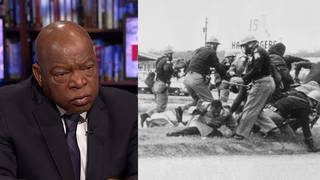

As we continue our coverage of the 50th anniversary of the historic Selma to Montgomery marches, we look at the civil rights martyrs who lost their lives in the fight to secure voting rights in Alabama. Between February and August of 1965, four civil rights activists were killed in Alabama: Jimmie Lee Jackson, Viola Liuzzo, Rev. James Reeb and Jonathan Daniels. As tens of thousands of people marked the 50th anniversary in Selma, Democracy Now! spoke to marchers who were honoring these civil rights martyrs.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: That’s the Brown Chapel AME Church Choir on Sunday. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. As we continue our coverage of the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, we turn to look at the civil rights martyrs who lost their lives in the fight to secure voting rights in Alabama. On Sunday, Attorney General Eric Holder remembered one of the martyrs, Jimmie Lee Jackson, during his speech at the Brown Chapel in Selma. Jackson was a 26-year-old church deacon who was shot dead by a police officer after a march in Marion. He was shot on February 18th; he died February 26, 1965.

ATTORNEY GENERAL ERIC HOLDER: Spurred by the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson, an unarmed young black male—an unarmed young black male—an unarmed young black male—an earlier movement began, and citizens began a march from Selma to Montgomery, across a bridge that was named for a former Alabama senator, Confederate general and grand wizard in the Ku Klux Klan. It was a march along a road that promised to be neither smooth nor straight, a road that led through difficult terrain, a road that had been traveled by generations whose footsteps still echo through history.

AMY GOODMAN: Attorney General Eric Holder inside the Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, Alabama. Well, on Sunday, more than 70,000 people marked the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday by marching across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma. During the march, I spoke with many of the people who had come from around the world. I started by asking about the civil rights martyrs.

ROD WEST: Rod West. Saw my dad get into the march. He was tear-gassed on this bridge right here. Saw my dad running back from the march, and I remember the state troopers on the horses telling people, “Get in the house,” using all kind of filthy names, “Get in the house, N—s! Get in the house, N-lovers!” or whatever. And I remember one white civil rights worker from up north picked my sister up, Rachel West, and we was trying to run into our apartment. My dad was telling us, “Get into the house.” And the state trooper actually tried to make the horse come up in the house, swinging at the civil rights workers. So my dad got tear-gassed. And I remember hearing the sirens or whatever. It was about 500 or 600 marchers. And you still had a lot of people in front of Brown Chapel Church that day, because the governor and the mayor kept sending word back to the church that they had dogs and tear gas and billy clubs, trying to scare the marchers from marching.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell me about Jonathan Daniels. We were just at Brown Chapel Church, and they raised his name. He was a white seminarian. He was an activist who came here?

ROD WEST: OK. Jonathan Daniels was a white Episcopalian minister that lived with us in the GWC Homes. And I still remember vividly that the day he was killed, he went to Lowndes County trying to register blacks to vote. They let him out of jail. It was him and a Catholic priest and two black girls. And the guy that ran the store told Jonathan that—

AMY GOODMAN: They went to buy some food at the store?

ROD WEST: Right, right. And so the guy pulled a shotgun on him and told him that he was not going to serve any blacks or N-lovers in his store. Jonathan stepped in front of the black lady, and just—

AMY GOODMAN: Because he was scared she was going to be shot.

ROD WEST: Right, right. Jonathan died instantly. And a Catholic priest, Father Morrisroe, was hit here. He’s still living today. And those two black girls are still living today. But Jonathan was killed instantly.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. King would later say that what he did, what Jonathan Daniels did, was “one of the most heroic Christian deeds of which I have heard in my entire ministry was performed by Jonathan Daniels.”

ROD WEST: That’s correct. You know, Jonathan was a brave, original man. As a matter of fact, Jonathan’s parents and girlfriend begged him to leave Selma, Alabama, and come back to New Hampshire. And I heard Jonathan tell them back in the bedroom that he was going to stay here in Selma, Alabama. He said God sent him to Selma, Alabama, to work with the poor and help people register to vote. And his mom, dad and his girlfriend just broke down and cried, because they more or less felt his death. But Jonathan said that he was not going to leave Selma, Alabama. And he didn’t.

REV. ROBERT HARDIES: My name is Rob Hardies, and I’m the pastor of All Souls Church in Washington, D.C. Our minister, James Reeb, was martyred in Selma 50 years ago this week, so we’re here today to continue his march for voting rights. James Reeb marched with Dr. King on Turnaround Tuesday, two days after Bloody Sunday. Dr. King organized another march. It was—and he marched people across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and then they turned around at the end of the bridge. Later that night, James Reeb, the minister of our church, was coming out of a black diner, and he was bludgeoned to death by three Klansmen on the streets of Selma. He died 50 years ago for the right to vote, and today we’re marching in his honor.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you tell me your name?

COREY HAWKINS: Corey Hawkins, grand master of Alabama. Jimmie Lee Jackson was a member of Goshen Lodge No. 132. He was an Army veteran who had been trying to register to vote for quite some time but was constantly being denied. At the time when he was shot, he was trying to protect his mother, who was being beaten by a state trooper. He was shot, and he was in the hospital, and he died almost a week later. But he was a member of our organization. We have film of where we carried his body four miles outside of the city limits of Marion to bury him. And we just thank God that we know that he was a member. And we couldn’t honor him any better way than what we’ve done today.

AMY GOODMAN: So we’re coming over the bridge right where the front lines were met by the Alabama state troopers, the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Can you tell me your name?

PAOLA DI FLORIO: My name is Paola di Florio.

AMY GOODMAN: And where are you from?

PAOLA DI FLORIO: And I’m from Los Angeles, California.

AMY GOODMAN: And I see you holding a sign that says?

PAOLA DI FLORIO: It says, “Be Brave, #BeBrave.” It’s a campaign that we’re running between now and August 6, when the Voting Rights Act was passed. And we’re raising awareness about what sacrifice was made to allow everybody to vote.

AMY GOODMAN: The sign says, “I am Viola.”

PAOLA DI FLORIO: That’s right.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about Home of the Brave?

PAOLA DI FLORIO: Home of the Brave is the story about Viola Liuzzo. She was a mother of five, married to Jim Liuzzo, left her family after she saw what happened here on Bloody Sunday, got up in a car, drove through three states to participate in the march, after she heard Martin Luther King call everyone to come down and help out with the march. And she did that. And she was murdered by the Klan on Highway 80. She was volunteering as a nurse. And also she gave her car to the cause, and she was shuttling people back and forth between Selma and Montgomery. And on the last day of the march, they were heading back to Selma, and she was gunned down by Klansmen and shot in the head, and she died. And the film follows her five children as they, decades later, try to put the pieces together of what happened to their mom.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell me what the back of your T-shirt says.

PAOLA DI FLORIO: “Empathy is the most revolutionary emotion.” And it’s a statement that Gloria Steinem said about Viola and about what she did here. And she’s in the film, Home of the Brave, which is being re-released. We’re re-releasing it in 50 states for the 50th anniversary of this voting rights march. And I think that that’s the key, bottom line: Viola was not a political leader, not a spiritual leader; she was a regular person like me and you.

AMY GOODMAN: Some of the marchers remembering those killed for voting rights 50 years ago.

Media Options