Related

Guests

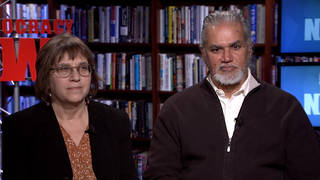

- Liz Garbusdirector of What Happened, Miss Simone? which opens today in theaters in New York and Los Angeles, and releases on Netflix on Friday. Her 1998 documentary, The Farm: Angola, USA was nominated for an Academy Award.

- Al SchackmanNina Simone’s guitarist and music director for over 40 years.

As the Black Lives Matter movement grows across the country and the the nation mourns the death of the nine worshipers killed at Charleston’s Emanuel AME Church, we look back at the life of one of the most important voices of the civil rights movement: the singer Nina Simone, known as the High Priestess of Soul. While Simone died in 2003, a new documentary, “What Happened, Miss Simone?,” sheds light on her music and politics. Her song “Mississippi Goddam” became an anthem of the civil rights movement. She wrote it in the wake of the assassination of Medgar Evers in Mississippi and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, which killed four black children. We speak to the film’s director, Liz Garbus, and Al Schackman, Nina Simone’s guitarist and music director for over 40 years.

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: “Alabama’s gotten me so upset, Tennessee has made me lose my rest, and everybody knows about Mississippi Goddam.” Those were the words the legendary singer Nina Simone wrote five decades ago in the wake of the assassination of Medgar Evers in Mississippi and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, killing four black children. “Mississippi Goddam” would become an anthem of the civil rights movement.

NINA SIMONE: [singing] Hound dogs on my trail

Schoolchildren sitting in jail

Black cat cross my path

I think every day’s gonna be my last

Lord have mercy on this land of mine

We all gonna get it in due time

I don’t belong here

I don’t belong there

I’ve even stopped believing in prayer

Don’t tell me

I’ll tell you

Me and my people just about due

I’ve been there so I know

They keep on saying “Go slow!”

AMY GOODMAN: Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam.” Well, 50 years later, Nina Simone’s message remains as relevant as ever, as the Black Lives Matter movement grows across the country and the nation mourns the deaths of the nine worshipers killed last week at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston.

While Nina Simone died in 2003, a new documentary sheds light on the music and politics of the singer known as the “High Priestess of Soul.” The documentary, What Happened, Miss Simone?, opens today in theaters in New York and Los Angeles, and releases on Netflix on Friday. This is the film’s trailer.

NINA SIMONE: I think the only way to tell who I am these days is to sing a song. We’ll start from the beginning.

LISA SIMONE KELLY: My mother was one of the greatest entertainers of all time. When she was performing, she was an anomaly, she was brilliant, she was loved.

COMPÈRE: The one and only Nina Simone!

GEORGE WEIN: Her voice was totally different from anybody else. Let me listen to it again. How is she doing this?

STANLEY CROUCH: She was one of those musicians, you hear them once; the next time you hear them, you say, “Oh, that’s that same one I heard last week.”

LISA SIMONE KELLY: People think that when she went out on stage, she became Nina Simone. My mother was Nina Simone 24/7. And that’s where it became a problem. Everything fell apart. She was a revolutionary. She found a purpose for the stage.

NINA SIMONE: I choose to reflect the times and the situations in which I find myself. How can you be an artist and not reflect the times?

AL SCHACKMAN: There was something eating at her.

LISA SIMONE KELLY: When the show ended, she was alone, full of anger and rage.

NINA SIMONE: I have to live with Nina, and that is so difficult.

AL SCHACKMAN: Nina was fighting demons. She could get violent.

NINA SIMONE: Hey, girl. Sit down.

AL SCHACKMAN: The change in her would be dramatic—mm, like a switch.

NINA SIMONE: Sit down!

LISA SIMONE KELLY: As fragile as she was strong, as vulnerable as she was dynamic. Most people are afraid to be as honest as she lived.

NINA SIMONE: I had a couple of times on stage when I really felt free.

COMPÈRE: The High Priestess of Soul.

UNIDENTIFIED: Miss Nina Simone.

COMPÈRE: Nina Simone!

ANNOUNCER: Nina Simone.

LISA SIMONE KELLY: She was a genius. She was brilliant. But she paid a huge price.

AMY GOODMAN: The trailer for the new documentary, What Happened, Miss Simone?

To talk more about Nina Simone’s life and work, we’re joined now by two guests. From Martha’s Vineyard Community Television in Massachusetts, Al Schackman joins us. He was Nina Simone’s guitarist and music director for over 40 years. And here in our New York studio, we’re joined by filmmaker Liz Garbus. Her 1998 film, The Farm: Angola, USA, was nominated for an Academy Award. Her new film, What Happened, Miss Simone?, opens today in theaters in New York and Los Angeles, releases on Netflix on Friday.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! This is an epic film that comes at such a critical time. First, start with the title, Liz, What Happened, Miss Simone?

LIZ GARBUS: What Happened, Miss Simone? derives from an article that Maya Angelou wrote in 1970 for Redbook. Nina had been—you know, was the patron saint of the rebellion, and she was a leader in the movement. And then, after the murders of so many of her colleagues and compatriots and fellow travelers, she had had enough. She had had enough with America, and she left. And the article, and the question in the article, “What happened, Miss Simone?” was asking, you know, where is she? Where are these voices? What happened to Nina? And so the film kind of uses that as a frame to unravel, you know, how we understand Nina Simone’s career, her art, her commitments.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And why did you decide to make this film? And can you talk especially about some of the archival footage that you were able to put together in it?

LIZ GARBUS: You know, in my view, Nina Simone is one—you know, was one of the greatest artists of the 20th century, right up there with Miles Davis, James Brown, Bob Dylan, and, possibly because of race and gender, was not—and the combination of the two, in her case, you know, had not been regarded that way, and especially here in the U.S., where I think she had been overlooked and forgotten and certainly misunderstood, as her song intimates. And so, we were able to, with the permission of the estate, get—do a really, really deep dive into Nina Simone, not just the concerts and the performances, which of course make up the heart of the film, but also private tapes of Nina talking about her life, you know, 30, 40 hours of that, diaries, letters, notes, and interviews with some of her most intimate friends and family members.

AMY GOODMAN: Give us a thumbnail biography of Nina Simone, if you can. I mean, her life spans years, both in the public eye and outside of the public eye.

LIZ GARBUS: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: But she wasn’t born Nina Simone.

LIZ GARBUS: No, she was born Eunice Waymon in Tryon, North Carolina, the daughter of two very religious parents. Her mother was a minister in a church. And from a very young age, people noticed in church that Nina was incredibly talented at the piano. When she was about six years old, some white folks in that community thought, “Oh, maybe we have a prodigy on our hands here,” and they took up a collection to get Nina—Eunice Waymon, get her a classical music education. So, from that age, she started crossing the railroad tracks to the home of Ms. Massinovitch, who, again—who gave her—you know, schooled her in Bach and the classics. Nina was extraordinarily talented. They raised money, enough to get her to Juilliard here in New York. And her dream was to become the first black classical pianist in Carnegie Hall. After one year at Juilliard, she applied to the Curtis Institute, and then the money—and she did not get in. And the money ran out.

This was when Eunice Waymon became Nina Simone. She started—her parents, her family, had moved up north to be around her. She started playing in bars and clubs, and singing what her family considered to be the devil’s music. So she changed her name to Nina Simone so it would go underneath her mother’s radar. One night in a bar, they said to her, “You know, if you want to make some money, you better sing.” And that’s when Nina Simone began singing. So this was never the intended path for her career. Throughout her life—you know, she lived to age 70—she lamented that she didn’t get to explore that classical path to its fullest. But, of course, she also found great joy and triumph in her involvement with the civil rights movement, which of course then also led to her deepest disappointments.

AMY GOODMAN: And before that, why she didn’t pursue the classical music, she went to Juilliard, but then tried to get into Curtis music—school of music in Philadelphia.

LIZ GARBUS: That’s right. And she did not gain acceptance. And that was one of the finest schools, and it would be paid for. And once that was taken away from her, she couldn’t continue that education.

AMY GOODMAN: And why was it taken away?

LIZ GARBUS: Her view was that she—it was because of race. And Curtis Institute denied that. But, of course, there were very, very few black students who had ever been accepted to Curtis. You know, it was—it was the ’50s, you know, so, certainly, we imagine that it played a role.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we want to get to the civil rights years, and also, in addition to speaking to Liz Garbus, the Academy Award-nominated filmmaker, we want to speak with Al Schackman, who was Nina Simone’s guitarist and music director for over 40 years. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Nina Simone singing “Sinner Man.” This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González. Our guests are the Academy Award-nominated filmmaker Liz Garbus, director of a number of films, but most recently, What Happened, Miss Simone?, opening today in theaters in New York and Los Angeles and on Netflix on Friday; and we’re joined by Al Schackman, Nina Simone’s guitarist and music director for over 40 years. He’s joining us from Martha’s Vineyard. Juan?

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, Al Schackman, I’d like to bring you into the conversation. Talk to us about how you first met Nina Simone and how you developed your collaboration that lasted over so many decades.

AL SCHACKMAN: Good morning. I met Nina in 1957 in the art community, village of New Hope, Pennsylvania. I was playing there with my trio in a restaurant, and Nina was playing at the Bucks County Playhouse Inn. And some friends of hers had visited with her from Philadelphia and were having dinner and heard me play and thought it might be a good idea for the two of us to get together. And they asked her, and she agreed. And on a night off, I went down with my guitar and amp, and set up. And she was on a break. And I just was ready to play with her, and she came on stage and never looked at me or told me what she was going to play. And we both had perfect pitch. And she started the introduction to her song “Little Girl Blue,” which was a Bach piece, and it was a fugue. And I came in with a third part. And she started singing “Little Girl Blue,” and then she looked up at me, and we were off and running from there.

AMY GOODMAN: Forty years.

AL SCHACKMAN: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: I want you to tell us the story of her meeting Dr. King, but, Liz Garbus, give us the civil rights years, because it started before that meeting—

LIZ GARBUS: Absolutely.

AMY GOODMAN: —Nina Simone’s relationship with what was going on in this country.

LIZ GARBUS: Yeah, Nina was pursuing a career that was—you know, after “I Loves You, Porgy” was a smash hit, she was pursuing a career and, you know, sort of filling a role that people handed to her, which was of the jazz singer. Now, this was not what Nina Simone wanted to be. This was not how she saw herself. In 1963, after the church bombing, Nina—

AMY GOODMAN: In Birmingham.

LIZ GARBUS: In Birmingham—Nina changed course. She wrote “Mississippi Goddam.” And, you know, her career would never be the same from then on. She talked about, you know, when she was growing up, nobody talked about race. But, of course, her entire being was infused, growing up in the Jim Crow South and existing in America, a segregated, racist America. And she changed course in her career, and she said, you know, right now her mission and her passion was to make music that would help her people. And so she continued to make some of the great anthems of the civil rights movement—”Young, Gifted and Black,” “Backlash Blues,” “Old Jim Crow.” You know, she continued, of course, “Mississippi Goddam.” And she collaborated with the great intellectuals of the day. Lorraine Hansberry wrote “Young, Gifted and Black” for her. Langston Hughes wrote “Backlash Blues.” She hung out with James Baldwin, Miriam Makeba, Stokely Carmichael, ultimately lived next door to the Shabazz, Malcolm X family. So she was part of the circle of activist black intellectuals, and she had quite a political awakening. She and Al went to the Selma march together. And he, of course, can talk about that, yeah.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Al, you aren’t exactly a stranger to, one, the civil rights movement or, two, the great artists of the time. You also played with Harry Belafonte, as well. Can you talk about how you juggled that and how—and your involvement in the civil rights movement?

AL SCHACKMAN: Yes. Nina was not performing regularly, and I had the opportunity to go on with Harry Belafonte on fundraising tours with Martin Luther King. And we would fly to different cities, and we actually were in Europe with him, as well. And it was a great opportunity to be able to get next to Martin and really feel the spirit of where he was coming from. And that is what America came to see, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: And tell us about Nina and Martin Luther King meeting for the first time. Where were you all, and what happened?

AL SCHACKMAN: Well, we were at a fundraiser, and we approached Martin, and he put his hand out. And before anything else could happen, she just, in a very strong voice, looked at him and said, “I’m not nonviolent.” And he said, “Oh, that’s OK, Sister. You don’t have to be.” And he put his hand out, and they shook hands. And it was a very warm meeting after that.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And the events of Selma?

AL SCHACKMAN: We were playing at The Village Gate in New York, and we flew down with Nina’s husband, Andy Stroud, and were going to land in Montgomery. And we couldn’t land, and we flew over the runway, and it was filled with trash trucks, garbage trucks, all kinds of equipment. And the governor of Alabama had had that put out so that we couldn’t land. We eventually landed in Jackson, Mississippi, and chartered a single-engine, little single-engine plane. And we were kind of heavy, and the nose gear went up in the air like that, and the pilot said, “Well, we can’t take off like that.” And we switched seats. Andy was moved up forward with my amplifier, and the plane settled down.

And we took off and landed on a small runway in Montgomery and had to go through Alabama National Guard to get to the stage at the soccer field of the seminary. And there was a—it was a big platform. The stage had a little scrim around it, a little curtain. And I lifted up the curtain to see if I could plug my amp in somewhere, and saw that the stage was built on coffins, that were supplied by the black mortuaries in Montgomery. And it was pretty chilling to see that.

AMY GOODMAN: Nina Simone was deeply affected by Dr. King’s death.

LIZ GARBUS: Nina, yeah, she was. She was. And again, you know, she espoused probably a slightly different political doctrine than he, yet—and then, when you listen to her song, “The King of Love is Dead,” you can see how much—how much it broke her. You know, her colleague Stokely Carmichael said, when black—when white America killed Dr. King, they killed the best chance for peace and for healing. And, you know, certainly, after the massacre in Charleston and what’s been—you know, we see that perhaps that was true.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And then, in the ’70s, she goes into self-imposed exile, goes to Africa and Europe. Could you talk about that period of time in her life?

LIZ GARBUS: Yeah, they’re her nomadic years. I mean, she definitely—after leaving the States, she led more of a nomadic life. She goes to the Caribbean for a while, then to Liberia, where she said, you know, “This was a country formed by freed slaves, and this is where I should be.” But no money came in. She couldn’t—she didn’t want to sing. She wanted to be out of the business for a while. But she also then realized she had to eat, and she went back to Switzerland.

And in Switzerland, she goes to the Montreux Jazz Festival and gives quite an infamous performance, where she’s clearly in a great deal of turmoil, doesn’t want to be in a jazz festival, but must be there. The piano draws her. She loves the piano, but also it became quite a burden for her, as well. She ultimately settles in France and in Holland, you know, amongst friends, and seeks—ultimately, with the help of her friend Al and other friends, gets mental health treatment, because she was, as we see in her diaries and as her friends reported, suffering from, you know, pretty severe depression.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to play a few clips from this astounding film. Let’s go to What Happened, Miss Simone?

NINA SIMONE: I really need to provoke this feeling of like, who am I, where did I come from? You know, do I really like me? And why do I like me? And like, you know, if I am black and beautiful—I really am, and I know it, and I don’t care who cares or says what.

[singing “Ain’t Got No (I Got Life)”]

AMY GOODMAN: Nina Simone singing. And let’s go to another clip of What Happened, Miss Simone?

NINA SIMONE: This song was popular all over France. It’s from my first album, the very first album we made in this world, which is at least 25 years old. I only wish I was as wise—could have been as wise then as I have become now. I have suffered. But there’s a Bösendorfer here, so we’ll see what happens. “My Baby Just Cares for Me.”

AMY GOODMAN: And in this clip from the film, What Happened, Miss Simone?, we hear from Nina Simone’s daughter, who lives in Paris, France, now and is a performer. Her name is Lisa Simone.

LISA SIMONE KELLY: My mother was one of the greatest entertainers of all time, hands down. But she paid a huge price. People seem to think that when she went out on stage, that was when she became Nina Simone. My mother was Nina Simone 24/7. And that’s where it became a problem.

NINA SIMONE: [singing] One day I thought I could fly

one day I woke up and I could fly

I’d look down at the sea

and I wouldn’t know myself

I’d have new hands

I’d have new feet

I’d have new vision.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Nina Simone singing, as well as her daughter, Lisa Simone Kelly, who’s performing in Paris, France, now. But, Liz Garbus, where does she live?

LIZ GARBUS: She is now living in her mother’s home, the home that her mother passed away in, in the south of France, Bouc-Bel-Air. So—and after a career in the military. Lisa Simone Kelly was in the Air Force for 11 years, kind of doing—getting as far away, I think, from her parents as possible, given Nina’s feelings about the U.S. government. But now she’s kind of gone full circle and is pursuing a career of music herself.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And you also look in the film not only at—obviously, at her work, in her civil rights work and her music, but also her personal life and the trials she went through, the very abusive relationship she had with her longtime husband. Could you talk about that, as well?

LIZ GARBUS: Yeah, sure. And, of course, Al was witness to a lot of the violence in the home. She married a former police officer—she married a man who was a police officer, who then retired from the police force to manage Nina Simone. The husband-manager thing has never really worked out too well for artists over time; I think it’s something that we can settle. But yeah, indeed, for them, it was quite fraught with both violence, pressure, you know, different goals. When Nina became involved in the civil rights movement, the commercial side of her career suffered. That became an issue between them, another antagonist between them in their marriage. But their marriage was—you know, it was complicated. As Lisa, Nina’s daughter, said, it was a little bit like inviting the bull with a red cape into your kitchen—you know, let’s see what you can do. Nina wrote in her diaries, “I love physical violence.” There was part of her that clearly engaged in this with her husband. So it was quite a complex relationship that we didn’t want to oversimplify, because we do see Nina’s perspective on it.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Al Schackman, you lived it up close. You were with Nina Simone for over 40 years. If you could describe—well, you have the deterioration of Nina’s mental health, but also her wanting to sing these songs in the civil rights movement and what it meant commercially. I mean, you were with her. You were her guitarist. You were her music director.

AL SCHACKMAN: Well, her songs were threatening at the time, and the popular powers that be in the music industry were afraid to bring her on to any projects or record deals after a while. But the political undertones were always there. In “Mississippi Goddam,” I mean, even today, the black community in this country doesn’t necessarily want you to be their next-door neighbor. But as the song says in “Mississippi Goddam,” you don’t have to live next to me, just give us our equality. And Nina was very strong about that. She—that and women’s rights, as well. She was really a pioneer, and her political views really forced her out of the United States at the time.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Al Schackman, your fondest memories of your time with Nina Simone, when you were out of the public limelight, when you were just the two of you together, what do you recall?

AL SCHACKMAN: Very gentle, very quiet. We kind of had a telepathic communication, as we did in the music. And she was fun-loving and very gentle. Our best times were alone. And actually, our best times musically were when it was just she and I, and we had nothing in the way of this pure musical interaction. But one time when we were alone in Holland, she said, “Let’s go for a drive.” And I said, “Where?” She said, “I’ll show you.” We drove miles out into the countryside, and now we’re on a dirt road. And she says, “Turn right.” And we see some Quonset huts, and we come up to the Quonset huts, and it was an airfield. And I said, “What are we doing, Nina?” And it was a glider field. And she said, “We’re going up.” And she knew everybody there, and she loved to go up in gliders and do sail planing. And up we went. And we’re circling around, and she’s below me in another glider, and she waves up with a big smile, and I wave back at her, and she was at peace. It was really amazing.

AMY GOODMAN: And in the last 15 seconds, what you hope to do with this film, Liz?

LIZ GARBUS: Well, I think Nina is a model of how an entertainer inspires and engages politically. And I think today she’s a voice we need sorely. And I think that, you know, for other artists and celebrities today kind of looking to get involved in the movement, Nina Simone did it, and she inspired people, and she never compromised.

AMY GOODMAN: Liz Garbus and Al Schackman, we thank you both for being with us. Liz Garbus, the Academy Award-nominated filmmaker. This new film, What Happened, Miss Simone?, opening today in theaters in New York and Los Angeles, releases on Netflix on Friday. And Al Schackman, up in Martha’s Vineyard, guitarist and music director for over 40 years. Thanks so much to Martha’s Vineyard Community Television.

Media Options