Topics

Guests

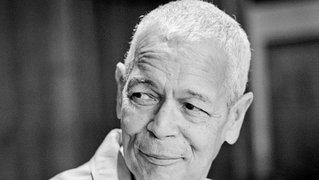

- Julian Bondleading civil rights activist, co-founder of SNCC and former chair of the board of the NAACP.

In one of his final speeches, the late civil rights leader Julian Bond spoke at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on May 2, 2015, as part of the “Vietnam: Power of Protest” conference. He was introduced by the actor and activist Danny Glover. Julian Bond died on August 15 at the age of 75. Bond first gained prominence in 1960 when he organized a series of student sit-ins while attending Morehouse College. He went on to help found SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Julian Bond would go on to co-found the Southern Poverty Law Center. He served as the organization’s first president from 1971 to 1979. From 1998 to 2010, he was chairman of the NAACP.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: As we wrap up our show today, well, we’re beginning this—we are ending this week where we began this week, and that’s remembering the late, great civil rights leader Julian Bond, who died on August 15th at the age of 75. In May, Julian Bond spoke at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial as part of the “Vietnam: Power of Protest” conference. Both Juan and I were at this event. Afterwards, people marched to the Martin Luther King Memorial. It was one of Julian Bond’s last public speeches. He was introduced by the actor and activist Danny Glover.

DANNY GLOVER: Julian Bond, at the age of 20, helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and then kept making history wherever he went. He was elected to the Georgia state House of Representatives in 1965, but members of the House refused to seat him because he opposed the war in Vietnam. In 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the House had denied his freedom of speech and had to seat him. From 1965 to 1975, he served in the House, Georgia House, and served six terms in the Georgia state Senate from 1975 to 1986. He recently served as chair of the NAACP. I have the honor, distinct honor, of welcoming Julian Bond.

JULIAN BOND: Thank you. Thank you a great deal. Thank you. Thank you for this kind welcome.

It’s fitting that we should have come to this place. Dr. King believed that peace and the civil rights movement are tied inextricably together, that the people who are working for civil rights are working for peace, and that the people working for peace are working for civil rights and justice. Accordingly, on April 4th, 1967, King delivered his famous speech against the Vietnam War. This was not without risk, because the mainstream press immediately denounced his speech, including The New York Times, The Washington Post and Life magazine. King was compelled to speak out, he said, because, one, the cost of war made its undertaking the enemy of the poor; two, because poor blacks were disproportionately fighting and dying; and, three, because the message of nonviolence is undermined when, in King’s words, the United States government is “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world.” Georgia asked me if that was on this memorial. It’s not.

The organization of which I was a part in 1960, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, also felt compelled to speak out against the war, a year before King did so. In January 1966, Samuel Younge Jr., a Tuskegee Institute student and a colleague in SNCC, went to a civil rights demonstration in his hometown Tuskegee. He needed to use the bathroom more than most, because during his Navy service, including the Cuban blockade, he had lost a kidney. When he tried to use the segregated bathroom at a Tuskegee service station, the owner shot him in the back. The irony of Sammy losing his life after losing his kidney in service to his country prompted SNCC to issue an antiwar statement. We became the first organization to link the prosecution of the Vietnam War with the persecution of blacks at home. We issued a statement which accused the United States of deception in its claims of concern for the freedom of colored people in such countries as the Dominican Republic, the Congo, South Africa, Rhodesia and in the United States itself. We said, “The United States is no respecter of persons or laws when such persons or laws run counter to its needs and desires.” This, too, was not without risk.

I was SNCC’s communication director and had just been elected to my first term in the Georgia House of Representatives. When I appeared to take the oath of office, hostility from white legislators was nearly absolute. They prevented me from taking the oath and declared my seat vacant. I ran for the vacancy, and I won again. And the Legislature declared my seat vacant again. My constituents elected me a third time, and the Legislature declared my seat vacant a third time. It would take a unanimous decision by the Supreme Court before I was allowed to take my seat. As King counseled, every man of humane convictions must decide on the protest that best suits his convictions, but we all must protest. And protest we did. And in so doing, we helped to end the war, and we changed history.

Now we have both a Vietnam Memorial and a Martin Luther King Memorial. But we don’t tell the truth about either. As Tom Hayden has written, “the worst aspects of the Vietnam policy are being recycled instead of reconsidered.” I urge you to read his Forgotten Power of [the] Vietnam Protest. We refused to allow the Vietnamese to vote for reunification in 1956, for fear they would vote for Ho Chi Minh. Many people still sadly believe the pervasive postwar myth that veterans returning home from Vietnam were commonly spat upon by protesters. As Christian Appy says, “it became an article of faith that the most shameful aspect of the Vietnam War was the nation’s failure to embrace and honor its returning soldiers.” Honoring returning soldiers doesn’t make the war honorable, be it Vietnam or Afghanistan or Iraq. And the best way to honor our soldiers is to bring them safely home. As James Fallows writes, “regarding [military] members as heroes makes up for committing them to unending, unwinnable missions.” The Pentagon has chosen to commemorate the Vietnam War as a multiyear, multidollar thank you, because, as Afghan vet Rory Fanning said, “Thank yous to heroes discourage dissent.”

We practiced dissent then. We must practice dissent now. We must, as Dr. King taught us, “move beyond the prophesying of smooth patriotism to the high grounds of a firm dissent based upon the mandates of conscience and the reading of history.” As King said then, and as even more true now, “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.”

I want to close as King closes the Vietnam speech, with an excerpt from James Russell Lowell’s “The Present Crisis.” He wrote:

“Once to every man and nation comes the moment to decide,

In the strife of Truth with Falsehood, for the good or evil side;

Some great cause, God’s new Messiah, offering each the bloom or blight,

And the choice goes by forever ’twixt that darkness and the light.

“Though the cause of Evil prosper, yet ’tis Truth alone is strong,

Though her portion be the scaffold, and upon the throne be Wrong,

Yet the scaffold sways the future, and, behind the dim unknown,

Standeth God within the shadow, keeping watch above his own!”

I wish us the right choice. Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: Civil rights leader Julian Bond, speaking in May at the “Vietnam: Power of Protest” conference in Washington at the Martin Luther King Memorial. It was one of his last public speeches. Julian Bond died August 15th at the age of 75. At the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Julian Bond became the first African American nominated for U.S. vice president by a major political party, but he had to withdraw his name because he was just 28 years old, seven years too young to hold the second-highest elected office. If you want to see our hour special remembering the life and legacy of Julian Bond, visit democracynow.org.

Media Options