Guests

- David Goodmanbrother of Andrew Goodman. On Sunday, he wrote an editorial for Mississippi’s Clarion-Ledger newspaper headlined “U.S. Has Turned Pages, Not Closed Book on Racism.” He is president of the Andrew Goodman Foundation.

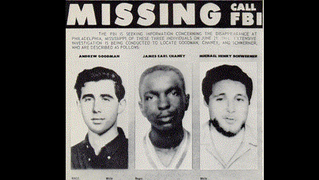

Sunday marked the 51st anniversary of another hateful act tied to another historic black church. It was June 21, 1964, when three young civil rights workers were murdered in Philadelphia in Neshoba County, Mississippi. Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner went missing after they visited an African-American church which the Ku Klux Klan had bombed because it was going to be used as a Freedom School. We speak to David Goodman, brother of Andrew Goodman. On Sunday, the 51st anniversary of Andrew’s death, he wrote an editorial for Mississippi’s Clarion-Ledger newspaper headlined “U.S. Has Turned Pages, Not Closed Book on Racism.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Reverend Barber, you mentioned Philadelphia, Mississippi. This past Sunday marked the 51st anniversary of another hateful act tied to another historic black church. It was June 21st, 1964, when three young civil rights workers were murdered after they left a burned black church in Longdale, Mississippi. Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, Michael Schwerner went missing after they visited the church in Neshoba County, Mississippi, which the Ku Klux Klan had bombed because it was going to be used as a Freedom School. This clip is from the documentary Neshoba: The Price of Freedom, picking up the story. We hear from retired FBI agent Jim Ingram, reporter Jerry Mitchell. It begins with former U.S. Assistant Attorney General John Doar.

JOHN DOAR: Three civil rights workers were missing, and they had last been seen going up to investigate a church burning in Neshoba County.

NEWS ANCHOR: It’s 35 miles from Meridian to Philadelphia, then 12 miles to Longdale, where the church had been burned. That afternoon, the three were seen at the church site and at the home of its lay leader. About 2:30 they headed west toward Philadelphia.

JIM INGRAM: Chaney was outside changing the tire. They had a flat. And there was Price. And when they pulled up, he said, “I’m arresting Chaney for speeding; Schwerner and Goodman, for investigation.”

JOHN DOAR: Cecil Price, deputy sheriff, saw them and stopped them, and he takes them into the jail. So, somehow, some way, the message gets out to the Klan, and then they have to organize.

JERRY MITCHELL: Edgar Ray Killen began to kind of coordinate things that night, kind of gathered a group of guys, had one of them go get gloves so they wouldn’t have fingerprints, told them the guys they wanted were there in the jail.

NEWS ANCHOR: By 10:00, Price says he had located a justice of the peace who fined the trio $20. Price tells what happened then.

DEPUTY CECIL PRICE: They paid the fine, and I released them. That’s the last time we saw any of them.

JOHN DOAR: The boys were driving back from the county jail, and they started down the road toward Meridian, and they were stopped by a police car. And there would be this group of Klan people.

JERRY MITCHELL: They arrested them and put them in Price’s car.

JOHN DOAR: Then turned right into a gravel, rural road.

JERRY MITCHELL: And Alton Wayne Roberts grabbed Schwerner, and he said to him, “Are you that 'N-word' lover?” And Schwerner said, “Sir, I understand how you feel.” And, bam, shot him, grabbed Goodman. Goodman didn’t even get a word out. Shot Goodman. Chaney, by this point, obviously realizing what’s going down, took off. We know he was shot by several people. They also apparently beat him.

AMY GOODMAN: And that was Jerry Mitchell, who is with the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, describing what happened to Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Mickey Schwerner, an excerpt from the film Neshoba: The Price of Freedom.

We’re joined in our New York studio by David Goodman, Andrew Goodman’s brother. On Sunday, the anniversary of Andrew’s death, he wrote an editorial for Mississippi’s Clarion-Ledger newspaper headlined “U.S. Has Turned Pages, Not Closed Book on Racism.”

Welcome to Democracy Now!, David. Again, this anniversary took place on Father’s Day. And you commented, the first Father’s Day your dad was alive to learn of his—would soon learn of his son’s death.

DAVID GOODMAN: Yes, it’s ironic, in a way. You know, these stories, you couldn’t write them in fiction. But June 21st, 1964, was Father’s Day. And my brother and James Chaney and Mickey Schwerner were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan that evening. And 44 days later, we found out definitively, because the bodies were found, by informants, buried 15 feet under the ground in a dam that was under construction.

AMY GOODMAN: And your thoughts today, in the midst of the horror then? It’s 51 years later, as you listen to this discussion, and yet another massacre has taken place, this time in South Carolina. You were just in Selma for the anniversary of the Selma marches.

DAVID GOODMAN: Yes, well, you know, I sort of came of age. I was 17 years old when this happened. And it’s not like all of a sudden I’m finding out about these issues. You know, my grandfather used to say, “Ask a 17-year-old a question; they know everything.” I thought I knew everything, like all other 17-year-olds, but I was shocked to learn that the self-evident truth that all people are created equal wasn’t necessarily true, and there’s a big gap between the ideals and the practices. And it’s been 51 years to march through, for me, personally, this realization about the complexity of our great nation. And it is a great nation, to me, but we have profound flaws.

The conversation about the flag is a symptom or a symbol of what has and remains wrong, but it’s not underlying the fundamental issues. Reverend Barber has identified those fundamental issues. When you have an educational system that, for example, leaves out a big part of the population, frequently minorities, there’s no hope that they can move up the economic ladder. When they don’t get healthcare, they’re not going to be healthy and can’t participate in the democratic process. So all of these things are related.

The flag that we’re talking about so much is a symptom. I believe it needs to be removed. I mean, from the time we’re children, we see the American flag on one side or the other of the chalkboard, and we put our hand on our hearts, and we repeat these unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, but some people who do that aren’t recipients of those great benefits. And we have to, however—however, when our flag and those principles are challenged, like ISIS chopping off heads of our citizens, it’s a tremendous outrage to our people, understandably, but on the other hand, we have—and those are foreign terrorists—we have a white-born person who not over a period of a year kills four Americans, but in two minutes kills nine—so, in domestic terrorism. So, these are the challenges we’re facing.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to turn to Doug Brannon, where we began this conversation, the South Carolina state representative in Spartanburg who’s introducing the bill to bring down the flag. Right now, police have confirmed that the Charleston church shooter, Dylann Roof, and Michael Slager, the former police officer who shot Walter Scott in the back, are neighbors in jail cells in the Charleston jail. But I want to end by asking you about what you would like to see the legacy of Clem Pinckney be, the state senator. We know about—we’ve heard about the legacy and heritage of the Confederate flag and the violence around that. How do you want your friend, your fellow legislator, the Reverend and State Senator Clementa Pinckney, to be remembered? With what kind of legislation will you be participating?

REP. DOUG BRANNON: Well, I will be participating in the legislation to remove the flag. But your question is: What is Senator Pinckney’s legacy, or what would I like it to be? And the answer to that question is not what I would like it to be, it’s what it absolutely is. On Friday afternoon, I saw the most incredible thing that I’ve ever seen in my life. I saw the family members of nine deceased heroes face a shooter and talk to him with love, forgiveness and salvation. Those people learned that from the great teacher, Clementa Pinckney. His legacy is the lessons that he taught and the life that he lived.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you very much for being with us, taking this time, from Spartanburg. You’re headed to Columbia, where this discussion, this debate, is going to take place. Republican South Carolina State Representatives Doug Brannon and Gary Clary, speaking to us from Columbia, Reverend Dr. William Barber, speaking to us from Raleigh, North Carolina, historian Don Doyle from Columbia, and David Goodman, joining us here in New York, brother of Andrew Goodman.

Media Options