Related

Guests

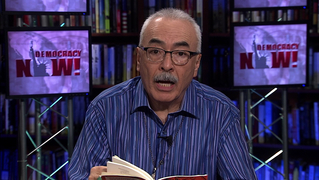

- Juan Felipe Herrerafirst Latino to be named U.S. poet laureate. He is the son of migrant farm workers and the author of 28 books, including 187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border and, mostly recently, Notes on the Assemblage. He is a past winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award and the International Latino Book Award.

We speak with Juan Felipe Herrera, who has begun his term as the 21st poet laureate of the United States. A son of Mexican migrant farmworkers, Herrera is the first Latino poet laureate of the United States. Written in both English and Spanish, his work has been celebrated over the past four decades for its energy, humor, emotion and ability to capture the consciousness of a cross-section of America. In announcing Herrera’s appointment, Library of Congress Director James H. Billington said, “I see in Herrera’s poems the work of an American original—work that takes the sublimity and largesse of 'Leaves of Grass' and expands upon it. His poems … champion voices and traditions and histories, as well as a cultural perspective, which is a vital part of our larger American identity.” Herrera is the author of 28 books, including “187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border” and, mostly recently, “Notes on the Assemblage.” He is a past winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award and the International Latino Book Award. Herrera discusses the role of poets in social movements, and reads his poem “Ayotzinapa,” about the disappearance of 43 students in Guerrero, Mexico.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We end today’s show with Juan Felipe Herrera. He recently began his term as the 21st poet laureate of the United States. A son of Mexican migrant workers, Herrera is the first Latino poet laureate of the United States. He writes in both English and Spanish. His work has been celebrated over the past four decades for its energy, humor, emotion and ability to capture the consciousness of a cross-section of America.

In announcing Juan Felipe Herrera’s appointment as poet laureate, the librarian of Congress, Director James Billington, said, quote, “I see in Herrera’s poems the work of an American original—work that takes the sublimity and largesse of 'Leaves of Grass' and expands upon it. His poems engage in a serious sense of play—in language and in image—that I feel gives them enduring power. I see how they champion voices and traditions and histories, as well as a cultural perspective, which is a vital part of our larger American identity.”

Juan Felipe Herrera is the author of 28 books, including 187 Reasons Mexicanos Can’t Cross the Border and, mostly recently, Notes on the Assemblage. He’s a past winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award and the International Latino Book Award, and joins us now in studio.

Juan Felipe Herrera, congratulations and welcome to Democracy Now!

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, thank you so much. It’s a great honor to be here, Amy.

AMY GOODMAN: What does it mean to become the poet laureate of the United States?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, you know, it means a lot. It means my whole life. It means the life of many generations of Latinos in this country and all the writing that we have done for so many years and centuries.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell me about your family, where you come from, where your parents came from.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, you know, my family—my father came from Chihuahua back in the late 1800s. He crossed the border when he was 14, probably in 1898. He was born in 1882. He was always a laborer, a farm worker, throughout his whole life, and a great storyteller and a great pioneer. My mother came from Mexico City from the barrio of Tepito, one of the poorest barrios, right after the Mexican revolution, with my grandmother and my aunt and my uncles that came before her to join the Army at Fort Bliss. And she wanted to be a dancer and a poet and a singer, but being that traditional type of world, she was kept back from doing that. So she instilled all that in me, and I always kept her spirit.

AMY GOODMAN: And where were you born?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: I was born in Fowler, California. I’m a son of farm workers, like I mentioned. And I was born in—next to Fresno, the San Joaquin Valley of California.

AMY GOODMAN: You have talked about what it’s like to live as an outlaw and brown in America.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: I have talked about that, yes. Being an outlaw, for me, means, you know, being on the margin and working with other artists and community members to bring about change, in that manner. And so, that’s what I’ve done with many people. It’s been beautiful, that part of the social changes and cultural movements of the ’60s, ’70s, to the present, and to be active to honor our communities and to work with our communities, and particularly through the word and stories and poetry and inspiration and change.

AMY GOODMAN: You’ve also said growing up in a migrant family is living in literature every day.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Yes, it is. Yes, it is, because it’s all about storytelling. It’s about telling our stories and our songs and our riddles and our sayings and proverbs. And that’s what it is. And it’s rich, very rich.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go to a clip from 1973, when you performed at the Festival de Flor y Canto de Aztlan. This is Juan Felipe Herrera’s poem, “Let Us Gather in a Flourishing Way.”

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Let us gather in a flourishing way

with sunluz grains abriendo los cantos

que cargamos cada día

en el young pasto nuestro cuerpo

para regalar y dar feliz perlas pearls

of corn flowing árboles de vida en las cuatro esquinas

let us gather in a flourishing way

contentos llenos de fuerza to vida

giving nacimientos to fragrant ríos

dulces frescos verdes turquoise strong

que sí

let us gather in a flourishing way

carne de nuestros hijos rainbows

en la luz y en la carne of our heart to toil

tranquilos in fields of blossoms

juntos to stretch los brazos

tranquilos with the rain en la mañana

temprana estrella on our forehead

cielo de calor and wisdom to meet us

where we toil siempre

in the garden of our struggle

in the garden of our joy

let us offer our hearts a saludar our águila rising

freedom

a celebrar woven brazos branches ramas

piedras nopales plumas pueblos piercing bursting

ripe mariposa fields and mares claros

of our face

to breathe todos en el camino blessing

the seeds to grow to give maiztlán amerindia

en las manos de nuestro amor

AMY GOODMAN: Juan Felipe Herrera, reading his poetry in 1973. Your hair has grown shorter, but how has your work changed over the decades?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, you know, I haven’t really left that spirit and—the bilingual spirit, and poetry for all people and our people and for poetry for our communities. Well, it’s changed because, you know, I’ve had—everything changes. And I have new experiences, and I’ve seen new things happen, and people come to me and tell me their stories. And certain things have become more pronounced through time.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about speaking in English and Spanish, writing in English and Spanish.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, it’s a beautiful thing. You know, we have many languages in this nation, and we also have fronteras, living on these things called the borders, on the border. And that’s where poetry gets reinvented and language gets reinvented. And this is part of the Chicano/Latino movement of the late '60s, post-civil rights. And it was about opening our lives and our life, how we live and how we speak and what we see and our experience and our culture. So, that's what that is, yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: On September 26, tens of thousands of people marched to mark the first anniversary of the disappearance of 43 students from the Ayotzinapa rural teachers’ college in Guerrero, Mexico, to demand answers in the case. The students disappeared after coming under attack by local police. We recently had the mothers of two of the students, Jorge Antonio Tizapa Legideño and César Manuel González Hernández, on the show. The mothers had attempted to meet with Pope Francis during his recent U.S. visit but were unsuccessful. I asked Hilda Hernández Rivera, mother of César, what support she had hoped to receive from the pope.

HILDA HERNÁNDEZ RIVERA: [translated] I know that there are a lot of people who have a lot of need and are requesting his support. But we are looking for our sons alive. We’re looking for live people. We’re not asking for any sort of material support. Imagine as a parent the sort of anguish that we feel, wondering what’s happening to our sons, whether they’ve eaten, whether they’re sick. You know your children. Well, unfortunately, we couldn’t meet with the pope, but we know that God sees all. And God knows we’re looking for our sons, and we hope that there will be a miracle and that soon we will have them home.

AMY GOODMAN: Juan Felipe Herrera, you wrote a poem about Ayotzinapa, about the missing 43 young men, and it’s in your latest book.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Yes. Yes, I did. When I heard about this news and felt it and I saw the students mobilizing in Mexico City and throughout Mexico, I was very inspired to write. And I felt. I felt so much that I had to pour it out on this—in this poem.

“Ayotzinapa”

for the students, for Mexico, for the world

From Ayotzinapa we were headed toward Iguala to say to the

mayor that we wanted funds for our rural school for teachers

it was a protest for our school that is all rural teachers nothing

more nothing less we were protesting for funds that is all we were

surrounded by police and their cronies they fired their guns they

burned us they dismembered us in trash bags they threw us into the

river yet we continue yet we march from here from the bowels of

Mexico this river that floods all the schools and all the universities

and all the floors of the emperors’ palaces we continue at twenty-

four years of age we make way through the massacre here from

where we were born and from where we died toward all the cities

in the world toward all the students and teachers in the world

demonstrating on all the streets sprung open

incandescent

no one knew it no one saw it

we are leaving this number 43 for you

because there were 43 of us

we are

not disposable

AMY GOODMAN: “Ayotzinapa.”

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: “Ayotzinapa.”

AMY GOODMAN: From Notes on the Assemblage. Explain this book.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: This book?

AMY GOODMAN: That you put together.

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, you know, I had put together another book that, after a year of writing it, it just fell apart. It just didn’t have what I really wanted in it. It was really—it wasn’t speaking. I had words on paper. This one came about because I did put together, it is an assemblage. I had written about things that were taking place that were violent, that were terrible, that happened during the last two years. And I had to write and respond to those things and the people, and hopefully send them these materials.

AMY GOODMAN: What does it mean to be poet laureate? What will you do?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: It means I have a national scope and international scope. And what I want to do is invite everybody—everybody—to speak, to say, to express themselves, whatever they want to say, whatever is deep and meaningful to them, and to enter it into Casa de Colores, House of Colors, which is on the website of the Library of Congress, so I can put out those words for everyone to see. So it’s writing, speaking, and then taking it out once again into the public’s eye.

AMY GOODMAN: Your comments on presidential candidate Donald Trump saying that all 11 million undocumented immigrants in this country should be deported?

JUAN FELIPE HERRERA: Well, you know, it’s not a good thing. It’s not a good thing to—and this is just in general, for sure. It’s not a good thing to bring about more division. You know, from my experience, from my family’s experience, from the experience of the communities that I know and visit throughout the United States, we work very hard, and we live and die in those fields. And we need support, resources, education, more educational resources, and not those kind of comments.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you so much. Juan Felipe Herrera recently became the first Latino U.S. poet laureate.

WATCH NEXT

A Conversation with First Latino U.S. Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera

Media Options