Guests

- Beverly Gageprofessor of American history at Yale University who is working on a book about J. Edgar Hoover called G Man. She wrote in The New York Times Magazine about finding the letter to King during her research, in an essay headlined “What an Uncensored Letter to M.L.K. Reveals.”

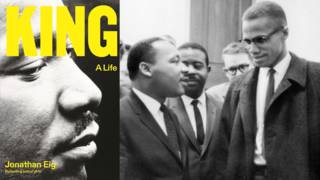

It was 50 years ago today that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover made headlines by calling Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. the “most notorious liar in the country.” Hoover made the comment in front of a group of female journalists ahead of King’s trip to Oslo where he received the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, becoming the youngest recipient of the prize. While Hoover was trying to publicly discredit King, the agency also sent King an anonymous letter threatening to expose the civil rights leader’s extramarital affairs. The unsigned, typed letter was written in the voice of a disillusioned civil rights activist, but it is believed to have been written by one of Hoover’s deputies, William Sullivan. The letter concluded by saying, “King, there is only one thing left for you to do. You know what it is. … You are done. There is but one way out for you. You better take it before your filthy, abnormal fraudulent self is bared to the nation.” The existence of the so-called “suicide letter” has been known for years, but only last week did the public see the unredacted version. We speak to Yale University professor Beverly Gage, who uncovered the unredacted letter.

Transcript

AARON MATÉ: It was 50 years ago today FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover made headlines by calling Dr. Martin Luther King, quote, “most notorious liar in the country.” Hoover made the comment in front of a group of female journalists ahead of King’s trip to Oslo, where he received the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, becoming its youngest recipient.

While J. Edgar Hoover was trying to publicly discredit King, the agency was also taking covert action. The FBI sent King an anonymous letter threatening to expose his extramarital affairs. The unsigned, typed letter was written in the voice of a disillusioned civil rights activist, but it’s believed to have been written by one of Hoover’s deputies, William Sullivan. The letter concludes by saying, quote, “King, there is only one thing left for you to do. You know what it is. … You are done. There is but one way out for you. You better take it before your filthy, abnormal fraudulent self is bared to the nation.”

One paragraph of the letter hints an audiotape accompanied the letter. It reads, quote, “No person can overcome the facts, not even a fraud like yourself. … You will find yourself and in all your dirt, filth, evil and moronic talk exposed on the record for all time.”

AMY GOODMAN: The existence of the so-called “suicide letter” has been known for years, but only last week did the public see the unredacted version. Our next guest found the full letter while researching Hoover’s personal files. Beverly Gage is a professor of American history at Yale University. She’s working on a book about J. Edgar Hoover called G Man. Her recent piece in The New York Times Magazine is headlined “What an Uncensored Letter to M.L.K. Reveals.” She’s joining us from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

Professor Gage, welcome to Democracy Now! Tell us exactly what you found and how you found it.

BEVERLY GAGE: Well, as you mentioned, I’m writing a biography of J. Edgar Hoover, and this summer I was in Washington doing some research at the National Archives. And at the National Archives, they now have a pretty full edition or copies of Hoover’s official confidential files, which were sort of the secret files that he kept in his own office. And most of them are about major public figures. These have been turned over from the FBI to the National Archives, so you have them sitting there now. And I was going through them really as part of my research for Hoover, not expecting that this letter would be there. I, of course, knew about the letter. It’s one of these really famous documents from both the civil rights movement and the history of the FBI, and so my jaw sort of dropped when I saw this unredacted version just sitting there in the National Archives.

AMY GOODMAN: So, tell us exactly what it said.

BEVERLY GAGE: It’s a very threatening letter. It has sort of two pieces to it. One are these kind of vague threats that you mentioned. “King, you’ve got to do something. You’ve got to take action. You’re a fraud. Take yourself out of public life.” And then, most of it is actually about his sex life and is about these kind of over-the-top, really racially charged, very graphic accusations about extramarital affairs, about orgies. And the implication is that all of this is on the tapes that accompanied the letter and that whoever is sending this letter has more information where all of that comes from, and they’re threatening to expose it.

AARON MATÉ: And can you talk about the context here, why the FBI, Hoover especially, was targeting King, and what surveillance tactics they employed in going after him?

BEVERLY GAGE: This letter is probably the most notorious symbol of a much wider campaign against King and against the civil rights movement, against the left in general in the 1960s. But for King, in particular, the FBI had started wiretapping several of his associates well before this letter, mostly people who were suspected of having ties to the Communist Party in the 1950s. And so, that really was the beginning of their kind of getting closer and closer to King himself. By 1963, right after the March on Washington, the Bureau had grown very alarmed about King’s growing influence, and they began to bug his hotel rooms while he was on the road, and they began to wiretap his home and his office. So, by the time Hoover held this press conference, today, 50 years ago, they had been wiretapping King. They had enormous amounts of information about King, about his personal life, about his political activities, and they had been watching many people in his circle, as well.

AARON MATÉ: Well, I want to turn to an audio recording of President John F. Kennedy talking about Dr. King. President Kennedy made these comments during a meeting about the civil rights movement on May 20th, 1963.

PRESIDENT JOHN F. KENNEDY: I think we ought to have some of these other meetings before we have it in the King group; otherwise, the meetings will look like they got me to do it. … The trouble with King is, everybody thinks he’s our boy anyway. So everything he does, everybody says we stuck him in there. So we ought to have him well surrounded. … I think we ought to have a good many others. King is so hot these days that if it looks like Marx coming to the White House, I should have the—I’d like to have at least some Southern governors or mayors or businessmen in first. And my program should have gone up to the Hill first.

AARON MATÉ: So, it’s hard to hear, so just to repeat some of the key words, Kennedy says, “The trouble with King is, everybody thinks he’s our boy … King is so hot these days, it’s like Marx coming to the White House.” When we talk about FBI surveillance of Dr. King, J. Edgar Hoover is sort of the face of it, and that’s justifiable, but he had authorization. He had authorization from President Kennedy and President Kennedy’s brother, Robert F. Kennedy, the attorney general, who signed the wiretap order. [Beverly], can you talk about how the Kennedys were involved in targeting Dr. King?

BEVERLY GAGE: Right. There was a lot of back-and-forth between the FBI and the Kennedy White House, and they were certainly sharing the fruits of what they found both before and after the wiretaps. So it’s quite clear at this point, though he denied it at certain points in his life, that Robert Kennedy did authorize the wiretaps on King and on his associates. It’s a little less clear that he knew about the bugging of the hotel rooms. But he certainly authorized the wiretaps. And the FBI was quite openly sharing a lot of this information with the White House, and the Kennedys really were responding to it. So, well before Kennedy in the middle of 1963 came out sort of fully in support of some sort of Civil Rights Act, he had been having aides and then he himself had actually pulled Martin Luther King aside, had warned him to separate himself from people in his orbit who had once been associated with the Communist Party. The FBI thought some of them were still secret members of the Communist Party or maybe even Soviet spies, and the Kennedys were very, very responsive to that sort of information. And the Kennedys were also part of a Democratic Party that was very reliant on the votes of the solid South at this point. They were very politically cautious around civil rights. And so, between these kind of secret information that’s being passed and then these political concerns, they were really very cautious about their relationship with King.

AMY GOODMAN: Moving on from Kennedy to Johnson, the journalist, New York Times reporter Tim Weiner, writes about this period, November 1964, when this letter came out, was written. In his book, Enemies: A History of the FBI, Weiner writes, “Hoover held a highly unusual press conference, calling a group of women reporters into his office and proclaiming that King was 'the most notorious liar in the country'. LBJ, conferring with [FBI Deputy Director] DeLoach two days later, expressed a degree of sympathy of Hoover’s position. [LBJ said,] 'He knows Martin Luther King,' [he went on] with a low chuckle. 'I mean, he knows him better than anybody in the country.'” Professor Gage?

BEVERLY GAGE: Well, Hoover and Lyndon Johnson were actually very good friends. They had been neighbors in the '40s. They lived on the same street. And so, they—and they were both people who loved to kind of trade in secret information. So, you have this very odd situation in which Lyndon Johnson is simultaneously kind of publicly championing the Civil Rights Act, publicly championing a lot of civil rights activism in the middle of 1964, but in these much more private conversations they're making jokes about King, particularly about his extramarital affairs, which the FBI had really started finding out about in sort of '63, ’64. This is the kind of gossip that certainly Lyndon Johnson, Deke DeLoach, who you mentioned, and Hoover himself liked to share. So you have a real disconnect both on the part of the FBI, but also on the part of the White House, between what it is that they are saying publicly during these years and what it is that they're talking about in private.

AARON MATÉ: Well, after J. Edgar Hoover called Dr. King, quote, “the most notorious liar in the country,” a reporter asked him for his response. This is a clip.

REPORTER: Dr. King, what is your reaction to the charges made by J. Edgar Hoover?

REV. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.: Well, I was quite shocked and surprised to learn of this statement from Mr. Hoover questioning my integrity. And very frankly, I don’t understand what motivated the statement.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that was Dr. King. Professor Gage, can you talk about what King did when he received this letter? It was actually after he came back from Oslo, right? Was he alarmed by it? Did they understand who it was from?

BEVERLY GAGE: So, the press conference that you were showing King’s response to was 50 years ago today, so November 18th. And right after that is when the FBI actually sent off the letter and the tape. And, however, King didn’t get it until about a month and a half later. And between that moment, there are a couple of things that happened. The first is that Hoover and King actually had sort of a public “Oh, sorry about that. Really, we’re getting along now” sort of public meeting in Hoover’s office. King went off. He received the Nobel Peace Prize. And when he came back, he found this letter and this tape waiting for him.

He knew almost immediately when he received it that it was not just some anonymous person sending him this package, but he recognized pretty quickly, as did an inner circle of his confidants, that this has come from the FBI. He understood it as a threat. There’s some evidence that, you know, he obviously was quite alarmed by this, but that it actually sank him into a certain amount of depression and alarm about what was going to come next. But he actually never spoke publicly about the letter, about the package. And it wasn’t public knowledge until the 1970s, after King had been assassinated and after Hoover had also died.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re going to end with the words of Dr. King when he was in Oslo. I was just in Oslo last weekend talking about this 50-year-ago moment. Dr. King was the youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize at this point. He comes to Oslo, and he delivers his address. And you get a sense of the horror that is going on in this country from his first words, this an excerpt from his Nobel acceptance speech December 10th, 1964.

REV. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.: I accept the Nobel Prize for Peace at a moment when 22 million Negroes of the United States are engaged in a creative battle to end the long night of racial injustice. I accept this award on behalf of a civil rights movement which is moving with determination and a majestic scorn for risk and danger to establish a reign of freedom and a rule of justice. I am mindful that only yesterday in Birmingham, Alabama, our children, crying out for brotherhood, were answered with fire hoses, snarling dogs and even death.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Martin Luther King 50 years ago, December 10th, 1964, delivering his Nobel address in Oslo, Norway. And, Beverly Gage, we want to thank you, professor of American history at Yale University, who’s working on a book about J. Edgar Hoover called G Man, wrote the piece in the Times, finding the letter to King during her research, in a piece headlined “What an Uncensored Letter to M.L.K. Reveals.”

This is Democracy Now! When we come back, the new war and old views continually being expressed on television. Stay with us.

Media Options