Topics

Guests

- Taylor Branchclose friend of Julian Bond. He is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author best known for his landmark narrative history of the civil rights era, a trilogy titled America in the King Years.

- Benjamin Jealousformer NAACP president and CEO. He’s a partner at Kapor Capital and senior fellow at the Center for American Progress.

- Richard Cohenclose friend of Julian Bond and president of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

- Eleanor Holmes Nortondelegate to Congress representing the District of Columbia. She was an organizer for SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

We remember the life of civil rights pioneer Julian Bond, who died on Saturday at the age of 75. Bond first gained prominence in 1960 when he organized a series of student sit-ins while attending Morehouse College. He went on to help found SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. After the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Bond was elected as a Democrat to the Georgia House of Representatives. But members of the Legislature refused to seat him, citing his vocal opposition to the Vietnam War. Bond took the case to the Supreme Court and won. He went on to serve 20 years in the Georgia House and Senate. At the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Julian Bond became the first African American nominated for U.S. vice president by a major political party. But he had to withdraw his name because he was just 28 years old — seven years too young to hold the second-highest elected office. Julian Bond would go on to co-found the Southern Poverty Law Center. He served as the organization’s first president from 1971 to 1979. From 1998 to 2010, he was chairman of the NAACP. We speak to Eleanor Holmes Norton, delegate to Congress representing the District of Columbia; former NAACP president Benjamin Jealous; Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Taylor Branch; and Richard Cohen, president of the Southern Poverty Law Center. “He never thought the movement was about only blacks, so he was easily able to grapple with the movement that involved women, that involved the LGBTQ community, that involved climate change,” said Norton.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Today, in a Democracy Now! special, we remember the life of civil rights pioneer Julian Bond, who died Saturday at the age of 75. Julian Bond first gained prominence in 1960 when he organized a series of student sit-ins while attending Morehouse College. He went on to help found SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. After the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Bond was elected as a Democrat to the Georgia House of Representatives. But members of the Legislature refused to seat him, citing his vocal opposition to the Vietnam War. Bond took the case to the Supreme Court and won. He went on to serve 20 years in the Georgia House and Senate. At the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Julian Bond became the first African-American person nominated for U.S. vice president by a major political party, but he had to withdraw his name because he was just 28 years old—seven years too young to hold the second-highest elected office. Julian Bond would go on to co-found the Southern Poverty Law Center. He served as the SPLC’s president from 1971 to ’79. From 1998 to 2010, he was chair of the NAACP.

In a statement, President Obama said, quote, “Julian Bond was a hero and, I’m privileged to say, a friend. Justice and equality was the mission that spanned his life. Julian Bond helped change this country for the better,” President Obama wrote.

Julian Bond appeared on Democracy Now! in 2009 as the NAACP was celebrating its 100th year. I asked him to talk about how he joined the NAACP.

JULIAN BOND: Well, I joined the NAACP when I was in college at Morehouse College in Atlanta, and was sporadically active with it for a number of years after that. And then, after the collapse of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, I became active again in Atlanta, became president of the Atlanta branch, eventually was elected to the NAACP board of directors, and 11 years ago was elected the NAACP chairman. And I’ll be stepping down from that in February of next year.

AMY GOODMAN: One quick question.

JULIAN BOND: Sure.

AMY GOODMAN: Were you a student of Dr. King, actually in his class?

JULIAN BOND: Yes, I’m actually one of the few people, six people in the whole world, who honestly can say I was a student of Martin Luther King’s. He taught one time, one class at Morehouse College. I believe there were six Morehouse college students—Morehouse is all-male—two Spelman College students, all female. So there were eight of us—six or eight of us in the class. And we’re the only people who can say, “I was a student of Dr. King’s.” So, yes, I was.

AMY GOODMAN: And what do you remember of that class?

JULIAN BOND: I remember that it was a philosophy class that he co-taught with the man who taught him philosophy when he was a student at Morehouse College. And I remember that, actually, we didn’t talk about philosophy much, but he reminisced about the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which was then just a few years earlier. He talked about the civil rights movement.

And, you know, I’m so mad at myself, and I think all the rest of us, because to us this was not as extraordinary as it may sound today, that this was just a conversation between teacher and students, and the idea of writing it down, the idea of recording it, never entered any of our minds. And I’ve asked my colleagues, my fellow students who were in the class with me, what notes they took, what they remember, and none of us did that. But luckily, one of my colleagues, Reverend Amos Brown, who’s now pastor of a church in San Francisco and on the NAACP board, he has gotten copies of Dr. King’s notes, the notes he used in that class. And I have my own copy of those. And so, I get some idea of what he hoped to talk about in the class, but almost never did.

AMY GOODMAN: Julian Bond speaking in 2009 around the 100th anniversary of the NAACP, which he chaired at the time. Julian Bond died on Saturday in Fort Walton, Florida, at the age of 75. His wife said he died of complications from vascular disease. It was just a brief illness.

Today, we spend the hour looking at the life and legacy of Julian Bond. We’ll have a roundtable. We’re joined by Eleanor Holmes Norton, delegate to Congress representing the District of Columbia; former NAACP head Ben Jealous; Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Taylor Branch; and Richard Cohen, president of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

I want to go to Taylor Branch first in Baltimore. Taylor, when did you first meet Julian Bond?

TAYLOR BRANCH: I first met him in 1968, when he was the boy wonder that we looked up to because he had been seated in the Georgia House of Representatives out of the civil rights movement. I was only 21, but there was a plan afoot to try to challenge the segregationist delegation at the Democratic convention of Lester Maddox, and modeled on the Mississippi Freedom Democratic challenge in 1964. And out of that became—grew a great adventure of traveling around, forming a challenge delegation. Julian went up to Chicago to argue before the credentials committee as the representative. My job was to get him to head this delegation. And he did. And we went up there, and to everyone’s shock and surprise, our delegation was seated in the Democratic convention. That was part of your introduction. So, I was like his gopher. I always joked that I ironed his shirts, while he was giving press conferences and really mesmerizing the world with his good humor and his patriotism and his principles, so much so that the convention got carried away and nominated him for vice president.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, talk about what this meant that he was nominated for vice president at the ripe old age of—was it 28?

TAYLOR BRANCH: He was 28, I was 21. We had the same birthday, which we celebrated together. We were both born on January 14th, the day before Dr. King. I was only 21.

What it really meant—1968, as younger viewers may not remember, was a crucible year. That was the year when Dr. King had just been shot, when Robert Kennedy was shot that summer two months later, and the world was kind of coming apart over Vietnam. To have a convention in that year, in which, out of all of this chaos over Vietnam and everything, you had this very handsome young boy—young man with a mellifluous voice representing a diverse delegation from the state of Georgia, that then had a segregationist governor, Lester Maddox, nominated—appointed. It was grossly undemocratic. He appointed all the delegates. They were all white, and, as I remember, they were nearly all male. It’s a different world. But Julian spoke for the world that we actually have in conventions now, where they’re representative and they represent the people. And it was so out of joint, but he was infectious. And the whole country kind of got carried away with that, to the point that somebody stood up and nominated him for vice president.

Julian was always vastly amused by that. What he really enjoyed about it was not so much that they nominated him, but that he was too young to be nominated. And he savored that for the rest of his life. But it made him a media phenomenon and a lecturer around the country about the larger issues of justice for the rest of his life.

AMY GOODMAN: In 1967, Julian Bond spoke out against the Vietnam War during an interview on the TV station KVOS.

JULIAN BOND: My position is that things that the United States does overseas are related to its behavior towards people inside the country and that there’s a relationship between what I consider our aggressive behavior in Vietnam and the treatment of minority groups inside the United States, that, taken separately, both are wrong, and taken together, they’re even wronger. I imagine that—or rather, I am of the opinion that our involvement in Vietnam is wrong, it’s illegal, it’s immoral, it’s un-Christian, it’s un-Buddhist, it’s un-Jewish, it’s un-Catholic; we ought not be there; we ought to disengage ourselves; and that there will never be decent treatment for minority peoples in this country until we begin to concentrate on freedom and justice and equality for those at home, and stop worrying about puppet dictatorships and despotic governments in Southeast Asia.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Julian Bond in 1967. We’re talking to Taylor Branch, close friend of Julian Bond, also a Pulitzer Prize-winning author, best known for—best known for his landmark narrative history of the civil rights era, a trilogy entitled America in the King Years. So this opposition to the Vietnam War, not only a crusader on civil rights, affected him being able to be in the Georgia state Legislature. Is that right, Taylor Branch?

TAYLOR BRANCH: Yes. Actually, in the year before that, in 1966, he was—after he was elected to the Georgia House, he still remained the communications director of SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. And when that organization issued its first statement against the Vietnam War, Julian read it, not as his statement, but as the statement of SNCC. And it got a lot of publicity, and the Georgia House rose up and said, “Even though he’s elected, we will not permit him to take a seat, because he’s against this war.” So, he came into the position through the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee that said this war is wrong when we have so many evils here, and, in effect, it’s a neocolonial war. The cadence of that interview that you just played sounded a little bit like Julian—he sounded a little bit like Dr. King there. It didn’t have the normal lilt of Julian, but that’s because this was a very, very serious issue that was tearing the country apart at the time, and he was trying to be as sober as he could.

AMY GOODMAN: We are going to continue our conversation with a rolling roundtable. Taylor Branch, please stay with us in Baltimore, close friend of Julian Bond, the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, best known for his landmark narrative history of the civil rights era, the trilogy of books titled America in the King Years. We’ll be joined by Ben Jealous, former head of the NAACP, which Julian Bond chaired for years; Eleanor Holmes Norton, who worked closely with Julian Bond. We’ll also be talking with Richard Cohen, who is a friend of Julian Bond, just had dinner with him a few nights before he died, president of the Southern Poverty Law Center. He will be joining us from Montgomery. This is Democracy Now!, as we remember Julian Bond. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “A Change Is Gonna Come,” Sam Cooke, here on Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report, as we remember Julian Bond. And for many who are just waking up to this news, it’s hard to be talking about remembering Julian Bond, who are so used to his presence on the forefront of equality and freedom in this country, whether for gay marriage, environmental rights, the civil rights movement, the antiwar movement. We’ve been talking with the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, Taylor Branch. He’s still with us from Baltimore. He was a close friend of Julian Bond. Ben Jealous will join us in a few minutes from Washington. Richard Cohen is standing by in Montgomery, Alabama, Southern Poverty Law Center, one of the organizations that Julian Bond co-founded. And Eleanor Holmes Norton is with us from Martha’s Vineyard, delegate to Congress representing the District of Columbia, organizer for SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Eleanor Holmes Norton, when did you first meet Julian Bond?

REP. ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON: I first met Julian when I was a law student, and I came to Atlanta to become a part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee on my way to Mississippi. He was one of the leaders, indeed a founder, of SNCC. SNCC had just been founded just a few years before, when Ella Baker, the great seer and godmother of the civil rights movement, suggested that students get together so that they could have a real student organization. And Julian was a multitalented member of SNCC. He was its spokesman. He was its writer. He was one of its major leaders. He was often the one you most often heard from, except whoever happened to be chairman at the time.

AMY GOODMAN: And what were you must struck by with Julian in those early years and then his trajectory of issues through the decades, as you became the congressmember, the delegate to Congress representing the District of Columbia? You worked together, too, well, probably near the end of his life. Is that right?

REP. ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON: Well, to the very end, until, indeed, just a few months ago, when he and I had an intergenerational forum with leaders from Ferguson and New York after the police shootings. That’s the Julian Bond I knew, the Julian Bond who, in his own way, never left the civil rights movement. Some of us—for example, John Lewis is my colleague in Congress—had moved on to other pursuits while still being a part of the movement. Julian never left the movement. And he redefined the movement in his own image. He never thought the movement was about only blacks, so that he was—he was easily able to grapple with the movement that involved women, that involved the LBGTQ community, that involved, yes, issues like climate change.

He used his talent as a writer and a spokesman to continue to speak throughout his life. He lived in the District of Columbia and was my constituent for the last 30 years. He became a spokesman for statehood for the District of Columbia. It seemed just so natural that Julian Bond, resident of the District of Columbia, would embrace statehood. I remember that when you got into a taxi in the District of Columbia coming in, Julian Bond’s image would come up saying, “Welcome to the District of Columbia, where we don’t have the same rights as everybody else.” And you will remember that voice, that voice that became so familiar that Julian was sometimes used to narrate civil rights stories and civil rights videos. Until the very end, he was always the spokesman, always the wordsmith, always the man of courage, always the man redefining civil rights for the moment.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re talking to Eleanor Holmes Norton, a delegate to Congress representing the District of Columbia. She’s in Martha’s Vineyard, where Julian Bond also spent time. She was a longtime organizer for SNCC decades ago. And Ben Jealous is with us in Washington, D.C. He is the former NAACP president, the youngest elected to be president of the NAACP, now a partner at Kapor Capital and senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. Ben, as Eleanor Holmes Norton talks about the trajectory of Julian Bond’s life, you were with him in those later years as he was branching out from civil rights, but never really that far—human rights, considering you were so active together on the issue of police brutality and the killing of young black men and women. Talk about what Julian and you did together.

BEN JEALOUS: Yeah, look, he was somebody who was just very clear that we had to do what was right and we had to do it now. And so, you know, we would get together, and the conversations would be very short. It would really come down to: “So, Ben, what do we need to do?” We went back to Georgia together to take on the state when they seemed so intent on killing Troy Davis, and made sure that the world knew his name, but then followed through to make sure that states whose folks had become outraged that this was still possible would go forward to abolish the death penalty in their state.

He also was someone, quite frankly, who could see around corners, who knew where the movement had to head next. He made sure that the CEO of the NAACP that he chose would be somebody who supported marriage equality, because he understood that that was a place that we had to go next. And so, as I sat next to the finalists, when I was being chosen—and there were three of us: one of us was a pastor from Dallas, Texas, one of us was a politician from Florida, both great men—we started talking about kind of what we believed in. It became clear that all three of us were folks who knew that marriage equality was an issue that we would all have to stand up for as a movement, and yet the NAACP had no policy on it at the time. That was Bond saying, “Look, this is where we have to go. If we’re going to pick somebody to be our CEO, they have to be prepared to go there with me.”

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to turn to Julian Bond speaking in 2009, a very brief comment, the clip we chose, when he spoke at a human rights campaign dinner in Los Angeles.

JULIAN BOND: Black people, of all people, should not oppose equality, and that is what gay marriage is.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Julian Bond in 2009. This is when President Obama—right around the time he was first taking office. Ben Jealous?

BEN JEALOUS: Yeah, you know, he was so smooth about it. I mean, that was the part that was so kind of seductive about Julian, I think, even for those who wanted to oppose him, is that his logic was succinct, it made sense, and he presented it in a way that you wanted to say, “Me, too.” And in the end, there were only two people on the 64-member board who voted against us. And that was absolutely because he took the time to win folks over, and when he made his case, it was very hard to say no.

AMY GOODMAN: Environmental activism, Ben Jealous?

BEN JEALOUS: You know, there was a time, when I was CEO, when I was called by Mike Brune, who is the CEO of the Sierra Club, and asked if I would lock myself to the White House gate with him to protest the Keystone pipeline. And I wanted to do it, but I knew that it would be controversial for me to do it, because we didn’t have policy and we had other issues I was expected to lead on at the moment. And so I called Julian, and Julian said, “I’ll go.” And that was what was so wonderful about him, is that he was always courageous, always willing to be on the cutting edge and always willing to help lead and willing to be part of a leadership team, and so humble while being so powerful.

You know, I said to him once, I said, “Tell me about the March on Washington.” And he was somebody who didn’t want to talk about the past much, but he indulged me. He said, “Well, Ben, you know, you have to understand what my role was.” And I said, “Well, what was your role?” He said, “Well, my role at the March on Washington was passing out Cokes to the people who were really famous.” And I said, “So what was the high point for you?” And he said, “It was when Sammy Davis Jr. looked at me, winked and snapped his finger and pointed at me and said, 'You know, kid, you're cool.”

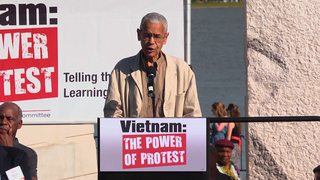

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go to 2013, Julian Bond speaking at the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington.

JULIAN BOND: I’m delighted to be here, just as I was delighted to be here 50 years ago. Then, we could not have imagined we’d be here 50 years later with a black president and a black attorney general. But that’s a measure of how far we have come.

But still we march. We march because Trayvon Martin has joined Emmett Till in the pantheon of young black martyrs. We march because the United States Supreme Court has eviscerated the Voting Rights Act, for which we fought and died. We march because every economic indicator shows gaping white-black disparities. We march for freedom from white supremacy. But still we have work to do. None of it is easy, but we have never wished our way to freedom; instead, we have always worked our way. Today we have much more to work with, and we take heart that so much has changed.

The changes that have come have everything to do with the work of the modern movement for civil rights. We must not forget that Dr. King stood before and with thousands, the people who made the mighty movement what it was. From Jamestown’s slave pens to Montgomery’s boycotted buses, these ordinary men and women labored in obscurity. And from Montgomery forward, they provided the foot soldiers of the freedom army. They shared with King an abiding faith in America. They walked in dignity rather than ride in shame. They faced bombs in Birmingham and mobs in Mississippi. They sat down at lunch counters so others could stand up. They marched, and they organized. Remember, Dr. King didn’t march from Selma to Montgomery by himself. He didn’t speak to an empty field at the March on Washington. There were thousands marching with him and before him, and thousands more who did the dirty work that preceded the triumphal march. The successful strategies of the modern movement were litigation, organization, mobilization and coalition—all aimed at creating a national constituency for civil rights.

AMY GOODMAN: Julian Bond speaking in 2013 at the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington. This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. We’ll continue remembering the life and legacy of Julian Bond after this minute.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Eyes on the Prize,” Sweet Honey in the Rock, here on Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we remember the life and legacy of Julian Bond, who died this weekend in Florida. His wife, Pamela Horowitz, said he died of complications of vascular disease.

We are joined by a roundtable of people. We were just speaking with Ben Jealous, former head of the NAACP when Julian Bond was its chair. We’re also joined by Eleanor Holmes Norton, who was a close colleague and fighter alongside Julian Bond for decades. Now she is a delegate to Congress representing the District of Columbia. She was an organizer with SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, when he was there, as well. And we’re joined by Taylor Branch, the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, best known for his landmark narrative history of the civil rights era, the trilogy titled America in the King Years, the books Parting the Waters, Pillar of Fire and At Canaan’s Edge.

Taylor Branch, can you talk about the year—what was it? 19—the year that Julian Bond ran against his close friend, his SNCC ally, John Lewis, 1986, and what happened when they ran for the same seat in Congress?

TAYLOR BRANCH: Well, it was a wrenching time for everyone who knew both of them. They were very, very different people, except that they both believed in the same cause and they were running for the same office at a time when—huge friction. And there was a longtime estrangement. John won, and he’s still in Congress from that seat nearly 30 years later. It marked a turning point in Julian’s career. He basically left politics and went into academics, much to the relief and joy of his mother. I have a story about that. But there was estrangement between John and Julian for a long time over that, and it was something that everybody in the movement lived with.

Years later, Julian and John and I both—all three of us got an honorary degree at the same school in New Orleans, Dillard University. And there was a lot of—they had not spoken, and there was a lot of tension about whether—and since I knew both of them, they were both on that delegation in 1968, I kind of mediated this meeting. And it was very funny because Julian picked a restaurant for us to go to, and it was a restaurant in New Orleans that had transvestite waiters, and one of them sat on John Lewis’s lap, just came over and sat on his lap, and John was really taken aback. And then, when the waiter left, he started laughing, and Julian started laughing, and they said, “OK, I guess we’re OK now.” They went through this experience where Julian laughed at the mortification of John Lewis, who was much less comfortable with that sort of thing than—but John had the grace to laugh back and say, “We’re all right now.” Basically, “I’m in Congress. You’re a professor at the University of Virginia. We’re all right now. We’re still in the same cause.”

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us the story of Julian Bond’s mother. Talk about his mother and his father. His dad, wasn’t he the first African-American president of the historically black college, Lincoln University?

TAYLOR BRANCH: Lincoln University, absolutely. His mother, at the 30th anniversary of Freedom Summer in 1994, Julian and Pam and I drove down together, and Julian took his mother, Julia, who’s extremely dignified, well educated, spoke in poetry almost. And she said that her greatest loss was that Julian’s father, the college president, didn’t live to see Julian become a professor at the University of Virginia, because Julian dropped out of college, which mortified his father, a college president—he dropped out of college to join the movement—and always was upset, because he was a Victorian, he believed in education, and how could his boy not finish college? But then, later, Julian came back. And his mother—his mother, down in Mississippi at the anniversary for Freedom Summer, said, “If only his father could see him now, he’d be happy now he’s back teaching.” The University of Virginia, in fact, is endowing a Julian Bond professorship in civil rights and social justice. And if people want to remember Julian Bond, they can contact the University of Virginia to help endow that chair. I think they’ve raised most of the money already, but they’re not quite there yet. But his mother was immensely proud that he became a professor, not just at the University of Virginia, but at Drexel and at Harvard and at American University toward the end of his life.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me ask you, there’s been some pushback at The New York Times obit that included the line, “Julian Bond’s great-grandmother Jane Bond was the slave mistress of a Kentucky farmer.” A number of Black Lives Matter activists and others are tweeting about this, saying “Kentucky farmer” instead of “slave master,” and “slave mistress” instead of addressing the issue of the impossibility for consent as a slave, and the whitewashing of rape.

TAYLOR BRANCH: Well, “slave mistress” is a loaded terminology, and I would agree with that criticism, because a mistress is someone who has a choice. And if you’re owned by someone, you don’t really have a choice over matters like that. It does show—you know, Julian was very light-skinned. When I first met him back in the 19—and that was all because of the privilege of the enslavers. That’s where all the light-skinned black people came from. When I first knew Julian, he was still on billboards in Georgia, because he was movie-star handsome, and he would be on Coca-Cola ads. And he used to confess that because of that terrible problem—crime—in the background of American history of—engender the most intimate moments that mixed slavery with rape, that there were a lot of problems about color within the black community. Julian told me that when he was in Morehouse College, he went to paper bag parties, where black people themselves in fraternities would nail a paper grocery bag up on the door, and if you were darker than the bag, you couldn’t get into the party. So there was color discrimination within the race. And it’s all a legacy of the great crime of slavery, which we still carry with us.

AMY GOODMAN: Richard Cohen is joining us, as well as Taylor Branch and Eleanor Holmes Norton. Richard Cohen is in Montgomery, a dear friend of Julian Bond. He’s current president of the Southern Poverty Law Center, which Julian Bond helped to found with Morris Dees. Richard Cohen, your thoughts today?

RICHARD COHEN: Well, you know, I’m amazed. I’m shocked. I had dinner with Julian and Pam just 10 days ago, and he was himself, you know, witty, talking about politics. And it’s just incredible that 10 short days later he’s left us.

AMY GOODMAN: Co-founding the Southern Poverty Law Center and the mission of the SPLC?

RICHARD COHEN: Well, you know, when the Civil Rights Acts of the 1960s were passed, they weren’t self-executing. There was still massive resistance in the Deep South. Julian understood that better than most, and so he helped establish the Southern Poverty Law Center so we could make those acts kind of a reality. He was, you know, critical to our success. Most recently, he served as a historical consultant for a film that we made about the Voting Rights Act. So he was there at the beginning, he was there for us just a few days ago. Hey, Amy, can I mention one other thing?

AMY GOODMAN: Yes, of course.

RICHARD COHEN: You know, Julian was somebody of great wit. You know, Taylor told that funny story. Julian, people recognized him from the 1968 convention. Julian hosted Saturday Night Live in 1977 and just, you know, again, that incredible combination of profundity and wit. He carried that into the political circles, as well. One of his great lines that I think I’ll never forget is—it was something like, “Obama is to the tea party as the moon is to werewolves.” And, you know, Julian had a way—he had a way with words. He was just—the country has lost something truly, truly special.

AMY GOODMAN: You know, there was just the 40th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War in Washington, and a number of the antiwar activists were being honored, all the octogenarians. And I saw Julian Bond there, and I asked someone why Julian Bond wasn’t also being honored. And they said he wasn’t old enough, that he was still a spring chicken. But, Eleanor Holmes Norton, if you could talk about the significance of Julian Bond taking on all of these different issues? I mean, long before President Obama was talking marriage equality, there was Julian Bond saying you had to treat people equally.

REP. ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON: Well, Julian’s trademark was being on the cusp. You mentioned the Vietnam War, and he wasn’t old enough. Well, we must remember that Julian was refused his seat in the Georgia Legislature after he had been elected. I was then a constitutional lawyer at the American Civil Liberties Union, and here was Julian, my colleague from SNCC, moving on into political life, and his issues, updated, were following him, because he was refused a seat because he said he opposed the Vietnam War, and he said all wars. For that, the ACLU, with me writing the amicus brief, wrote a brief to the Supreme Court—and isn’t it interesting it had to go all the way to the Supreme Court?—to argue that it was a denial of Julian’s free speech to deny him his seat because he spoke out against the war. Speaking out against the war was [inaudible]. Julian was nonviolent in the truest sense of the word. In many ways, he considered himself a pacifist.

AMY GOODMAN: Did he weigh in with President Obama, who calls Julian Bond a close friend, around the issue of war?

REP. ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON: Whether around the issue of war or not, he became friendly with the president, because the president was a great admirer of Julian. And Julian was a supporter of the president, not always—not always uncritical, but always supporting.

AMY GOODMAN: In 2013, Julian Bond’s grandchildren, Reece McMillan and Jacob Bond, recorded an interview with their grandfather, with Julian Bond, and asked him about his experience in the civil rights movement.

REECE McMILLAN: Granddad, what made to join the civil rights movement?

JULIAN BOND: It was tremendously exciting, because we felt we were doing wonderful work. We felt we were changing the country for the better, and that even though it was hard work and sometimes dangerous work, we were happy to do it and eager to do it. And I’m still very close to the people who did that with me today, even closer than I am with the people I went to high school or college. I’m closer with the people I was in the movement with.

JACOB BOND: Did you ever think that getting arrested was not the right way to go about getting change?

JULIAN BOND: We debated about this question over and over and over again, and usually came out with the feeling that it was the right thing to do. I took a group of students, men and women, from the colleges in Atlanta down to the City Hall, and we went into the cafeteria, and the first thing we saw was these black women behind steam tables where the food was. And they were looking at us with fear and admiration, fear because they knew why we were there—we were going to sit in, that meant police would be called—admiration because they had read about this happening in other places north of Atlanta, and so they were happy it was happening here and they were able to witness it themselves. So we got our food. We went up to the cashier, a white woman, and she said, “I’m awfully sorry. This is for City Hall employees only.” And I said, “You have a big sign out on the street here that says, 'City Hall cafeteria, the public is welcome.'” She said, “We don’t mean it.” I said, “Well, we’ll stand here until you do.” And she called the police, and the police came and arrested us and took us away. And that’s how I got arrested the first time.

AMY GOODMAN: Taylor Branch, your thoughts on this first arrest, as Julian Bond talks to his grandchildren?

TAYLOR BRANCH: That’s March 15th, I think—no, the ad was the 15th, it’s a couple days later—of 1960. That’s only six weeks after the sit-ins started on February 1st in Greensboro. They spread like wildfire through the South and finally got to Atlanta, which was a bastion of middle-class gentility. Julian, what he didn’t tell his grandchildren was that’s the only time he got really arrested. He did not like going to jail and would always joke about the fact that his role in the civil rights movement, after going to jail, was to do the press releases and to defend all the other people who went to jail. He had that sense of humility and that sense of grace, combined with the tremendous respect for the courage it took to go to jail over and over again. I think that’s the nature of the underlying bond between him and John Lewis, that John Lewis would—kept going to jail, and Julian’s role was to be the spokesman with the great voice who would justify what he was doing.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to end with Julian Bond in his own words in 2009 on Democracy Now! on the 100th anniversary of the NAACP, which he chaired at the time.

AMY GOODMAN: Your thoughts on one of the many controversies going on today, swimming pool in Philadelphia that didn’t want black children swimming there, this controversy brewing as the NAACP is celebrating 100 years?

JULIAN BOND: It’s brewing not only as the NAACP is celebrating its 100 years, but as people are saying, “Why do we need this organization? Why do we need the NAA—why do we need somebody fighting racial discrimination? Barack Obama is president, and so all discrimination has just disappeared and vanished.”

But our new CEO, 36-year-old Ben Jealous, said, “We’ve come to a point where the president of the United States is black and can walk through the front door of his airplane, but his children can’t swim at a pool in Philadelphia.” And so, if that doesn’t show you why we need the NAACP, I don’t know what would.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about what you’re taking on right now, what the NAACP is doing at a hundred.

JULIAN BOND: Well, we—you know, when I heard Obama talking in the bit you played just a moment ago, it’s so odd how he summoned up what we used to do as—and it’s what we do right now: We fight racial discrimination. I’m constantly asked, “What new thing is the NAACP doing?” because Americans like new things, you know. They want you to do something new every year. We do the same thing. We do it in new years. We fight racial discrimination. We engage in coalition, in litigation, in agitation. That’s what we do. We do it every day all across the country, in small towns and big cities. And we run into incidents like this Philadelphia thing.

AMY GOODMAN: Julian Bond speaking in 2009. He died on August 15th, 2015, just a few days ago. That does it for our show. Thanks to Eleanor Holmes Norton and to Taylor Branch, to Richard Cohen and to Ben Jealous.

Media Options