Topics

Guests

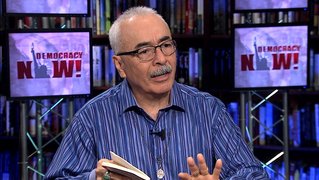

- Juan Felipe Herrerafirst Latino to be named U.S. poet laureate. He is the son of migrant farm workers and the author of 28 books, including 187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border and, mostly recently, Notes on the Assemblage. He is a past winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award and the International Latino Book Award.

United States Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera made history when he became the first Latino named to the position. A son of Mexican migrant farm workers, Herrera has been celebrated for bringing energy, humor and emotion to work that captures the consciousness of a cross-section of America. In Part 2 of our conversation, Herrera discusses his book “187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border,” the Chicano movement in the United States, and reads the poem “Almost Livin’, Almost Dyin’” from his most recent book, “Notes on the Assemblage.” The poem was dedicated to the memory of Eric Garner and Michael Brown.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. Our guest is Juan Felipe Herrera, recently became the first Latino to be named U.S. poet laureate, the son of Mexican migrant farm workers, the author of 28 books, including 187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border and, mostly recently, Notes on the Assemblage. He’s a past winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award and the International Latino Book Award. This is Part 2 of our interview with Juan Felipe.

First I wanted to go to a book you wrote years ago, 187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border. What are some of those reasons?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, they’re all there. There’s 187 of them. And—

AMY GOODMAN: And how did you come up with 187?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, you know, it’s the Proposition 187 that was in contention in California. And it blocked—you know, this was to block services for undocumented workers and peoples and communities in California, and medical services, educational services and resources. And that just didn’t—that just didn’t fit, you know? That’s not right. And so, I wanted to responded to that. You know, undocumented workers pay a lot of money into the economy, and they work under terrible wages, no insurance, and suffer abuses, including rape and other violations. So I needed to respond to it.

AMY GOODMAN: You describe yourself as Mexican, as American, as Chicano. What does Chicano mean?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Chicano means change. Actually kind of comes from the word “Mechicano,” and “Mechicano” comes from “Mechica,” and Mechica is the Nahuatl Aztec word for the Aztecs. And that is a term that in the ’60s that we wanted to make known. It used to be a pejorative term. And so we wanted to reinvent that term, because we felt we were at the tip of change, and we wanted to promote change and in a new world.

AMY GOODMAN: And can you talk about the significance of the Chicano movement in the United States?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, you know, the significance of the Chicano movement in the United States is varied. You know, there’s a lot—the first one is voices. We want our voice to be heard. We want all voices to be heard. We want our community’s voice and history and culture and experience and labor and economy to be heard, what we do here. The movement itself was to open up the educational resources in the schools, in the universities, in the communities, and to talk about labor and language and culture, and also to create binational relationships. So it was pretty thick and pretty big. And it continues.

AMY GOODMAN: In your book, 187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border, the subtitle is Undocuments 1971-2007.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: That’s right. You know, our work at times—often, very often, is not seen as valuable. It’s not in the curriculum. It’s not in the media. It’s not in the malls. It’s not present. And yet we have been here all along. So, those are undocuments. Undocumented means you don’t have an identity, you don’t have a being, you’re not a social entity, you’re just floating in space, you don’t have roots. And I wanted to bring those—bring that notion up in this book: However, we do have documents, and we do have texts, and we do have a history, and we do have a culture.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about your book called Lotería Cards and Fortune Poems: A Book of Lives.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: That’s a beautiful book, again, made through City Lights. Lotería cards, you know, lotería is quite a tradition. People have called it like a Latino or Latin American bingo game. And certain images are there that are used to count, and they’re called out. And when they’re called out—”el soldado,” “the soldier”—and then you put your penny or bean or frijole on that image, and you fill up the card. In this case, it was a collaborative project with Artemio Rodríguez, a printmaker here in the United States from Mexico, and with an introduction by Rupert García. And I had a great time responding to those images, in my poems. I made short poems. And I used words I had never used.

AMY GOODMAN: Like?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Like “disco.” And I talked about serpents, and I talked about Aztec ceremonies, and I talked about dogs crawling through the—ravenous dogs crawling through the boulevards, but all with this—you know, this internal fire and sparkling out. And there’s angels in there that are crying, and Adam and Eve. And it was just a whole different palette for me, and I just let go. I let go of my imagination in my writing.

AMY GOODMAN: And now talk about Notes on the Assemblage, even what that title means, your latest book. I mean, there it is on the cover: “Juan Felipe Herrera, United States Poet Laureate.”

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Oh, yeah, I had so much fun. At the same time, it was such a painful—such painful material. But, you know, when you write poetry, and it’s a tragic event or experience, you transform it into art. You transform it into art. And then it’s available for everyone. And when that happens, you take that very painful—you take that suffering, the very painful moment, and you give it wings, you give it honor. The art, I love the art. You know, I love assemblages in the ’60s. I love all—

AMY GOODMAN: What do you mean, “assemblages”?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Assemblage is when you put together things, and you recast them, and you give them a new form. You could put—you could put a bunch of sarapes; you could take sarapes and put them on a table and create a sculpture with them. And then, all of a sudden, those sarapes are vibrating in different manners. Those colors come at you. And maybe they look like a serpent, or maybe they look like a new being, or maybe they look like a new world. And I love doing that. And I did this with cardboard—I was inspired by William Kentridge—and drawing. I love art, visual art and experimental art and experimental writing.

AMY GOODMAN: How did you get involved with poetry? Your mom came from Mexico City, your dad from Chihuahua in Mexico, your dad a migrant farm worker. You grew up in a migrant farm-working family—

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —in California.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, you know, I love—I just happen to love language. You know, I happen to love writing. And everyone was writing, and we all—beyond writing, beyond writing, deeper than writing, we wanted to speak. We wanted to speak. I have a voice. I had a voice at that time, but I wasn’t aware of it. And when the movement for—the farm workers’ movement came along, and the civil rights movement was hot and vibrant and feverish, when students were mobilizing on the streets against Vietnam and for more rights in the schools and communities and more resources, what else can you do? You have to get up. You have to speak. You have to stand up. Whether you’re nervous or afraid, that doesn’t matter anymore. And that was my first impulse and my first mission, was to speak and to speak for our communities. And then, accompanying that, is art and writing.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you think in Spanish or English?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: I don’t know. I think in the sun and the moon and the Earth and the sky and the ocean. And that’s how—that’s what I think, how I think. And those things turn into language on paper in Spanish and in Chicano Spanish and in English.

AMY GOODMAN: And how do you dream?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: I dream—I dream in an ocean of images and memories and things I do not know and things that perhaps are about to happen.

AMY GOODMAN: In Part 1 of our conversation, you recited “Ayotzinapa”—

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: —about the 43 young me who were training as teachers in a rural teachers’ college in Mexico. And I was wondering if you could read another poem from Notes on the Assemblage.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Sure. This is called “Almost Livin’ Almost Dyin’”

for all the dead

& hear my streets

with ragged beats & the beats

are too beat to live so the graves push out with

hands that cannot touch the makers of light & the

sun flames down through the roofs & the roots that slide

to one side & the whistlin’ fires of the cops & the cops

in the shops do what they gotta do & your body’s

on the fence & your ID’s in the air & the shots

get fired & the gas in the face & the tanks

on your blood & the innocence all around & the

spillin’ & the grillin’ & the grinnin’ & the game of Race

no one wanted & the same every day so U fire &

eat the smoke thru your long bones & the short mace

& the day? This last sweet Swisher day that turns to love

& no one knows how it came or what it is or what it says

or what it was or what for or from what gate

is it open is it locked can U pull it back to your life

filled with bitter juice & demon angel eyes even though

you pray & pray mama says you gotta sing she says

you got wings but from what skies from where could

they rise what are the things the no-things called love

how can its power be fixed or grasped so the beats

keep on blowin’ keep on flyin’ & the moon tracks your bed

where you are alone or maybe dead & the truth

carves you carves you & calls you back still alive

cry cry the candles by the last four trees still soaked

in Michael Brown red and Officer Liu red and

Officer Ramos red and Eric Garner whose

last words were not words they were just breath

askin’ for breath they were just burnin’ like me like

we are all still burnin’ can you hear me

can you feel me swaggin’ tall & driving low &

talkin’ fine & hollerin’ from my corner crime & fryin’

against the wall

almost livin’ almost dyin’

almost livin’ almost dyin’

AMY GOODMAN: “Almost Livin’ Almost Dyin’” from Notes on the Assemblage, the poem dedicated to the memory Eric Garner and Michael Brown. The poet is the U.S. poet laureate, the first Latino U.S. poet laureate. His name is Juan Felipe Herrera. Talk about the time you wrote that poem, what it came out of.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, you know, I was teaching at UC Riverside, and I was living in a hotel, because my family’s in Fresno. And it just got to me. All this got to me. And I just literally just jumped out of bed in the morning, and I had to write. And I just felt perhaps it was this phrase, “Almost livin’ almost dyin’,” and I just had to put it down. And I wanted to use a lot of beats in it, literally, some mulatto rhythms, and just let the poem take me and pull me and drag me and burn me, without burning me. And then I wanted to talk and mention Michael Brown and Eric Garner, and Officer Liu and Officer Ramos, who had been killed point-blank. And I wanted to put everything together, you know? I don’t—

AMY GOODMAN: Explain who Officer Liu and Officer Ramos were.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: They were killed point-blank here in New York, and they were just in their car, probably talking, waiting and being there. And they were just shot point-blank. And so I wanted to put those four killings, four tragedies together and not apart. We have to bring it all together and feel the pain and suffering that we’re all going through with all this violence, and not just mourn for one group or not just honor one group. Let us become human beings, and let us notice that human condition that we are in right now and what we’re doing to ourselves, and let us pull back and see what we can do about it.

AMY GOODMAN: U.S. poet laureate Juan Felipe Herrera is our guest. At his inaugural reading in the Library of Congress, Juan Felipe and musician Juan Díes performed a Mexican-style ballad known as a corrido about the death of Sandra Bland, the 28-year-old African-American woman who was found dead in a Texas jail cell in July. She had been arrested by the police a few days earlier and thrown in jail. She was arrested for not properly signaling a lane change. People continue to raise questions about her death. Can you talk about what happened at the U.S. Library of Congress?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, this is a workshop, Sones de México, that Juan Díes and his ensemble presented. What happened that day when this corrido, this ballad, was written about Sandra Bland was that Juan Díes conducted a workshop on how to write a ballad, a Mexican ballad, a corrido. And he’s an expert at that. I was amazed how quickly he did it, how well he did it, and how you write the verses and the meter of each verse and how each verse has a different theme. And he asked the group to kind of have a brainstorming session and put things on the board, and Sandra Bland became the figure and the corrido hero. And everyone agreed to do that and wrote, line by line, together, which is incredible, and created this corrido.

AMY GOODMAN: Do you remember it?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Yes, I remember it.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you recite it?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: I can remember it, but I can’t recite it. I didn’t bring it with me. But, you know, it’s a beautiful corrido. You know, the thing about—there’s heroic corridos. Juan Díes mentioned this. And this corridos—most of the corridos are tragic corridos, where there’s really no rainbow at the end of the lines. And I remember—now I remember that one of the statements in that corrido mentions, “Even if you have surveillance, it’s not going to do you any good.” Even if there are cameras present recording what’s taking place, in this case in a jail cell or in a jail or in a particular environment, you may not—it just may not do you any good. And that’s in the corrido, and it’s very—it’s very sad, and it’s very true.

AMY GOODMAN: You have a remarkable bully pulpit now, the poet pulpit. What did it feel like when you heard you had been chosen? How does it work? When did you get word?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: I got word in May. And I was at University of Seattle at the American Ethnic Studies program, and Dr. James Billington called me. I thought it was Rob Casper, the director of the poetry and literature department, who leads the laureate project, and he’s been helping me quite a bit. But it was Dr. James Billington. And I started joking with Rob Casper, thinking it was Rob Casper, but it was Dr. James Billington. So he called me and said, “Would you be willing to be our 21st poet laureate of the United States?” Of course, he talked about my poetry and how he, with others, had discussed my work. And I was very honored, you know, and I was feeling like something was going to be said, and then he finally said it. And then I said, “Yes, Dr. Billington, I’m very honored and humbled.” And then he said, “Do you have any questions?” And I said, “No, Dr. Billington, not right now.” It was a big moment. It was too big for me. I had to literally find my place in that office, in the department. I had to really grab the end of the table. It’s very big, because, you’re right, it’s a national arena that I’m living in now, very palpably and very directly, with many audiences and many beautiful sponsors of many beautiful invitations.

AMY GOODMAN: You were appointed poet laureate of California by Governor Jerry Brown in 2012. In an appearance at the Library of Congress National Book Festival in 2013, you told the story of how Governor Brown quizzed you before appointing you as the poet laureate of California. Let’s go to that clip.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: He really asked me this. He says, “I want to know how I can apply 'The Waste Land' by T.S. Eliot as a governor to better serve California.” I said, “You’ve got the right feeling. You’ve got the right heart. But you’re going too far. You know? Enjoy the poem.”

AMY GOODMAN: I think Governor Brown was trying to figure out exactly what role a poet laureate plays in government. How do you see your role?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, you know, Governor Brown was great. He knows a lot about literature, and he was quizzing me, and I was—about T.S. Eliot. And it was an amazing thought. You know, we kind of had that same thought, you know, in the Chicano movement. We wanted to apply poetry into society and see if something would come about and have our communities create poetry. And it is part of society, of course. So I think that Governor Brown was getting at that, but he was really into T.S. Eliot. And I said, “You know, maybe it’s a little too much. Maybe we’re asking too much of this poem today.” But there’s a lot of good points about it.

AMY GOODMAN: Juan Felipe, why don’t we end with your choice of a poem in your latest book, Notes on the Assemblage?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: This poem is the last poem, and actually it just happened as I was finishing the book. I literally was running to the mailbox with the manuscript, and I grabbed this poem from my desk and slapped it onto the last page. It’s called “Poem by Poem,” and this is in memory of those that were killed while at church in Charleston, South Carolina.

poem by poem we can end the violence

every day after

every other day

9 killed in Charleston, South Carolina

they are not 9 they

are each one

alive

we do not know

you have a poem to offer

it is made of action—you must

search for it run

outside and give your life to it

when you find it walk it

back—blow upon it

carry it taller than the city where you live

when the blood comes down

do not ask if

it is your blood it is made of

9 drops

honor them

wash them stop them

from falling

AMY GOODMAN: Juan Felipe Herrera, United States poet laureate. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for joining us.

Media Options