one week after it became legal, that what was abstract became concrete. As you had said earlier, Amy, the Defense of Marriage Act bans any kind of benefit that would come from taxation, Social Security, any other kind of benefit. So at that point, when we got married, it became actual discrimination, where I was—would not be treated the same as any of the other colleagues that Gerry had worked with in Washington.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the Gill v. Office of Personnel Management, OPM, case that, Dean, you’re involved with today, this lawsuit.

DEAN HARA: I am one of 16 plaintiffs in the case that was brought back in March of 2009 to challenge the discriminatory effects of the Defense of Marriage Act. The other plaintiffs represent a broad range of people who are hurt, families where they are unable to get the tax benefits or the health insurance benefits from a spouse. Obviously, it’s a pocketbook issue for all families trying to save money. It also, on the other spectrum—just as Edie Windsor, the plaintiff in the case before the Supreme Court today, I have fellow plaintiffs that had been in long-term relationships. A friend, Herb Burtis, also a plaintiff, was in relationship for 60 years, cared for his partner when he was dying of Parkinson’s, but yet when he passed away, he was denied any of the kind of Social Security safety net that he would have been entitled to had his marriage been recognized by the federal government.

AMY GOODMAN: Dean, what about your own case? What is it that have you been denied?

DEAN HARA: Well, in my case, as you had said, Amy, yes, it is—you said the congressional pension. I look at it more that I—when I first applied for the benefits, I didn’t go, in my mind, as a congressional spouse, but as somebody who had been the surviving spouse of somebody who worked for our country as a federal employee for 25 years. The benefits that I’m seeking are the same as any other surviving spouse of a federal employee, which would include the pension, health insurance, and obviously, as I get older, other kind of Social Security benefits.

AMY GOODMAN: Dean Hara, I want to turn to your late husband, Congressmember Gerry Studds, in his own words. In 1987, he spoke with the Gay Cable Network during a visit to Cincinnati.

REP. GERRY STUDDS: I arrived in Congress in 1973 at the age of 37 without, to my knowledge, ever having met another gay person. There is a long, long, long distance between me in 1973 and my standing here today in 1987. That’s a lot for 14 years. And I think we all—I don’t mean that just my individual situation—I think we all need to keep that in mind. And I also say, with respect to AIDS—you didn’t ask this question, but in the immensity, or notwithstanding the immensity of the tragedy of this epidemic, insofar as one can even remotely look at a silver lining—I say this with great hesitation, because you can’t talk about silver linings in the face of a tragedy of this magnitude—but if there is one, I think it is that the existence of gay men and women is no longer subject to question. Many of us grew up in a world where most people didn’t know there was such a thing, or chose to ignore it, and never saw any reference to ourselves. That is absolutely unthinkable from this point on. I, in all of my life until very recently, never saw a newspaper or heard a television or radio report about gay people that was not totally and thoroughly pejorative and negative. Now, every day, every morning, every afternoon, every evening, every citizen of this nation reads and hears about the existence of gay people. It is now an incontrovertible fact. We can never go back from that. That is an extraordinary step in itself.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that is more than 25 years ago. That was Congressmember Gerry Studds in 1987. Your thoughts, Dean Hara, as you listen to your longtime partner, and your analysis of what this DOMA case means today in the Supreme Court and what you can expect based on what you heard yesterday in the Supreme Court in the challenge to Prop 8 in California?

DEAN HARA: I think what—well, obviously what Gerry was talking about was the progress that was made at this point, but I think that is even more evident today when we look at the national polls, to how the percentage is over 50 percent now of people that say they know a gay or lesbian person, either as a family member, co-worker, neighbor, and the number of people that support same-sex marriage. It is—it’s a great tide that has changed in even the last 10 years. And I think, as Gerry used to always say, the more people that stand up and self-identify—because if you remember, really being gay or lesbian, you have to self-identify; there’s no way to pick somebody out on the street—it makes all of our straight friends and allies also our supporters, because they see how the Defense of Marriage Act hurts people that they know. It’s not an abstract issue for them, either.

AMY GOODMAN: How did Gerry Studds come out in Congress? I mean, we’re talking about this is before Barney Frank, a fellow congressmember from Massachusetts, came out.

DEAN HARA: Right. Gerry was the first openly gay member of Congress. He came out in the midst of a controversy in 1983. I think the most important thing of his coming out, though, was that in the midst of this controversy of—rather than saying that his actions were based on alcohol or any of the other excuses that a number of people, of other members of Congress have used over the years, he proudly stood up in the floor of the House and said that he was a gay man, something that had never been done before. I think that, as he demonstrated in that act, it gave a lot of other people the confidence and the courage to also stand up. And I think that act has brought us where we are today. Less than 50 years after Stonewall, 30 years after Gerry spoke out on the floor of the House, it’s a different world that we live in.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you, Dean Hara, for being with us today, and I want to end with the comments of a legislator, a former legislator in Minnesota. During this month’s hearings in Minnesota on legalizing same-sex marriage, at least one former Republican lawmaker expressed regret for her prior support of DOMA, the Defense of Marriage Act. In a tearful speech, Lynne Osterman implored Minnesota lawmakers to legalize same-sex marriage.

LYNNE OSTERMAN: I cast a politically expedient vote in favor of DOMA, and I have regretted that ever—ever since. It was not my conscience or my own compass. My dad is a retired Presbyterian minister. In fact, he served the congregation that Reverend Chadwick now serves. I’ve heard lots of Bible-based sermons over the years. And never once did I hear that someone else’s love was somehow lesser than the love between my parents of now 55 years. My husband of almost 26 years and I have established and demonstrated our decision-making priorities with our two children, stressing people are more important. It’s never been, “Well, except for those people.” Nothing in my life says it’s OK to treat people differently than how I would want to be treated—fairly, respectfully, equally. And that’s really what this conversation is about. Whether you believe in big government or small, do you believe in fair, respectful, equal? Is it ever OK to say, “Well, except for those people”?

I feel like I’m at the Oscars; I see the red sign.

Lawmakers before us—you—all over this nation have had conversations about equality, respectability and fairness. We’ve all taken our history classes and could come up with our own lists of instances. What were the polls like for those issues? Was everyone ready when our elected officials took the reins and led our communities, state and nation so those laws were changed? Voting no today, this session, might seem politically expedient, but I can tell you from experience that you will have to live knowing that a no vote is not fair, it’s not respectful, and it’s not equal. I blew my vote, and I’m imploring you, please get this right. Minnesota citizens just want you to lead.

AMY GOODMAN: Former Republican Minnesota lawmaker Lynne Osterman, speaking before her former colleagues. And I also want to thank Dean Hara for having joined us, plaintiff in the DOMA lawsuit, widower of the late Congressmember Gerry Studds, the first openly gay member of Congress.

This is Democracy Now! When we come back, we’re going to Bismarck and Fargo, North Dakota. North Dakota has just enacted the strictest abortion ban in the country. Stay with us.

Media Options