Guests

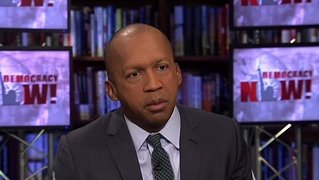

- Bryan Stevensonfounder and director of the Equal Justice Initiative. His new book is Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption.

Watch our extended interview with Bryan Stevenson, founder and director of the Equal Justice Initiative. He discusses pending executions, the history of lynching, and how Rosa Parks and others inspired him to “stand with the condemned and incarcerated.” His new book is Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. We continue with our guest, Bryan Stevenson, founder and director of the Equal Justice initiative. His new book is Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption.

I want to turn to a case right now. A Texas judge on Wednesday refused to postpone the scheduled execution of a convicted killer who suffers from mental illness and is set to face lethal injection December 3rd. Scott Panetti has had schizophrenia for decades. He won support for his case from groups like Mental Health America, psychiatrists, former judges, prosecutors and evangelical Christians. At the trial, Panetti acted as his own attorney. He wore a cowboy outfit and tried to call his witnesses, the pope, John F. Kennedy and Jesus.

Well, you write about many cases. Talk about what this case represents.

BRYAN STEVENSON: We have in our prisons about 2.3 million people, half of whom are believed to have mental illness. About 20 percent have severe mental illness. The criminal justice system, the prisons have become the repository for people with disability that have no place else to go. And that is part of the story behind this case.

The other part of the story is that we’ve created a system that is much more concerned about finality than fairness. The reason why no one’s prepared to look carefully at the clear evidence of mental illness that should block the state from carrying out this execution is that we seem like we’re in this rush, that if we don’t execute people fast, it’s almost as if it loses its potency, its value, its virtue. But my view is that if we execute people unfairly or wrongly, then we do a great deal of injustice to our whole system. And so, I think it’s tragic that we get caught up in this finality kind of focus. And you see that playing out in this case.

The Supreme Court has banned the execution of people with intellectual disability, people with mental retardation. And obviously, if you recognize that there are disabilities that can make you someone who should not be executed, you have to look more carefully at a case like this. And I think there are actually hundreds of people who have been sentenced to death when they are clearly very severely mentally ill. And a just society wouldn’t want to execute people for their disability, because that’s cruel. That’s not a decent thing to do. It’s not what a just community should do. But we’re going to do that in Texas, if we don’t take the time to think more carefully about what that case represents.

And too often, unfortunately, we don’t learn the details of these tragedies until very close to the execution time, because it’s very hard to get anyone’s attention in the death penalty space until there’s a crisis, until there’s an execution date. And that undermines the fair consideration that we often need in these cases. And sadly, it doesn’t happen at trial, because we have a criminal justice system that treats you better if you’re rich and guilty than if you’re poor and innocent. Wealth prevents many poor people and disabled people from getting their story presented in a way that might allow us to get to a just outcome. And so then we have years of appeals and litigation where maybe that story might unfold, and that’s what you’re seeing in Texas today.

AMY GOODMAN: Bryan Stevenson, have you ever tried a case in Missouri?

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yes, I represent people there, several young clients. We did a case, actually, in St. Louis of a 14-year-old kid who was accused of a murder that he didn’t commit, was sentenced to life without parole. He was tried by an all-white jury after the prosecutor excluded African Americans from serving on the jury. And we ultimately got him released after proving illegal racial discrimination in jury service.

And that’s the other backdrop. If there is no indictment in the Ferguson case, if there is no conviction, it will reveal and reflect on the way in which we select juries in this case—in this country, including in Missouri, where there’s often a great deal of exclusion of people of color, which feeds that distrust of the system. But I’ve seen that up close and personal in cases that I’ve worked on in Missouri.

AMY GOODMAN: In part one, we talked about where you grew up, but just if you could tell us again your own personal life story?

BRYAN STEVENSON: Sure, sure. Yeah, so, I grew up in a poor, rural community on the Eastern Shore in southern Delaware, that’s not unlike most Southern communities, where there was segregation. I started my education in the colored school. Black kids couldn’t go to the public schools, even though this was 10 years after Brown. And I saw my parents humiliated on a regular basis by the racial order. And one of the things—

AMY GOODMAN: What did your parents do?

BRYAN STEVENSON: My mother—my dad worked at a food factory, and my mother worked at the Air Force base up in Dover. And—

AMY GOODMAN: Where the bodies come home from war.

BRYAN STEVENSON: Where the bodies come home, yeah. And my dad did domestic work, cleaning houses down at the beach. But, you know, one of the things that bothers me the way we talk about this history is that we actually celebrate civil rights in this country with great enthusiasm, and everybody gets to celebrate—you don’t have to do anything to kind of establish some qualification to celebrate—and it’s almost as if we are kind of ignoring what’s behind the civil rights movement. We talk about the civil rights experience like it was this three-day moment, where Rosa Parks didn’t give up her seat on day one, and Dr. King led a March on Washington on day two, and then we passed all these laws. And now we celebrate—the 50th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act, the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act. And what we don’t do is talk about all the damage we did by humiliating people of color on a daily basis by subjecting people to this racial subordination, this racial hierarchy, to the distrust we created, to the injuries we imposed on people. And what I see are those injuries expressing themselves. What I see is that burden created. And because of that, I think we’re actually contributing to the legacy of racial inequality, when we just celebrate and don’t tell the truth of all of the damage that was done. I think we need truth and reconciliation in this country. In South Africa, they didn’t get past apartheid without truth and reconciliation.

AMY GOODMAN: So, I want to go to Rosa Parks.

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: And then you tell us more about what was happening then, and also what this meant to you in your own formation.

BRYAN STEVENSON: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: Rosa Parks, December 1st, 1955, one of those few moments you talk about—

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —that the whole country knows about and celebrates, is arrested when she refuses to give up her seat to a white man on a city bus in Montgomery, Alabama, the act of resistance leading to a 13-month boycott of the Montgomery bus system that would spark the civil rights movement. This is Rosa Parks in April of 1956. It’s in the midst of the bus boycott, and she was speaking on a young Pacifica Radio.

ROSA PARKS: The driver said that if I refuse to leave the seat, he would have to call the police. And I told him, “Just call the police.” He then called the officers of the law. They came and placed me under arrest, violation of the segregation law of the city and state of Alabama in transportation. I didn’t think I was violating any. I felt that I was not being treated right, and that I had a right to retain the seat that I had taken as a passenger on the bus. The time had just come when I had been pushed as far as I could stand to be pushed, I suppose. They placed me under arrest.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Rosa Parks in April of 1956. I remember, when she died and we were going down to Washington, CNN said Rosa Parks was a tired seamstress, she was no troublemaker. You were a personal friend of Rosa Parks. Was she a troublemaker?

BRYAN STEVENSON: Oh, she absolutely was. She was a proud troublemaker, because there needed to be trouble when people of color were being treated the way people of color were being treated. I mean, what people don’t know is that before that moment, she was organizing protests. There was a young African-American man who was executed for a crime that people in Montgomery absolutely insisted that he did not commit. And she was deeply affected by that wrongful execution. It was a young black man who was in a band, who was accused of an assault. They actually arrested him, took him to death row, put him in the electric chair and kept him there until he confessed to the crime.

AMY GOODMAN: In the electric chair.

BRYAN STEVENSON: In the electric chair, in the—

AMY GOODMAN: What was his name?

BRYAN STEVENSON: His name was—I’m going to forget it—[Jeremiah Reeves]. He stayed in that chair until they got that confession. And people in the black community, including Dr. King, were very concerned about organizing about his mistreatment. They could not get the relief, and he was ultimately executed for real. And it was deeply distressing to her.

And she was deeply committed to challenging the status quo. And I got to spend time with her, and she was an amazing person. She was the kind of person who would inspire people. I remember we went down to Tallahassee, Florida, where they were giving her an honorary degree, and they started playing “We Shall Overcome” at the beginning of the ceremony, and people just sat there. And she looked around at everybody, and she said, “Well, I’m used to standing when we sing this song.” She stood up, and for a moment she stood by herself, and then everybody else stood back up. And that was Ms. Parks. She was courageous. She was determined. She was very influential.

You know, I met her for the first time when she came back to be with two of her friends, Johnnie Carr, who was the architect of the Montgomery bus boycott, and a white woman named Virginia Durr, whose husband Clifford Durr represented Dr. King. And I remember being there, and I had been told, “Just sit and listen, Bryan. Don’t say a word.” And I was sitting there listening to her for two hours, and she was so encouraging. At one point she said to me, she said, “Bryan, tell me what the Equal Justice Initiative is. Tell me what you’re trying to do.” And I looked at Ms. Carr to to see if I had permission to speak, and she nodded, so I gave her my rap. I said, “We’re trying to do something about the death penalty. We’re trying to do something about mass incarceration and the treatment of the poor and people of color in jails and prisons, and children in poverty.” And I gave her my whole rap, and when I finished, she said, “Mm-mm-mm, that’s going to make you tired, tired, tired.” And Ms. Carr leaned forward, and she put her finger up, and she said, “That’s why you’ve got to be brave, brave, brave.”

Ms. Parks was a courageous woman. What defined her was her bravery, her willingness to take personal challenges, personal risks, to advance the cause of justice. And she’s really, in many ways, not fully credited for being that courageous, tenacious fighter, which I think more accurately characterized her life.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about how you went from Delaware to becoming this leading civil rights, human rights attorney, argued a number of times before the Supreme Court.

BRYAN STEVENSON: Well, you know, I got to go to high school as a result of lawyers coming into our community and opening up the public schools for me. But for their intervention, I wouldn’t be here today. And when I was in college, I was studying philosophy. I didn’t really know what to do after college and ended up going to law school by default, and was actually quite frustrated because they weren’t talking about poverty and race and justice in my first year of law school.

But then I had an opportunity to work with a human rights group that provided legal services to people on death row, and that, for me, is what changed everything. I met people literally dying for legal assistance on death row in Georgia. And I saw in them humanity and possibility and people struggling for redemption, struggling for recovery. And it was just so impactful that I knew that that’s what I wanted to do, and I went back, and I’ve been standing with the incarcerated and the condemned ever since.

And, you know, for me, it’s been a privilege, because I get to see extraordinary things. We’ve been successful in getting lots of people released, which is wonderful. We haven’t always been successful. I’ve stood next to people before they were executed, and that’s been heartbreaking and devastating. But I’ve never doubted that standing for condemned people, pushing and advocating for people who had been discarded and rejected, makes me feel more human.

AMY GOODMAN: What was it like to go into the Supreme Court for the first time?

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Not to watch it—

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —but to argue a case. And what was that case?

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yeah, well, the first case was actually the McMillian case. After we got Mr. McMillian released from death row, after he had been wrongly convicted and sentenced to death, we wanted the state to own up to it. And they weren’t. There were no—there were no statutes providing money for him. They weren’t going to pay him anything. They weren’t going to do anything. And because they had put him on death row for 15 months before the trial, because they actually hid the evidence that would have proved his innocence, we sued them. And there was a question about whether the sheriff, who had done all kinds of horrible things, including threaten him with lynching and violence, could be held accountable. And the case went to the Supreme Court on whether the county was liable for the conduct of this sheriff.

AMY GOODMAN: And this was in Monroeville, Alabama.

BRYAN STEVENSON: This was in Monroeville, yeah, out of Monroe County, whether that county had some responsibility for what it did to Mr. McMillian. And the first time I went to the Supreme Court is when I started this ritual that I’ve followed every time I stood in front of the court, and I just read where it says on the building, “Equal Justice Under Law.” And I have to believe that in order to make sense of what I do. And we went in there—I went in there and argued that case, and I’ve been back several times since. I sometimes worry that the court doesn’t fulfill that commitment. You know, we’ve done cases where the court has basically accepted evidence of racial bias and said that racial bias is inevitable in the administration of the death penalty. That’s McCleskey, a case that was decided in 1987. And so, we—

AMY GOODMAN: McCleskey, explain.

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yeah, McCleskey was a case where there was evidence presented that the death penalty in Georgia is racially biased. The researchers proved that you’re 11 times more likely to get the death penalty in the state of Georgia if the victim is white than if the victim is black, 22 times more likely to get the death penalty if the defendant is black and the victim is white. That was presented to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court accepted that evidence, but nonetheless upheld the death penalty by saying, one, if we deal with racial bias in the death penalty, it’s going to be just a matter of time before lawyers start complaining about racial bias in other parts of the criminal justice system. Justice Brennan criticized the court for its, quote, “fear of too much justice,” because in some ways the court was saying, “This problem is too big for us.”

The second thing they said was racial bias in the administration of the death penalty is inevitable. And they use that word, and it’s the reason why I think of that case as our Dred Scott of this generation, our Plessy v. Ferguson. And when I look at “Equal Justice Under the Law” and I read that decision, I realize there’s a disconnect, because you can’t have equal justice under the law while you’re pronouncing that racial bias is inevitable in something like the death penalty. And so, even though I’ve gone to the court, I still expect more from the court on these issues.

AMY GOODMAN: Dred Scott is buried just four miles down the road, on West Florissant—

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yes, yes, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —at Calvary Cemetery.

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: He went to the St. Louis court—

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —to appeal for his freedom.

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yeah, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about the significance of Dred Scott and bring it to modern-day Ferguson.

BRYAN STEVENSON: Sure. Well, that’s why I think, you know, we can run from this history of racial inequality, but we cannot hide. It’s ironic that here we are sitting here in 2014 where all of this attention is focused on Missouri—not a Deep South state, but a state where the history of racial inequality played out in very dramatic terms. Missouri—

AMY GOODMAN: People might even be surprised to know Missouri was a slave state.

BRYAN STEVENSON: Absolutely. And that’s why the story of Dred Scott, their unwillingness to give up slavery when they wanted it for economic gain, to give up this mythology of demonizing and criminalizing and abusing people of color when it created some gain for them, becomes so important, because that story in Missouri has never really been told the way it needs to be told. Missouri has the same history of racial segregation and slavery and abuse that you find in Alabama and Mississippi. We just don’t talk about it as much. Because we haven’t talked about it, we now have these presumptions of guilt following young men of color in that state, in Ferguson. And so, people in Ferguson aren’t protesting because of one thing that happened to one person. They’re protesting because all their lives they’ve been menaced and traumatized and followed and presumed guilty and dangerous. And that history has never been confronted, because we’ve never held anybody accountable for that history.

And when the Supreme Court in 1987, in a death penalty case, the case where the court says, “This is the system at its best, because we’re imposing these perfect punishments. If we don’t do it right in the death penalty context, we just can’t do it right”—and so they’re presented with this evidence of racial bias, and they’re asked to commit to eliminating racial bias, and they say, “No, racial bias is too pervasive, it’s too insidious, it’s too ever-present for us to take on. We just have to make peace with it.” And the court upholds the death penalty. And now we’ve had all of these executions in a system that is admittedly undermined by racial bias and racial injustice. And so, today, we are talking about racially biased imposition of the death penalty. We’re talking about unrest in Ferguson, Missouri. We’re talking about our failure to confront this history of racial inequality. And until we confront it and deal with it more honestly, we’re going to be having this conversation for another 50 years.

AMY GOODMAN: You’re a lawyer who argues in the Supreme Court of the United States, the highest court of the land. When Trayvon Martin was killed, the massive protests that took place on the street, right through to Ferguson, when Mike Brown is killed, what is the role of protest? What do you see it as, as a lawyer?

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: You are going into court to seek justice.

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yeah, yeah. Well, I don’t think there’s any question that without people in the street—I mean, look at the civil rights movement. We’re celebrating, you know, these legal decisions—the Voting Rights Act, the Civil Rights Act—but those acts were a response to people protesting. It was when people came back to Selma after the Bloody Sunday, after the first Selma-to-Montgomery March, which led up to the Voting Rights Act, was met with violent resistance, brutal resistance, but thousands of people came back to Selma to say, “No, we have got to do better in this country.” And it was that protest that created the political environment that made the Voting Rights Act possible. But for people out in the streets, you would not have seen the Supreme Court strike down miscegenation laws, which made it illegal in some states for black people and white people to get married, for people of different races to get married. The protests were necessary for that. And we’re going to need communities, people, ordinary people, speaking up and saying things about what is unacceptable about what’s happening in Ferguson, what’s unacceptable about what’s happening in our jails and prisons, to create the right kind of legal environment for the court to do what it must do to protect the rights of disfavored people.

AMY GOODMAN: Your group, Equal Justice Initiative, is putting out a report on lynchings.

BRYAN STEVENSON: Yeah, yeah. We are very determined to change the narrative in this country about racial history. We put out a report last year about slavery. And we actually put up slave markers and monuments in downtown Montgomery, because if you came there a year ago, you’d find 59 markers and monuments relating to the 19th century, markers and monuments to the Confederacy. We celebrate—Jefferson Davis’s birthday is a state holiday. Confederate Memorial Day is a state holiday. We name our schools after Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis. All of this stuff about the Confederacy, not a word about slavery. And so we put out a report about slavery, and we put up these monuments and markers to mark the spots where the slave trade oppressed and enslaved thousands of African Americans. And we want to keep doing that in communities across this country.

Our next report is about lynching, because we have in this country states where African Americans were terrorized. People of color in America dealt with terrorism for a generation, between Reconstruction and World War II. And they, some of them, get angry when they hear people on TV say we’re dealing with domestic terrorism for the first time after 9/11, because they grew up with terror. Lynching was horrific and terrifying. And we don’t talk about it. We put markers about the Confederacy in front of these courthouses, but we don’t say a word about the thousands of people that were lynched, hundreds of whom were lynched on courthouse lawns.

And so, we want to put out a report, and we want to actually confront communities to start dealing with that legacy, dealing with that history. It’s only when we express some shame about our racial violence, our use of violence to intimidate and menace people of color, that we commit ourselves to policing strategies, to contemporary criminal justice strategies, that make the incident in Ferguson less likely to happen. And we won’t get there until we actually create some consciousness about why it’s so important.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the role of a woman who was born a slave, a crusading journalist, Ida B. Wells?

BRYAN STEVENSON: Ah, yes. Ida B. Wells is, again, someone—you know, if there is someone who should have a national holiday, my recommendation would be Ida Wells, because she forced this country to pay attention to lawlessness. You know, I say this often. You can’t judge America by how wealthy we are, by how successful we are, by our technology. You judge a country, you judge a community, not by how you treat the rich and the powerful and the privileged, you judge a community by how you treat the poor, the incarcerated, the condemned and disfavored. And Ida B. Wells was insisting that America recognize that it is this country that is lynching people based on suspicion.

These lynchings were taking place not even because people were necessarily accused of crimes. We lynched people in America because—African Americans, because they went to the front door rather than the back door, because they laughed at the joke at the wrong time. And that racial oppression, that subordination, was something that she believed had to be exposed, if we were going to really see what kind of country we are.

And she was tormented and traumatized and terrorized herself by talking constantly about what lynching represents in American life. And eventually lynching stopped, but the mindset didn’t. And that’s why we think talking about lynching today is such a critically important issue for Americans and for this country, when it comes to racial justice.

AMY GOODMAN: What were you most surprised by as you were researching Just Mercy?

BRYAN STEVENSON: You know, I think the thing that surprised me the most is how much of what’s happened has gone unexamined. You know, most people don’t know that we have a million people in jails and prisons for drug dependency—not because they’ve committed a crime, not because they’ve hurt somebody. I think what’s really troubling to me is that we know so little. Even though we talk so much, we know so little about how we got here. You know, other countries dealt with drug dependency as a health issue. We dealt with it as a crime issue. And we’ve ruined lots of families. I don’t think most people know there are six million people on probation and parole in this country. I don’t think most people know there are—

AMY GOODMAN: And what does that mean?

BRYAN STEVENSON: It means that their lives are being controlled by the criminal justice system. It means that if they fail to make a monthly payment to the system, which they have to do, to pay their probation fee or their parole fee, they get put back in prison, sometimes for decades. It means that we are keeping them from re-engaging. They can’t get jobs oftentimes. They can’t vote. They can’t do a lot of the things that make it possible for people to have successful lives. We have 60 million people in America with criminal arrests, which means that when they apply for a job, they have to reveal that, and their chance of being hired is dramatically reduced—60 million people.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think it should be illegal to ask that question?

BRYAN STEVENSON: I think we should ban the box. I think we should do the interview, make an assessment about the person. I think there are some jobs where you can ask whether the person has been formerly incarcerated, but if you do it at the end of the interview, the chance of hiring that person is dramatically higher, because if I talk to you and I think you’re a great TV commentator and host, and I see all the skills that I want to see, and then you tell me at the end of it, “You know, by the way, when I was 20, I did something and went to jail for a short period of time,” I’m not going to let that dissuade me from hiring you, because I know you’re great. If you ask that question first, and I don’t get to see how great you are, how skilled you are, how committed you are, you’re not going to get the job. And so, that’s what we’re asking employers to do and asking companies to commit to, because what we find is that the rates of hiring for formerly incarcerated people go way up when you just do it at the end, if you do it at all.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, can you talk, Bryan, about the case you’re proudest of and tell us about that case?

BRYAN STEVENSON: You know, it’s a hard question for me. You know, Thurgood Marshall used to say—”What case are you most proud of?” He said, “The next case.” And I think it’s that way for me. I think—I take great pride in helping anybody that we’ve been able to help. But I think, for me, what I’m most proud of is that we’re still trying. I don’t think we’ve done our best cases yet. I want to believe that we’ve got important work still to do. And what energizes me is knowing that we can keep fighting, that there are challenges that haven’t been fully addressed.

You know, I’ll tell you this story. I was working on a case not too long ago, actually in the Midwest, where I was sitting in the courtroom waiting for the court to start, the hearing to start. I was sitting at defense table.

AMY GOODMAN: Where? What state?

BRYAN STEVENSON: It was actually in Iowa. And I was sitting there waiting for the hearing to begin, and I was sitting at defense table, and the judge walked in, followed by the prosecutor. And when the judge saw me sitting there, he said, “Hey, hey, hey! You get out of the courtroom. I don’t want any defendants sitting in the courtroom without their lawyers. You go back out there in the hallway and wait until your lawyer gets here.” And I stood up, and I said, “I’m sorry, Your Honor, I didn’t introduce myself. My name is Bryan Stevenson. I am the lawyer.” And the judge looked at me, and the judge started laughing. And the prosecutor started laughing. And I made myself laugh, too, because I didn’t want to disadvantage my client. And then the client came in. It was a young white kid. And we did this hearing. And afterward, I was so exhausted and frustrated.

You know, what makes me proud right now is that we’re doing this race and poverty project, because I don’t think we’re going to confront those kinds of problems. We’re going to have judges exercising judgment and discretion in this way that is so corrupted by bias and bigotry. And we’re not going to do anything about that until we start talking more broadly about this history of racial bias. And so, I’m really excited about that work.

AMY GOODMAN: Did the judge apologize?

BRYAN STEVENSON: No, no, no. He laughed. We just laughed it off, and we went through the hearing. We did well for that client, I think, because I didn’t turn that into an ugly confrontation. But no, no apologies—much like what we’ve done in this country. We don’t really—we think apologizing disempowers us. I actually think apologizing makes you more human, makes you ultimately healthier, makes you stronger. You know, I go to Germany, and I see what’s going on in that country, and you can’t go many places without confronting the legacy of the Holocaust. It makes me hopeful about the future Germany in ways that I wouldn’t be if I went there and you couldn’t see any evidence that people were talking and thinking about that history. And here we do the opposite. And I think we won’t be strong and healthy until we actually begin to reflect more soberly about what we’ve done to one another in so many of the spaces where we have racial conflict and racial inequality.

AMY GOODMAN: Bryan Stevenson, thank you so much for joining us. Bryan Stevenson is founder and director of the Equal Justice Initiative. His new book must be read. It’s called Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

Media Options