Related

Guests

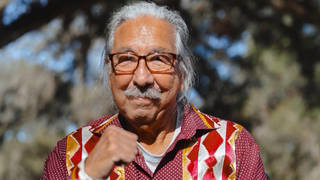

- Bill McKibbenco-founder and director of 350.org. He is author of Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet.

ExxonMobil continues its cleanup efforts after a ruptured pipeline sprayed thousands of barrels of crude oil from Canada across a central Arkansas subdivision, forcing nearly two dozen homes to evacuate. The 20-inch so-called “Pegasus” tar sands pipeline burst late Friday near Mayflower, Arkansas, creating what the Environmental Protection Agency is categorizing as a “major spill.” The incident is refueling calls for the Obama administration to reject the controversial Keystone XL pipeline, which would deliver tar sands oil from Canada to refineries in Texas. “It’s almost as if nature was trying to send a message that it might be best to just leave this stuff underground in Canada, where it’s been safely for the last few million years, instead of trucking it, piping it, training it hither and yon across the countryside,” says Bill McKibben, co-founder and director of 350.org. He is author of “Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet.” [includes rush transcript]

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: ExxonMobil continues cleanup efforts after a ruptured pipeline sprayed thousands of barrels of crude oil across a central Arkansas subdivision, forcing nearly two dozen homes to evacuate. The 20-inch so-called “Pegasus” tar sands pipeline burst late Friday near Mayflower, Arkansas, creating what the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, is categorizing as a “major spill.”

Officials say the pipeline gushed oil for 45 minutes before being stanched. More than 12,000 barrels of oil and water have been recovered. According to Exxon, the pipeline will be excavated as part of its investigation to determine the cause of the leak. ExxonMobil says about 50 claims have been filed so far by people affected by the oil spill. Local news station KTHV 11 spoke to two Mayflower residents impacted by the spill.

MAYFLOWER RESIDENT 1: You know, we’re all having to pay mortgages, and we can’t even live in our houses or—you know, basically, if it doesn’t fit in our car, we don’t have it right now. So, we’re really concerned about that, and we’re just concerned about our property values. And what is ExxonMobil going to do for us?

MAYFLOWER RESIDENT 2: I had no idea that there was a pipeline out here, I mean, literally right at the corner of the subdivision. Supposed to be a 20-inch pipeline, run from Illinois to Texas. I don’t know.

AMY GOODMAN: ExxonMobil confirmed the pipeline was carrying western Canadian Wabasca Heavy crude at the time of the leak. According to Inside Climate News, this type of crude oil is especially difficult to clean up when it spills into water. Efforts are currently underway to prevent the oil from contaminating the nearby drinking source, Lake Conway.

The spill is refueling calls on the Obama administration to reject the controversial Keystone XL pipeline. The proposed 1,700-mile pipeline would deliver tar sands oil from Canada to refineries in Texas.

For more, we go to Bill McKibben, co-founder and director of 350.org, author of Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet. We did invite ExxonMobil on the air; they declined.

Bill, can you talk about the significance of this spill?

BILL McKIBBEN: Well, one thing to bear in mind is, when we’re thinking about this—whether or not to approve this Keystone pipeline, the pipe that just burst in Arkansas carries less than a tenth of the amount of this heavy tar sands crude that Keystone would. It’s about 80,000 barrels a day, not 900,000 barrels a day. So, multiply the pictures you’re seeing from Arkansas by 10, and then, of course, transpose them on top of the Ogallala Aquifer—not a pretty picture in any way.

Also, of course, the Pegasus pipeline, just like the Keystone pipeline, was touted for having the latest and most advanced leak-detection technology, and on and on and on. This is just one more sign of what a misbegotten adventure this whole tar sands thing is. There’s an tremendous op-ed piece in New York Times today from the Canadian writer Thomas Homer-Dixon, pointing out that a plurality of Canadians oppose this pipeline and are eager to get rid of the whole tar sands business. You know, this is—this is a disaster not waiting to happen; it’s a disaster happening in slow motion. And the only question is whether the Obama administration and the Kerry State Department are going to go along with it or not.

AMY GOODMAN: ExxonMobil did release a statement that read in part, quote, “Emergency response efforts are focused on ensuring the safety of the community members and the response workers, addressing community concerns and the cleanup process. Precautions are in place to keep oil away from Lake Conway,” they said. Bill, how has ExxonMobil’s response to the spill compared to last ones?

BILL McKIBBEN: Well, this is in a—this is in a different place. It’s more—you know, it happened right in the middle of a subdivision, apparently. There’s almost unbelievable pictures of what people’s backyards look like. I just put some up on my Twitter feed. The last huge spills that happened were in Kalamazoo, Michigan, where the Kalamazoo River is still—parts of it still shut down for human use two or three years later, and in the Yellowstone River.

The trouble with this stuff that’s spilling out of the—I mean, it would be bad enough to have a regular oil spill, right? We remember the Exxon Valdez, on and on and on. This stuff’s a whole degree of nastiness worse. It’s this—it’s called “dilbit,” diluted bitumen. It’s the tar sands. You have to heat it up, and then you have to add chemicals to even get it to flow. When it comes out of the pipe, it’s incredibly hard to clean up. You know, couple that and the fact that burning this stuff, as Jim Hansen at NASA put it, on top of everything else we burn, means “game over for the climate,” and you see that we’re kind of messing with the environment on so many fronts that it’s—I mean, it’s as if you had set out to figure out what was the worst environmental thing you could do.

AMY GOODMAN: Bill, the Mayflower spill comes two days after a train also carrying Canadian crude derailed in Minnesota, spilling, what, something like 15,000 gallons of oil.

BILL McKIBBEN: Yeah, it’s almost as if nature was trying to send a message that it might be best to just leave this stuff underground in Canada, where it’s been safely for, you know, the last few million years, instead of trucking it, piping it, training it hither and yon across the countryside. You know, this is the kind of thing that people will look back on in 20, 30, 40 years and say, “What part of this didn’t you get? Why didn’t you do what Germans did and go straight to sun and wind? You know, why didn’t you take the steps that are—instead of prolonging for a few more years the absolute bottom-of-the-barrel dirtiest energy policies that you could find?”

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, Bill, we just have a minute, but you talked about this coming as the Obama administration is making a decision about Keystone XL. Where does that stand right now? What do you understand both President Obama and Secretary of State Kerry are deciding at this point?

BILL McKIBBEN: Over the next 15 days, there will be a big push to get public comment into the State Department on their preliminary environmental impact statement, an environmental impact statement that said nothing like what happened in Arkansas was actually likely to happen. We’re hoping we can get a million comments in. If people will go to 350.org, they’ll find some ways in order to help out with this process. You know, the power of the fossil fuel industry in Washington is enormous. They have all the money. The only thing we can stack up on the other side is the power of movements. We’ve been building them as fast as we can. We’ve had the largest civil disobedience action in 30 years about anything, about this pipeline. We had 40,000 people on the Mall last month in D.C. in the largest climate rally ever. I don’t know if it’s going to be enough, but we’re fighting it as hard as we can, Amy.

AMY GOODMAN: Bill McKibben, I want to thank you for being with us, co-founder and director of 350.org.

Media Options