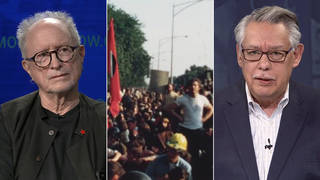

Wayne Smith served as a combat medic in Vietnam. He joined the peace movement after he returned home. He spoke recently at the recent “Vietnam: The Power of Protest” conference in Washington, D.C.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman. “Vietnam: The Power of Protest.” That was the name of a conference that was recently held in Washington, D.C., at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church. Democracy Now! co-host Juan González moderated the event.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: No one knows the horror of war more than those who fight it. And I remember when we started the Young Lords, we opened an office on 111th and Madison. And one of our first recruits—we were all in our twenties—was a 40-year-old superintendent of a building across the street, named Yaya. Yaya had been in the Korean War. He had been badly wounded, captured by the North Koreans and ended up in a POW camp. He was badly injured in his head. The North Korean doctors put a new steel plate in his head. They educated him. They treated him, he told us, differently than the other POWs because he was African-American. And he came back a changed person. And as soon as we opened up our offices in East Harlem, he was the first one to join our organization. And he taught us much about the horrors of war. We had other members who came back from Vietnam. Julio Cotto, straight out of Vietnam, the 82nd—out of Puerto Rico into the 82nd Airborne, came back a changed person. Nelson Merced came out of the Navy, destroyer, and ended up becoming the first elected Hispanic in the state Legislature of Massachusetts later on. All of these veterans returned with a completely different view of the country, their nation and imperialist war. And we’re going to hear from one veteran, Wayne Smith.

WAYNE SMITH: I’d like to start by thanking David and the entire planning committee, John and Chuck Searcy especially, for inviting me to join you and inviting other veterans to join you today. It is truly an extraordinary honor and probably one of the proudest moments of my life. But I must admit that when I saw the panel I was on, I thought, “Clearly, they must think I’m Wayne Smith, the Cuba expert, you know? The ambassador.” I mean, are you kidding me? Ron Dellums, Pat Schroeder, Tom Hayden. I truly am humbled, and I hope in some way some of what I say can make a difference.

I was just a soul brother from Providence, Rhode Island. My parents fled the paralyzing racism of Alabama and Virginia, and fled to Rhode Island, to the genteel racism in Rhode Island. There, in New England, people say, “Please screw,” you know? It’s kind of a—but my family was very strong, deeply rooted in faith and values of hard work and education, and, in fact, a belief in this country, despite the racism, that we could in fact find equality, that we could in fact achieve progress and make a difference. Unlike my parents, my brothers and sisters and I grew up in integrated neighborhoods. We went to integrated schools our whole life. It wasn’t a ghetto. Some of my best friends were Irish and Italian, Armenian, Chinese and Jewish. It was a very different world for us as opposed to our parents. But when I was 10 years old in 1961, father died. We had a house fire. In his attempts to put it out, he was burned. And that totally changed our lives. I was the eldest son of 11 children, and as a man child I felt certain responsibilities that remain with me to this day.

In our living room, we had photos of three people who were non-members of our family. It was Jesus, Dr. King and JFK. And they had the profound influence on our lives. When I was 14, I managed to bring a photo of Malcolm X into my bedroom, and my mother found it, and—but nevertheless, we were a very different family. We had different points of view and different values, and those influences always affected us.

My uncles served in the Army and Navy, and, like other African Americans before them, saw and believed that by military service, which in their minds was the most equal environment, the most equal institution that was available to African Americans—and so they encouraged military service. They saw it as something that was proud. And, in fact, I remember one discussion where my uncles were saying how African Americans serving in the military in the early days of the Vietnam even helped to support the legislative arguments for Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act. And so, it was quite traumatic, as you can imagine, when I chose to join the Army. I chose to join. I wanted to be a medic. I thought I could save lives. I thought I could make a difference. How incredibly naïve I was.

But I also had a belief that through the efforts of not only soldiers and through people that I served with—and there was in fact an incredible bond among veterans, I must say. I cannot explain it, other than what we have read about. There is the sense of brotherhood, that somehow the barriers break down. In fact, in war, even some of us, we loved one another. It was also interesting for me, as a medic, who joined—and I never wanted to kill anyone, never wanted to hurt any Vietnamese. I resisted all of the attempts by the military sergeants and trainers to dehumanize the Vietnamese. They trained us to call them “gooks” and other horrible names. Obviously, I knew immediately that, had it been a war in Africa, we’d be calling them “niggers.” So it was—we resisted, and I resisted.

But nevertheless, I participated. And throughout my 17 months in Vietnam—and I served in combat. I replaced a young man from Montana, Richard Best. He was killed two weeks shy of his 21st birthday. And when I got into combat, I was amazed with how the military truly had broken down. There were people much like me who really didn’t want to be there, who thought they were joining for one reason, and it turned out to be quite different. We did everything we could to avoid combat. As a medic, I often signed sick notes and other kinds of medical excuses, trying to help soldiers to avoid serving in combat or serving going out on operations. We talked. We shared. It was much like the bonding that I have come to learn about the antiwar movement. But we spent hours talking amongst one another about what was really happening in the world and how, if we survived, we would make a difference. And the world was a place. We wanted to get home. We just wanted to survive. And yet, there is an enormous guilt, that stays with me and many of my brothers and sisters today, that we should have known better. We should have been sitting where you are, that we should have been more active, more informed and more in opposition to that war. But that wasn’t the case.

Having come home, having survived from the war, I’ve tried to keep a commitment that I made. In part, it was to God, that if I was able to survive, if I was able to save lives, if I was able to make a difference—and the one small shred that—that even today gives me chills, was I had the chance to assist, in a very remote way, with the bringing of a Vietnamese child’s life into the world. Midwives were working, and I assisted. And it was truly like a redemptive, almost baptismal moment. So, I have overcome some of those—those horrors of war, like so many veterans—my dear friend Bobby Muller, Michael Leaveck, David Addlestone, David Evans, all of us, Gary May—the list goes on—to those of us who didn’t want to be in war. And when we came home, we kept the commitment to serve in peace movement, to work for human rights and social justice. We were amongst the group of veterans who led the effort to help Senator Kerry and McCain normalize relations with Vietnam. Indeed. Our dear friend Bobby Muller created the Vietnam Veterans of America Foundation. We created prosthetic clinics in Cambodia and Vietnam, Angola and numerous other countries, and participated in efforts to ban landmines. So we have—thank you, yes. The work goes on, that we stand in solidarity with you. It is truly an honor for me to, in a small way, represent those veterans of conscience, like yourself, working for peace. Thank you very much.

Media Options