Guests

- Sonia Sanchezrenowned writer, poet, playwright, activist, and one of the foremost leaders of the black studies movement. She is the author of over a dozen books. Sanchez is Philadelphia’s poet laureate. She’s a longtime friend and colleague of Amiri Baraka.

- Felipe Lucianopoet, activist, journalist and writer. He knew Amiri Baraka for 43 years. He co-founded the Young Lords and was an original member of the poetry and musical group, The Last Poets.

- Komozi Woodardprofessor of history at Sarah Lawrence College. He is the author of A Nation Within a Nation: Amiri Baraka and Black Power Politics.

- Larry Hammchairman of the People’s Organization for Progress in Newark, New Jersey. He was named Adhimu by Amiri Baraka.

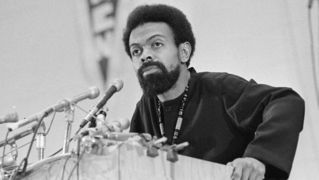

Watch this online-only extended interview on the life and legacy of Amiri Baraka, the poet, playwright and political organizer who died Thursday at the age of 79. We talk to four of his friends and play some more of Amiri Baraka in his own words.

Watch Part 1 of this interview: Amiri Baraka (1934-2014): Poet-Playwright-Activist Who Shaped Revolutionary Politics, Black Culture

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: We are continuing our special on the life and legacy of the poet, playwright, and political organizer Amiri Baraka. He died on Thursday in Newark, New Jersey, at the age of 79. Baraka was a leading force in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

And to talk more about Amiri Baraka’s legacy, we’re joined by four guests. In Philadelphia, Sonia Sanchez us, the renowned writer, poet, playwright, activist and one of the foremost leaders of the black studies movement. She’s the author of over a dozen books, including Morning Haiku, Shake Loose My Skin and Homegirls and Handgrenades. Sanchez is a poet laureate of Philadelphia and a longtime friend and colleague of Amiri Baraka.

And here in the studio, we’re joined by three guests: Felipe Luciano, poet, activist, journalist and writer. He knew Amiri Baraka for 43 years. He’s a former chairman of the Young Lords and was an original group of the poetry and musical group The Last Poets.

Komozi Woodard is a professor of history at Sarah Lawrence College, the author of A Nation Within a Nation: Amiri Baraka and Black Power Politics.

And Larry Hamm is with us, chairman of the People’s Organization for Progress. He was named Adhimu by Amiri Baraka. And you were talking about names—

LARRY HAMM: Yes.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —just when we were on break, Larry. Could you—

LARRY HAMM: Well, just a little—you know, I don’t want to get metaphysical, but… Baraka gave me the African name Adhimu in March of 1972. I asked him for it after attending the National Black Political Convention.

AMY GOODMAN: What was that convention, that he helped organize?

LARRY HAMM: Well, that was probably one of the most historical events in contemporary African-American history. Thousands of delegates were elected from all 50 states to attend the National Black Political Convention, which was co-convened by Congressman Charles Diggs from Detroit, by Mayor Richard Hatcher of Gary, Indiana, and by Amiri Baraka. And I would say—and maybe Komozi can critique it—I would say that Baraka probably was at his peak of political influence during the Gary convention. And I can remember what an uplifting experience it was for me, because I had come under vehement condemnation as a school board member because I had made a motion—

AMY GOODMAN: A school board member at the age of 17.

LARRY HAMM: Yes, yes—that students should be able to bring in the red-black-and-green flag to their classroom.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Oh, no, you didn’t.

LARRY HAMM: Oh, yes, I did.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Oh, no, you didn’t.

LARRY HAMM: And when I got to Gary for the National Black Political Convention, Dick Hatcher had red-black-and-green flags flying from every street streetlamp.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Oh, my lord.

LARRY HAMM: So it was enlightening for me. But I had asked Baraka for an African name after that, and he gave me the name Adhimu Chunga, which means “exalted youth.” But many years later, at the age of 44, I learned that I was adopted. And I have since met my birth mother. And my birth name, I found out at the age of 44, was Anthony LeRoi Burton [phon.].

FELIPE LUCIANO: Isn’t this something?

AMY GOODMAN: So, Sonia saying you have the eyes of Amiri Baraka might not be so far off.

FELIPE LUCIANO: I’m telling you, there’s something—there’s something going on here. He’s got Amiri’s eyes.

LARRY HAMM: It’s scary. It’s scary. It’s scary, right?

KOMOZI WOODARD: He was prolific.

AMY GOODMAN: But let’s let Sonia get a word in there.

SONIA SANCHEZ: I think—I think what you’re saying is that we all, at some time in our lives, have had the eyes of LeRoi, Brother Baraka. You know, I think that’s really relevant, you know, because he made us see what we were not seeing at some particular point. He made us take a second look, a second glance. He made us say, “Come on, you’re not really using that intellect. You know, you know there’s got to be something better than what we’ve got here.”

And so, yes, I’m sure you had those eyes and that name, LeRoi, because we understand that—you know, the joy of having met Brother Baraka was that I was—had graduated from Hunter and was going to NYU doing some grad classes and trying to get a degree, and I studied with Louise Bogan. And after I studied with her and I got published for the first time in her class, we met in the Village on Charles Street, a bunch of us, and one day—we would go down to one of the jazz places there in the Village. And one day we walked in, and someone said in the group, “That’s LeRoi Jones!” And I said, “Yes.” Well, I’m an ex-stutterer, so I walked behind, and this voice said, “Sanchez!” And I jumped, and I literally jumped and turned around. He said, “Send me some of your poetry. I’m doing a journal out of Paris, France.” And I said, “Y-y-y-y-y-y-yes.” And I went and sat down. The stutters came out. And they said, “Oh, oh, you’re going to do that.” I said, “Oh, no. I mean, he doesn’t want my poetry.” Three weeks later, we come back into the Blue Note. He’s sitting there drinking a boilermaker, smoking the French cigarettes. And he says, “I guess you don’t want to be in the journal, huh, Sanchez.” And I said, “You were serious?” And he said, “Yes.” I jumped in my Volkswagen, drove up the West Side Highway in five minutes to my Riverside Drive apartment, pulled down my Olivetti, typed up some poems, came back out that night, took it down to the post office that night. Three weeks later, he’s sent me a letter: “Dear Sonia Sanchez, Yeah!” Just “Yeah,” that’s all. Just “Yeah,” exclamation point, you know?

And the point is that the joy of that, this person—you know, we—as a professor for 40 years, right, and as a person involved with the Black Arts, you know, Movement also, too, the joy was that we taught, and every place we go, we have—we have students. You’re with Brother Baraka, and people come up and say, “Oh, remember? I was in your class, right?” You know, people come up to me, “You remember? I was in your class.” And you don’t always remember the faces, or you do, but you remember the names, or you don’t. But what we are saying, 40 years of being involved with activism and teaching in universities and teaching from the stages of America, all of these are our children. They have all our eyes. And they have Brother Baraka’s eyes. I mean, he has shown young people how to look at the world, you know. This is this man, you know, who showed us exactly how to remove the garbage out of our eyes and our lives and how to be human.

FELIPE LUCIANO: And to that end—

AMY GOODMAN: Felipe Luciano.

FELIPE LUCIANO: I’d like to add that his African aesthetic, his Black Arts Movement basically said this: You don’t need to validate yourself by Western liberal ideas. We hear music differently. Our auditory nerve is different. Our optical nerve is different. And so, to sit with him, for example, and listen to Freddie Hubbard, to sit with him and listen to Trane, Sun Ra, to listen to a Grady Tate, to—he loved Ellington—one would think that with his advanced sense of harmonics, with his advance sense of improvisation, he would be into Anthony Braxton. But he loved the classics. He loved tradition. And not only that, but he loved inclusion. And so, Miguel Algarín, who was his contemporary at Rutgers University, he’s directly responsible. He’s the foment of the Nuyorican poets. Imagine, this guy, brought up in Newark, who gave us an entire encyclopedia on American poetry and told us to take the stuff that was in front of our eyes and make it into poetry. Tato Laviera, Miguel Piñero, all of these people who have now passed on, are a result of Amiri Baraka, not to mention myself.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Felipe, now, you’re talking about his relationship to music. And in August of 2007, Amiri Baraka spoke at the funeral for another legendary figure, jazz drummer Max Roach, at Riverside Church in New York City. Let’s listen to what he said about Max Roach.

AMIRI BARAKA: I wrote a poem for Max on his seventy-fifth birthday. This is a picture of Max and I in Paris. And this is called “Digging Max.”

(At Seventy Five, All The Way Live!)

Max is the highest

The outest the

Largest, the greatest

The fastest, the hippest,

The all the way past which

There cannot be

When we say MAX, that’s what

We mean, hip always

Clean. That’s our word

For Artist, Djali, Nzuri Ngoma,

Senor Congero, Leader,

Mwalimu,

Scientist of Sound, Sonic

Designer,

Trappist Definer, Composer,

Revolutionary

Democrat, Bird’s Black Injun

Engine, Brownie’s Other Half,

Abbey’s Djeli-ya-Graph

Who bakes the Western industrial

singing machine

Into temperatures of syncopated

beyondness

Out Sharp Mean

Papa Joe’s Successor

Philly Joe’s Confessor

AT’s mentor, Roy Haynes’

Inventor, Steve McCall’s

Trainer, Ask Buhainia. Jimmy Cobb,

Elvin or Klook

Or even Sunny Murray, when he aint

in a hurry.

Milford is down and Roy Brooks

Is one of his cooks. Tony Williams,

Jack DeJohnette,

Andrew Cyrille can tell you or

youngish Pheeroan

Beaver and Blackwell and my man,

Dennis Charles.

They’ll run it down, ask them the next

time they in town.

Ask any or all of the rhythm’n.

Shadow cd tell you, so could

Shelly Manne, Chico Hamilton.

Rashid knows, Billy Hart. Eddie

Crawford

From Newark has split, but he and

Eddie Gladden could speak on it.

Mtume, if he will. Big Black can

speak. Let Tito Puente run it down,

He and Max were tight since they

were babies in this town.

Frankie Dunlop cd tell you and he

speak a long time.

Pretty Purdy is hip. Max hit with

Duke at Eighteen

He played with Benny Carter when he

first made the scene. Dig the heavy learning that went with

that. Newk knows,

And McCoy. CT would agree. Hey,

ask me or Archie or Michael Carvin

Percy Heath, Jackie Mc are all hip to

the Max Attack.

Barry Harris can tell you. You in

touch with Monk or Bird?

Ask Bud if you see him, You know he

know, even after the cops

Beat him Un Poco Loco. I mean you

can ask Pharaoh or David

Or Dizzy, when he come out of hiding,

its a trick Diz just outta sight.

I heard Con Alma and Diz and Max

In Paris, just the other night.

But ask anybody conscious, who Max

Roach be. Miles certainly knew

And Coltrane too. All the cats who

know the science of Drum, know

where our

Last dispensation come from. That’s

why we call him, MAX, the ultimate,

The Furthest Star. The eternal

internal, the visible invisible, the

message

From afar.

All Hail, MAX, from On to Dignataria

to Serious and even beyond!

He is the mighty SCARAB, Roach the SCARAB, immortal as

our music, world without end.

Great artist Universal Teacher, and

for any Digger

One of our deepest friends! Hey MAX!

MAX! MAX!

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Amiri Baraka delivering a poem about the jazz pioneer Max Roach. Baraka wrote Max Roach’s biography. I want to talk, Komozi, about the—we were talking earlier about names, and Amiri gave you a name, as well. Your—could you talk about that?

KOMOZI WOODARD: Oh, yeah. I was named Komozi in the movement there. That was a part of the process, is you applied for a name. I wanted a name—I put down that I wanted to liberate black people.

LARRY HAMM: Wow!

KOMOZI WOODARD: And I forget what that name would have been in Swahili.

LARRY HAMM: And how old were you when you said that you wanted to liberate—

KOMOZI WOODARD: I think I was 18 or 19. So—

AMY GOODMAN: Where were you born, Komozi.

KOMOZI WOODARD: Newark, New Jersey, yeah. And instead, he gave me a spiritual name, which is Komozi, which is “redeemer.” So I’ve been trying to live up to that part of it for a long time, but I guess he saw that in me, that I needed to work on my spiritual development.

AMY GOODMAN: How did Amiri react to you writing a biography about him?

KOMOZI WOODARD: It’s a funny story. Now, he asked for two boxes of the books. And the next thing I heard, he was selling them on street corners. So I guess that’s—

FELIPE LUCIANO: Komozi, you know that he studied—he started in philosophy and religion.

KOMOZI WOODARD: Yeah.

FELIPE LUCIANO: And quiet as it’s kept, he was much more—

AMY GOODMAN: Felipe.

FELIPE LUCIANO: —spiritual than people give him credit for.

KOMOZI WOODARD: Oh, yeah. Well, when I—

SONIA SANCHEZ: Oh, no, he had a spirituality in his poetry.

KOMOZI WOODARD: Baraka used to have this tiny—

AMY GOODMAN: Let Sonia Sanchez have a word in here, from Philadelphia.

KOMOZI WOODARD: Sorry, OK.

SONIA SANCHEZ: No, I said—no, I don’t think that anyone is surprised at his—I mean, you hear the spirituality in his poetry, and you hear it, you know, when he speaks. He might be hip, you know, in that hip way, that New York hip way that we happen to be, but in the midst of all that, you know, you hear the softness and the spirituality and the learning, because he was always studying and learning. He was always bringing some new way of looking at the world, some new philosopher. He would bring—Malcolm did that. You know, when we went to hear Malcolm speak, we took notebooks with us. You know, we took notes, because he always brought something for us to learn. And we would go to the Schaumburg and research this. But Baraka did the same thing, my dear brothers and sister. He always came, and you felt that spirituality, because he would like—in a sense, like Malcolm did, he would raise you up to say, “Yeah, Max!” and at the end, you would say, “Max, Max, Max, Max, Max.” It was the loud and the soft, you know, because it was the blues in there, but it was always the sermon in there also, too. It was always that amazing music that he brought to his work, to his poems, to his speeches. Always we heard the music, and the music was doo-dat-doo-dat-doo-doo-doo, doo-dat-doo-dat-doo-doo-day, doo-dat-di, doo-dat-di, doo-doo-di, doo-doo-di, you know. And you would—you lean back on your eyes, and you say, “Yeah, man.”

FELIPE LUCIANO: Listening to music with Amiri Baraka was like watching another concert.

AMY GOODMAN: Felipe.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Last year, we went to the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, Juan, and I’m sitting there with Christian McBride and Terry Blanchard, two of the most incredible bassist and trumpet players. And we were sitting there, and we were talking and laughing so loud. Amina turns around and says, “Why don’t you all shut up?” because Amina was always putting us—you know, come on. We went to hear—

AMY GOODMAN: Amina is Baraka’s wife.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Amina is his wife. So, we would go—so, we went to the Lenox Lounge, for example, to hear Hilton Ruiz, may he rest in peace. And Hilton Ruiz, a great Puerto Rican pianist—

SONIA SANCHEZ: Yeah, yeah.

FELIPE LUCIANO: —was vamping octaves on both hands exquisitely, exquisitely, because one can do the vamp, but to hear each separate note—and he jumped up and screamed, “Go, Hilton!” And I jumped up and screamed, “Go!” And she said, “Y’all better sit down, because we’re going to get thrown out this place.” At which point a guy comes up to Amiri and says something surly. You know, Amiri was always listening.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Right.

FELIPE LUCIANO: You couldn’t just throw some sotto voce stuff at him and him not hear it. He said, “What did you say?” You know, with those eyes, because he always looked at you from under his eyes.

LARRY HAMM: Yeah.

FELIPE LUCIANO: He said, “What did you say?” He said, “Let’s go outside.” I said, “Amiri, let’s not get busted tonight.”

LARRY HAMM: Well, along those lines, Felipe—

AMY GOODMAN: Larry Hamm, Adhimu.

LARRY HAMM: —let me just say, when I was at the hospital the night before last—I actually started going up to the hospital, I think it was either before Christmas, and I was also there on Christmas Day and a couple of times after that. Amina and Ras, his sons—Baraka had many children, and they had as—and I guess I’m at liberty now to say, you know, from the point that I saw him, he was not conscious. The family had hoped that the situation was going to turn around.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Yes.

LARRY HAMM: But to help the situation turn around, they had jazz playing in the hospital bedroom, man.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Absolutely, right next to him.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Yes, yes.

LARRY HAMM: And I don’t mean soft, either.

FELIPE LUCIANO: No, no.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Yes, yes.

LARRY HAMM: They had John Coltrane.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Yes. Ellington.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Yes.

LARRY HAMM: They had Pharoah Sanders.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Yes.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Yes.

LARRY HAMM: And you want to hear something that’s really deep? The last night I went to the hospital, which was Tuesday night, Tuesday night, last night I went to the hospital, some folks came in from Bethany Baptist Church. And one of the brothers must be an operatic singer. He stood by the bedside of Amiri Baraka and sang “Ol’ Man River.”

FELIPE LUCIANO: Oh, no.

LARRY HAMM: And with the words that Paul Robeson used.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Paul Robeson, oh, my god.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Oh, my lord!

LARRY HAMM: And it was so deep, because the hospital people was running around, running around, but they didn’t stop him. They just closed the hospital room door and let him finish.

But I want to go back to an earlier point about Amiri’s move to the left and how other black leaders responded. I can remember—I’m not quite sure; I believe it was ’72 or ’73, that Amílcar Cabral died. Amílcar Cabral was the leader of PAIGC.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Right.

FELIPE LUCIANO: January ’73.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Portuguese Guinea-Bissau.

LARRY HAMM: January ’73—that fought the Portuguese and liberated Guinea-Bissau. Amiri Baraka was probably the only African American that was invited to speak at the funeral of Amílcar Cabral.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Right.

LARRY HAMM: And I remember him coming back, and one of the things he was talking about was how many white people were at, you know, the funeral of Cabral. And so, there was, I believe—even before then, there was this tension going on between our black nationalist beliefs and perspectives and what was happening in the real anti-colonial struggle. And I think that goes back, because there was another great event in 1972 beside the National Black Political Convention, and that was African Liberation Day.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yes, yes.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

LARRY HAMM: In 1972. As early as then—and we have to put everything in context. Baraka wasn’t the only one moving left.

SONIA SANCHEZ: That’s right.

LARRY HAMM: The black movement, in parts of it, were moving left. And maybe in one way, Baraka was responding to it, and maybe he was moving in his own time, too. But as early as 1972, people were beginning to question, because, you know, things—we had this very, you know, basic belief that if we simply got the white folks out of office and put the black folks in office, that everything would be all right. And it didn’t work out like that. In fact—

SONIA SANCHEZ: No, no.

LARRY HAMM: —the struggle between Baraka and Gibson began almost after Gibson—

SONIA SANCHEZ: Right, right.

AMY GOODMAN: Gibson, the first black mayor of Newark.

LARRY HAMM: The first African-American mayor that Baraka helped to get elected.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Yes, yes, yes.

LARRY HAMM: You know, that struggle broke out almost immediately, over the appointment of a black police director. Police brutality was one of the main problems that black people face and one of the planks that came out of both the Black Power Convention at West Kennedy Junior High School and the Black and Puerto Rican convention that followed that would be the appointment of a black police director. And Gibson didn’t do that. And, you know, Gibson still might remember. I’m saying, as a matter of record, he didn’t do that. He appointed John Redden, who was a white police director.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Yes.

LARRY HAMM: So the struggle began to sharpen up even then. So—

FELIPE LUCIANO: And the contradictions tightened.

LARRY HAMM: Right, and the contradictions. So, let me fast-forward to 1974. Baraka openly begins to espouse Marxism, Leninism, Mao Zedong thought, and it was not initially well received. And it’s also important to say—and Komozi is a historian; he can correct me on this—but the organization was in decline, as—by 1974.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Right.

LARRY HAMM: Many advocates were leaving on—of their own accord. And then, I’m going to tell you, a lot of people in the community—I’m talking about the regular people; I’m not even talking about the leadership, who condemned Baraka for going to the left—but even a lot of people in the community could not understand it. I remember at one point in the headquarters, where we had had the giant pictures of the black leaders up, they came down, and Marx was up and Engels was up and Lenin was up. And, you know, it happened so fast for some folks that they couldn’t quite keep up.

FELIPE LUCIANO: They couldn’t adjust.

LARRY HAMM: And so, it was a tough—it was a tough road to hoe at that time.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Right.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Well, remember, Komozi and Larry—

AMY GOODMAN: Felipe Luciano.

FELIPE LUCIANO: We’ve had—the black community has had an antipathy toward communism and progressive socialism since the '30s. Amiri would explain to me what happened. If you take the land question out—remember, that was the whole thing: Do we have land? And when the communists came to Harlem in the ’30s, their problem was that they didn't want to admit to racism, institutional racism. And that was a real problem for black folk. Either we deal with the Emmett Tills, or we’re not going to join you. For Amiri to embrace socialism, when the Black Christian Church—remember, they influenced us a lot. The Pentacostals and the evangelicals influenced so many black folk, and Puerto Rican folk, I would add. And they went—they were capitalists. They were involved. They were immersed in a system that was giving them money. Amiri decided, let us not use race as a criteria for evaluation; let’s begin to use class. Unreal. People just couldn’t handle it, because the black middle class didn’t want to admit it. The black middle class did more to criticize Amiri Baraka than any other class, including white folks. They did everything they can to make him mediocre. It never worked.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And in terms of that, though, I think the—he did follow the trajectory of other great leaders who faced a similar kind—at the time, attempts to isolate them—Paul Robeson—

KOMOZI WOODARD: Oh, yeah.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: —also Mandela himself, in terms of his trajectory. And in that sense, he really was among the foremost revolutionaries of the African-American community in the United States.

KOMOZI WOODARD: Well, let’s look at—

AMY GOODMAN: Komozi Woodard.

KOMOZI WOODARD: There are different—there are different arenas that Baraka was operating in. One, he was in the international arena. Many of the African leaders—let me—this issue of the fast move that happened in '74, ’75, here's what happened. I was on the executive meeting at the time. We were supporting a number of different groups in Angola. One of the groups, very embarrassing, that we were supporting turned out to be a CIA front, which was UNITA.

LARRY HAMM: Savimbi.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Savimbi.

KOMOZI WOODARD: Savimbi. Right? When we found that out, then—and he was using the brand “cultural nationalism.”

LARRY HAMM: Yes.

KOMOZI WOODARD: OK? So, that’s why it looked like we made a very quick knee-jerk reaction at the point to say, “OK, we’re going to go for standard Marxism,” at that time, because we saw that the CIA was going to use the brand of cultural nationalism, and they were going to do the same thing to split the struggle in South Africa, try to get the Zulus to cultural nationalists against the ANC. So, that was the change we were responding to, and it—so, for the outside world, it looked like a very quick move. We had been studying socialism for a long time. Let’s remember, Baraka was in Cuba in 1960.

FELIPE LUCIANO: That’s right.

KOMOZI WOODARD: Right? He was in Cuba in 1960. There’s a funny story about this. Baraka at the time was a wild kind of a party person. And so, the party was always in his room, and everybody’s drinking in the room. So, they came with the bill for the drinks, and Baraka takes it and says, “Charge it to the revolution.” So that’s—Harold Cruse told me that story.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the effect of Cuba on LeRoi Jones, Amiri Baraka, the effect on his poetry, the “Cuba Libre” essay.

KOMOZI WOODARD: It’s a transformative moment. It’s similar to Paul Robeson’s transformation in the Spanish Civil War, when he, you know, had to take the side against slavery. Baraka is confronted by young poets from Latin—all over Latin America who are politically engaged. And because of the Cold War, we separated culture, art and politics. Right? And he saw that they basically embarrassed him and said, “How could you not be involved in the struggle for your people?” And so, he came back, and I think that’s when he joined a lot of these things and started really thinking seriously. And I think, you know, the cultural thing was what—about the Cold War, the Cold War really made it taboo for black people to express their real feelings.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Yes, sir.

KOMOZI WOODARD: So, even as a poet, I think he was struggling against this, is—you know, this whole—how can I—why am I not permitted to have my own feelings in my poetry? Like the Cold War kind of deadened that. So, it both culturally and politically came out of that, and I think seeing the Latin American example was very powerful for him.

AMY GOODMAN: I also wanted to follow up on Juan’s question about South Africa and Mandela. I mean, Adhimu, Larry Hamm, you went from Newark, the youngest member of the school board, deeply influenced by Amiri Baraka, named by him—

LARRY HAMM: Deeply.

AMY GOODMAN: You go on to Princeton, and you become a leader of the anti-apartheid movement there, taking on the corporation—that’s Princeton University—and their investments.

LARRY HAMM: Yes, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about Nelson Mandela and how Amiri Baraka influenced you and the similarities there.

LARRY HAMM: Well, the whole struggle that was going on in Africa, I became acquainted with through Amiri Baraka. Baraka had and the Committee for a Unified Newark had several headquarters and properties in Newark. One, of course, was known as 502 High Street. That was Hekalu Umoja, the House of Unity. That’s where I first had my first meeting with Amiri Baraka, on the third floor of that building. But right next to Hekalu Umoja was his store. They had a store, Nyumba Ya Ujamaa, the House of Cooperative Economics. And it was at Nyumba Ya Ujamaa that I bought my first books about Kwame Nkrumah. I bought Return to the Source, Amílcar Cabral. All the revolutionary leaders from there, they sold—

AMY GOODMAN: Kwame Nkrumah, the founding president of Ghana.

LARRY HAMM: That’s right, of Ghana. All the revolutionary leaders of Africa, Baraka had their books on sale there. My first Malcolm X record, I bought from Nyumba Ya Ujamaa. So, the struggle in South Africa, although I had heard about it, it was really through Baraka, and not just the books. Every Sunday, Baraka and the Committee for a Unified Newark had something called “soul session.”

FELIPE LUCIANO: Yes, I remember.

LARRY HAMM: At 3:00 on Sundays. And I believe they were first at Hekalu Umoja, and then when he got Hekalu Mwalimu, which is Temple of the Teacher, 13 Belmont Avenue, the soul sessions were there. And that’s where Baraka would really teach, you know, teach politics. You know, that’s how I felt as a young person. I don’t know how the other fellows felt. But as a young person, I was sitting there in awe. And every Sunday, he would talk about the struggles here at home, he would talk about the struggles in Africa, you know, and he would teach us. And it was there that I first really learned about the struggle in South Africa.

So, when I got to Princeton, I was already a member. I had been on the school board. I was accepted at Princeton and went to Princeton in 1971. But like Baraka, I left Princeton to do my three-year term on the school board, and then returned back to Princeton. So I returned back with a much higher level of political consciousness. So, it was—

AMY GOODMAN: Were you there around the time of Michelle Obama?

LARRY HAMM: I was there long before Michelle Obama. The second time—I graduated from Princeton, finally, in 1978. But the struggle in South Africa began to intensify, and our first campaign at Princeton was to get the banks at Princeton on Nassau Street to stop selling the Krugerrand. The Krugerrand was the gold coin that South Africa was using to raise a lot of money. And then, you know, we began the struggle for disinvestment, which had—for divestment, which had broken out on other campuses even before Princeton, at Stanford and other places. In fact, the first event that we had, we didn’t even—it wasn’t even an ANC. This is where the—I’m still influenced by the black nationalist movement.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: The PAC. That’s the PAC.

LARRY HAMM: The first—the first representative we brought to Princeton was from the PAC.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Right.

LARRY HAMM: The Pan Africanist Congress. We brought him first, so we had a kind of relationship with the Pan African Congress, and then we met Prexy Nesbitt and other people from the American Committee on Africa. And then we began to move closer to them, and we brought delegates from the ANC. We brought delegates from ZANU, Tapson Mawere, from ZANU. So we were not just talking about divestment, Princeton divesting; we were educating the students on the campus about the anti-colonial struggles, including the struggle against apartheid on that campus. So, like I said, I came back to Princeton with a consciousness that lent itself toward that activity.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking about the life and legacy of the poet, of the activist, of Amiri Baraka, who died on Thursday in Newark, New Jersey, Newark where he was born. I want to go back to a clip of Amiri Baraka speaking in June 2004 at the first National Hip-Hop Political Convention right there in Newark. He talked about the need to defeat President George W. Bush and much more.

AMIRI BARAKA: I don’t have a whole lot of time. I just want to say something. Why is this in Newark? Why is it in Newark? 1970, the Black and Puerto Rican Convention brought the blacks and Puerto Ricans together. If you think electoral politics doesn’t make any difference, you’re being shortsighted. If you’re not registered to vote, you’re a fool. If you don’t vote, you’re worse than a fool.

Why conventions? Because we have to organize ourselves because we are slaves. We want conventions so we can build a stable national political organization, not because we are separatists or because we know we are not separate. We must elect our own candidates. For instance, why do you think this is in Newark? The Gary convention was where? Gary. Why? Because it had a black mayor and black police chief. This is here because, of all these cities, Newark since 1970 has had a continuous political power, exercised by, well, at least Negroes, if they ain’t black.

But the point is this: Black Power is not paradise; it is a higher form of struggle. Once you organize yourself and elect people that look like you or represent your interests in your town, then you’re going to have to fight with them. Nobody is telling you that this is all. That’s why I’m saying, I’d rather beat Bush than talk bad about my man. You understand? I’d rather beat Bush and you say, “[bleep] Bush” and “[bleep] Kerry.” Yeah, that’s good. “[Bleep] Bush” and “[bleep] Kerry.” But you’ve got to beat Bush, or you won’t even be here to fight Kerry. You understand? You have to beat Bush. Look, don’t nobody—look here, you might be the strongest person in the world, but if you get sick, you’ve got diarrhea or some other trots, but if you get sick like that, you’re going to have to stop the sickness. Bush is killing us. You understand? He is transforming this society into fascism. You know what fascism is, really, the rule—the naked rule by force. The naked rule by force.

Now, what we were saying, Malcolm X said the ballot or the bullet. Charles Barron, my man, he was in the Black Panthers; I was in the Congress of African People—understand?—who, when we got old enough to get our heads beat long enough, decided, just like Malcolm X told me the month before he died, and just like Martin Luther King told me the week before he died, in my house, said, “What we must have, Brother Baraka, is a united front.” We must build that united front, no matter whether you’re the Panthers, the cultural nationalists, whether you believe in rap or whether you believe in hip-hop, whether you’re a Muslim or a Christian, or a vegetarian, or you don’t even know what you is. You understand what I’m saying? We have got to put that together first to do what? To beat Bush. That’s the key link. But the overall theme has to be to fight for a people’s democracy.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Amiri Baraka speaking in June 2004 at the first National Hip-Hop Political Convention in Newark, New Jersey. And, Felipe Luciano, that was pretty controversial, as he was pushing people to vote at that time.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Considering his former cronies, who hated electoral politics, who felt buoyed by what he had said 20 years before. Why should we invest in a white, imperialist system, institutionalized racism, not to mention personal? Why should we invest? Why should we participate in a process that doesn’t respect us? His position was, if you are here, if you call yourself American, then you have to participate. And you’re paying taxes, aren’t you? You might as well. Staying out of this system is self-destructive and self-defeating. His son—and we should add that one of the great legacies of Amiri and Amina are the progressive children.

LARRY HAMM: Right.

FELIPE LUCIANO: All of his kids, Obalaji, Amiri, all of them, are incredible. We should also add that in spite of the sacrifices that he made—his daughter was killed.

LARRY HAMM: Yes.

FELIPE LUCIANO: His sons were beaten. He was constantly threatened, not only by Imperiale at that time, but by the Mob in Newark. He was constantly—the FBI called him the father of pan-Africanism. It’s amazing that they didn’t do a COINTELPRO operation, though, Juan—and we know what happened with the Panthers with respect to that.

LARRY HAMM: Do we know that they didn’t?

FELIPE LUCIANO: We don’t know that they didn’t. But it was amazing how many leftist allies, former—or “allies” in quotes—were against him because he decided to advocate for an electoral—electoral participation in which we could defeat, with a united front, Bush. By the way, Juan had talked about this years before, before I had gotten to it.

LARRY HAMM: Could I just tell—

AMY GOODMAN: Larry Hamm.

LARRY HAMM: I read a pamphlet by Baraka in 1971, written in 1970, and I believe it was titled Toward a Pan-Africanist Party.

KOMOZI WOODARD: Oh, yeah.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Yes.

LARRY HAMM: And as early as then, in that pamphlet, Baraka talks about running black candidates for president. He actually laid out in that pamphlet the whole process that became the Gary convention process, in that pamphlet called Toward a Pan-Africanist Congress. And that’s what Gary was supposed to lead to. It was supposed to lead to the creation of a black political party. Delegates were elected to the National Convention. The National Convention elected delegates to the National Black Assembly. The National Black Assembly elected delegates to the National Black Political Council, which met in between the meetings of the Assembly. And that was supposed to be the beginning of a party. But, you know, Felipe raised COINTELPRO, and I’m waiting for other documents—I mean, I’m not personally waiting, but I think we all are waiting, as we do wait, for documents to become unclassified, so we can find out additional information.

KOMOZI WOODARD: Well, we do have the one document. We have the one document. The FBI targeted Baraka—

AMY GOODMAN: Komozi Woodard.

KOMOZI WOODARD: —because he was for unity.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Yes.

LARRY HAMM: Right.

KOMOZI WOODARD: Right? And they said he was unifying all the different ranks. And they gave the Panther formula: “Pay special attention to him. Disruption, disoriention.” Now, Baraka’s larger vision during that period of time was a Bandung West. We had been in contact with the Native American movement, the Chicano movement La Raza Unida, the August 29th Movement.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Yes.

KOMOZI WOODARD: All the different groups had said they wanted to have an anti-racist conference in 1975. If you know what happened in 1974, there was so much turbulence, we said, “OK, we’ve got too much—we’ve founded four or five different organizations in 1974. Let’s put it off ’til 1975.” COINTELPRO came at the Young Lords at that time with a vengeance.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Yes.

KOMOZI WOODARD: Young Lords was one of the most important groups in that period of time. And everything tumbled.

AMY GOODMAN: Which Juan and Felipe were a part.

KOMOZI WOODARD: So, that’s what happened. But the COINTELPRO was very active. And particularly, let’s understand how important unity is. The crime was unity.

FELIPE LUCIANO: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Let’s play some footage from the streets of Newark in 1968. This is Amiri Baraka, shot by the renowned French director, Jean-Luc Godard. It appeared in the film One P.M., or One Parallel Movie.

AMIRI BARAKA: Black art, black magic

the turn of the Earth

black art, black magic

the turn of the Earth

the Earth turns in blackness

and blackness is the perfection

of the Earth turning

blackness is the perfection

of the Earth turning

black art, black magic

the turn of the Earth

and blackness is the perfection

of the Earth turning

the perfection of the man

the perfection of God

black art, black art, black art.

AMY GOODMAN: And that is Amiri Baraka actually in the streets in 1968. For our listening audience who can’t actually see him playing, it’s Amiri himself. Sonia—oh, Juan, sorry.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yeah, no, I wanted to ask Komozi to follow up on what you were talking about. You’ve done a study of Amiri’s influence, and one of the things I think you mentioned was that there are many unpublished manuscripts that he has—he produced, that you saw at one point. Do you think there’s a lot more work yet to come out that he’s already done?

KOMOZI WOODARD: Well, yeah, when I was a kid in 1974, I went down in his basement, and he had 40 to 60 transfiles of unpublished plays, television treatments, short stories, the whole nine yards. So there’s—you have to realize that part of the consequence he paid for being political is he was censored.

LARRY HAMM: Amen.

KOMOZI WOODARD: So, there’s going to be a renaissance of Baraka’s work coming out, I would imagine, sometime soon.

AMY GOODMAN: Sonia, before we wrap up—

SONIA SANCHEZ: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: You and Amiri Baraka celebrated your 75th birthdays together.

SONIA SANCHEZ: Right, right.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about what he means, as you move on and you continue your poetry and your haikus and your political activism.

SONIA SANCHEZ: I think what I am doing, and people in my generation, what we’re doing, is that we’re remembering that there’s always something to pull onto, to hold onto. I couldn’t sleep last night, and so I went back to some of the things that I had written down that Baraka had said. And one of the things that he wrote is that—he said, “We learned that this is the function of art,” he said, because he made a comment. We are “told that Osiris, the Djali, raises the sun each day with song and verse.” He said, “We learned that this is the function of art—to give us light, to let us fly, to let us imagine and dream, but also to create, in the real world.” And that is what our dear brother did.

He said, “I—you know, I’ve got to be true to people.” He said, “I’ve got to be writing something that people can understand, but at the same time,” he said, “it’s got to be profound.” And that’s the beauty of that. He said, “I’m going to give you something. I’m going to take you a little higher, and you’re going to understand it.” It’s profound. It’s deeply deep, you know? “Come on. Listen to what I’m saying.” And that’s what we did. And he said, “You ain’t going to find it on the 6:00 news, either.” And you don’t find it on the 6:00 news.

My dear sister, I can—I can never imagine this Earth, you know, before—without Brother Baraka, without Sister Maya, Sister Toni, Sister Alice, you know, Sister Angela. I can’t imagine this Earth without Haki, because these are all the people that—you know, there are times that we argued together. I listened to the brothers there. Some of them were in the organizations. Some of them were his children. But I was a temporary—I was a contemporary. I mean, I was the same age. So we fought, you know, But what I want young people to understand, we fought. We had, you know, battles, where I said things. He said, “I don’t know what you’re doing with that old haiku. You know, you’re talking about peace all the time, you know?” So we fought.

But the next time we saw each other, we bowed and we hugged, because, you see, it’s one thing to struggle, you know; it’s another thing to love and respect and to be a part of that struggle. You know, I listen to young people talk about, “Don’t be hatin’ on me.” No, the brother wasn’t hating on me or anybody. He was struggling with ideas and philosophy. We all struggled together. And sometimes we were not on the same page. The thing that we must understand is that we loved each other. The young people must understand that we loved each other, that we knew the struggle was a concerted effort for us to change this world. Yes, we went out and said to people, “You’ve got to vote.” You know, many of us didn’t vote for a while, but at some point we understood we had to get rid of the Bush, you know, people and people like Bush. But we understood also, too, that when we elected—got elected this black president, that we still had to struggle with him and with the country, because it is the country, you know, that we are in struggle with. And that is so important.

So, yes, my dear sister and my brothers, you know, the thing about this dear brother, our brother, is that we understood his movement. He was like Du Bois. He changed. And people would say to me, “Well, you know, Baraka has changed again.” I said, “He’s like Du Bois.” I said, “When he got more information, he evolved.” You know, this is what we do. He can’t say the same thing he said from the 1960s. I’m not saying the same thing I said in the 1960s, because if I were saying that, you should say, “Something’s wrong, Sonia.” And people would have said, “Something’s wrong, Baraka.” We had to evolve. We had to change, because we traveled. We saw people. We met people. We learned. We studied. We were in the Schaumburg. We read books. We evolved, and we learned different philosophies, you know, and as a consequence, we changed. Art is change, my dear sister and brothers. And Baraka taught us that this thing called art is change.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to end with the words of Amiri himself, but I did want to ask about the use of the N-word. We’re very loath to play it on Democracy Now!, but in some of Amiri’s poetry—maybe, Komozi, if you could talk about that?

KOMOZI WOODARD: Well, I think language is very important to Baraka, and he was basically trying to make an art form out of the language that people actually speak in the streets. And so, you’ll always hear what—whatever people are saying, he would take that and then represent it in his poetry.

AMY GOODMAN: So we’re going to end with two different times in the history of this country and in Amiri’s life. This is Amiri Baraka delivering a poem about New Orleans. It’s September 2005 at a benefit for victims of Hurricane Katrina, recorded at the Bowery Poetry Club in New York City.

AMIRI BARAKA: Da dada dada da da

da dada da dada

Bye, Bye, Blackbird

Where are we?

Here, television

Stare back through us in history clothes

You know, television

Wink the blood out us

Sit ’em in a hangar

a coliseum, see ’em

Is they being lynched more hiply, huh

with water?

That’s a twist

In coliseums, Superdomes, like Rome

Kill the only Christians this land has known

TV, you’re helping too

We hip to you

That [bleep] you’re advertising

Please send it to them niggas

If they could only figure out how to grab you

and [bleep] by the throat

so y’all could no longer emote

them anti-life window dressing

for the same devil bloods

learned about on their mama’s knee

and then come out the house

can walk by theyself and find out

rich and stupid white boys is their leader

and they bleed her

They both in hoods

And one is all blood

One just got blood on their mask

Don’t ask where it come from

Look at your chest

It’s best to find out who they stabbed most recent

They is not decent

You can cry or shoot a gun

That’s the only fun left for the bereft

of all but evil titles and character assassination

They see you as if you was not beyond the proclamated

your so-called unslaveness overstated

The Superdome you starve in now your home

and dukes up the hill can rant and rave

like naked crackers in a cave

how low you is, they write

If you wasn’t so low

you’d still have a real place to live

They high with their own lie

and still got slavery’s cash

their main stash

to keep you underfoot

Does it matter what they say?

You know the story

Your pain is your own doing

It’s true

because you’re so in love with you

you won’t kill them

You’d rather hum and sing them hymns

and wonder if heaven is real as being poor

We hope it is and know it ain’t

This is hell

like that Superdome smell

like the crying child

like the darkness fell

of things gone wild

It was dangerous there even before the storm

The only clarity is the lack of charity

which the Bible says

is them that cannot love

who have it not

and nobody want it anyway

just I equal I

which is translated from political French

or self-consciousness from philosophical German

Yet the humanness of them that rule

is abstract as the food and rescue they send

They is made and rich from sin

They is yet neither women nor men

but some kind of arrogant carnivores

who pretend they is civilized

Best this is realized

before their actual teeth cut in your actual flesh

Yet it has

That mean you still don’t know

who is them so-called rulers

twelve inches of wood

with line printed on them

to measure their power

A ruler cannot, do not, will not have a soul

unless itself is human or

da dada dada da da

ba dada dada da

Bye, Bye, Blackbird.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Amiri Baraka in September 2005 at a benefit for survivors of Hurricane Katrina. And we end with Amiri Baraka in February 2009 speaking at the Sanctuary for Independent Media in Troy, New York. He read a poem called “Obama Poem,” while Rob Brown played the saxophone.

AMIRI BARAKA: Those who can’t understand what they did

and can’t understand who they are

are then lost in the moss

lost in a discourse

uncorrected, misdirected, uninspected, unprotected

never seen or known then what they, we and us

all y’all

so then be unknown to most people

except the hosts

who told them they ain’t who they is

so insist they is who they ain’t

It’s quaint

Just add a little pain

and say the same brain is the insane

and not know who you, who he, who we

blind like in Spanish cannot see sí sí

as if race was a waste

It is

Horse number three ain’t none of we

And class, was it true?

Others the same as you?

But on your head, if you’re upside down

they underground

That’s cool, it’s romantic

you get frantic

Their answer is antic

like the guy who crawl up out the bottle

and want to know if you got his bubble

but pleased to make you understand

you is another breeding space

who got their own time and place

come this far in a minute

ain’t even out of breath

come this far so soon

don’t know yourself

drunk some coon swoon

A hundred forty-five years

that’s a beginning again

Forty-four equal eight

Start in ’09, equals the time

and it’s 10, one again

come so far so quick

You come so far so quick

they forget to tell you

you wasn’t just slow

you wasn’t just uneducated

you was slick

You wasn’t just all heart

you was also very smart

How you think you was drug over here in chains

next thing we know you’re the president [bleep]

You think you could survive

amongst this hostile tribe

and not be smart plus tough

with all that heart?

Those who dug Lester Young would understand

What’s happenin’ Prez?

AMY GOODMAN: That was Amiri Baraka in February of 2009, speaking at the Sanctuary for Independent Media in Troy, New York, reading the poem called “Obama Poem” while Rob Brown played the sax.

And we want to thank our guests, who have remembered here today Amiri Baraka—Felipe Luciano, poet, activist, journalist and writer, chairman of the Young Lords; Komozi Woodard, who wrote the book, A Nation Within a Nation: Amiri Baraka and Black Power Politics; Larry Hamm, or Adhimu Chunga, chairman of the People’s Organization for Progress; and in Philadelphia, Sonia Sanchez, the renowned writer, poet, playwright and activist—as together we remember the life of Amiri Baraka. He died on January 9th, 2014, in Newark, New Jersey, where he was born. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options