Related

Topics

Guests

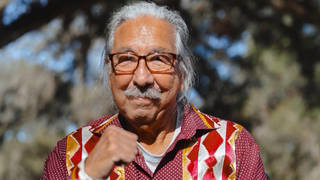

- Ed Garveyformer scientist with Exxon, where he helped start the company’s greenhouse gas research program. He is now a technical vice president at the consulting firm Louis Berger, working in environmental cleanup.

- Neela Banerjeereporter for the Pulitzer Prize-winning InsideClimate News.

A new report by InsideClimate News reveals how oil giant ExxonMobil’s own research confirmed the role of fossil fuels in global warming decades ago. By 1977, Exxon’s own senior experts had begun to warn the burning of fossil fuels could pose a threat to humanity. At first, Exxon launched an ambitious research program, outfitting a supertanker with instruments to study carbon dioxide in the air and ocean. But toward the end of the 1980s, Exxon changed course and shifted to the forefront of climate change denial. Since the 1990s, it has spent millions of dollars funding efforts to reject the science its own experts knew of decades ago.

Transcript

NERMEEN SHAIKH: One major theme of Pope Francis’s visit to the U.S. is climate change. Since he issued his historic encyclical on the environment in June, Pope Francis has made his mark as a leading voice in the climate movement. He addressed the issue at the White House on Wednesday.

POPE FRANCIS: It seems clear to me also that climate change is a problem which can no longer be left to a future generation. When it comes to the care of our “common home,” we are living at a critical moment of history.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: But long before Pope Francis started his ascent through the ranks of the Catholic Church, there was another leader in the climate movement, and one you might least expect—Exxon. Now, ExxonMobil, the oil giant, is recognized by the environmental community as one of the worst offenders on environmental issues. Environmental disasters, from the 2013 Pegasus tar sands pipeline rupture to the 1989 Valdez oil spill, have made the company a leading target of environmentalists, as has its funding for climate change deniers and its backing of organizations, including the American Enterprise Institute and the American Legislative Exchange Council, known for opposing the Kyoto Protocol and other environmental regulations.

AMY GOODMAN: But a new investigative series by the Pulitzer Prize-winning news organization InsideClimate[News].org has uncovered that decades ago, Exxon was actually on the cutting edge of climate research. Here’s a clip from the PBS series Frontline, which partnered with InsideClimate News on the project.

NEELA BANERJEE: We found the trail of documents that go back to 1977. Exxon knew carbon dioxide was increasing in the atmosphere, that combustion of fossil fuel is driving it, and that this posed a threat to Exxon. At that time, Exxon understood very quickly that governments would probably take action to reduce fossil fuel consumption. They’re smart people, great scientists, and they saw the writing on the wall.

NARRATION: One Exxon research project outfitted an oil tanker with equipment to measure CO2 levels in the atmosphere and the ocean.

ED GARVEY: We were collecting data, the southern Atlantic, the Gulf of Mexico and the western Indian Ocean. Basically every hour, we would get several measurements. So we had—I called it a data monster.

NARRATION: Today Exxon says the study had nothing to do with CO2 emissions. But scientists involved remember it differently.

ED GARVEY: We were committed. We were doing some serious science. It was a significant budget, I would say on the scale of a million dollars a year. I mean, that was a lot of money in 1979.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Ed Garvey. From '78 to ’83, he was a researcher at Exxon, where he helped start the company's greenhouse gas research program. He’s now a technical vice president at the consulting firm Louis Berger, where he works on issues of environmental cleanup. Also with us is Neela Banerjee, Washington-based reporter for InsideClimate News, one of the reporters on this recent exposé on Exxon.

Welcome to Democracy Now! Neela, let’s start with you—why you did this series and what Exxon knew and when they knew it?

NEELA BANERJEE: We started looking into early climate change research and became aware that oil companies—at least initially, it was BP, but that was later, in the '90s—had their own scientists who were looking into this. We then found out from American scientists, government scientists, who had been involved in climate research in the ’80s that Exxon was involved. And what ended up happening was that I got a transcript of a 1979 congressional hearing on climate change and tried to see if somebody from Exxon was there, and I found a gentleman named Henry Shaw. Henry was Ed's boss and was the primary researcher with that tanker project. And through him and, you know, papers that he worked on, we found other names, we found documents in archives.

And slowly we amassed this picture of a company that was clearly aware of the science, of the emerging science of carbon dioxide research, and what the scientists were saying, that it was largely driven by fossil fuel emissions. And they were smart enough to know that this could mean some kind of policy response farther down the road. And so, to deal with that, they decided to take a constructive role, and that is to do really good science so that they would be taken seriously in any future policy discussion.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: And, Ed Garvey, can you talk about when you first arrived at Exxon and the research that you did there? It’s an extraordinary finding. 1977, that’s almost 40 years ago that Exxon itself was aware of the climate impact of fossil fuel.

ED GARVEY: I was hired in 1978 by Henry Shaw specifically to begin the tanker study. He hired me explicitly—directly out of school. I was a 22-year-old chemical engineer, but he hired me directly out of school to begin to engineer, if you would, and design a system that could work on an oil tanker to study oceanic levels of CO2. The idea was to study what the ocean was doing in response to the atmosphere, so we could figure out where CO2 from fossil fuels was ending up.

AMY GOODMAN: And what did you find?

ED GARVEY: Well, we didn’t get that far along in terms of the data analysis. I mean, ultimately, we found—we estimated the amount of CO2 that was coming out of the oceans in the Equator. My thesis adviser at the time, Taro Takahashi, used that data, along with others, other data, to estimate the amount of absorption by the ocean in the poles, amount of degassing in the equatorial area. And together, he was able to estimate the carbon balance, if you would, around the ocean, the atmosphere and the biosphere.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: But why was Exxon—from what you understand, why was Exxon interested in doing this research then?

ED GARVEY: It was very much a—they saw it as a leadership role, in many respects. The goal was that if Exxon—given the importance of the problem, Exxon wanted to be at the table in terms of the discussion. The best way to be considered viable in terms of your opinion at the table was to be doing real research. And in fact, we linked up with some of the best researchers in the world at the time regarding CO2 and the global carbon cycle.

AMY GOODMAN: You were working with Columbia University?

ED GARVEY: That’s right, as well—

AMY GOODMAN: When—yes, go ahead.

ED GARVEY: As well as the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

AMY GOODMAN: When did you start to feel a change in attitude at Exxon about the work you were doing?

ED GARVEY: For me, it came very suddenly toward the end of my career there. It was gung ho for three-and-a-half years, and then the bottom fell out of the oil market, and it really changed. They just basically dropped the project. We had collected a lot of data, but hadn’t processed it to the point of understanding the information. We just had a lot of information. Columbia went on to process the data after my work there.

AMY GOODMAN: Neela Banerjee, can you talk about this turnaround, when Exxon stopped the study, what they started to understand, and how they tried to cover it up?

NEELA BANERJEE: Well, when Ed’s project was dropped, from the documents we have and, you know, talking to Ed, too, it was mainly because of financial reasons. Exxon did not stop its climate research. After it started the tanker project in '78, ’79, in 1980 it hired a lot of mathematicians to do climate modeling, because models were primitive and they were relying on other people's models and they wanted to do that in-house. So, even though the tanker project, which was relatively expensive, had ended, Exxon continued very good, rigorous, peer-reviewed climate research, mainly through climate modeling, from 1980 onward. And our documents go through 1986. And one does not notice the kind of attitude shift that appeared in the 1990s, of stalling action on climate change and so on, in that period. Exxon was still committed to doing really good science. It was just different from the tanker project. If that was empirical, this was modeling.

And then, you know, the first indication that I think all of us—not just InsideClimate News, but the world—have of Exxon’s attitude on climate change shifting was in 1989 when a group called the Global Climate Coalition was formed. And that was a group of fossil fuel companies, major manufacturers, Americans largely, that wanted to stall action on climate change. They saw that the U.N. was meeting and thinking about a policy response that countries should adopt to cut emissions of carbon dioxide. So, what happened in that '86-to-'89 period, we don’t know. You know, we can’t document a shift in thinking. There’s some speculation about the attitudes of the people who were in leadership then. They were different than the people who were in leadership in the '70s. But what we have is not an example of a cover-up—it's quite the opposite. What we have is an example of a company that used its resources as one of the biggest energy companies in the world to do really good research.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Neela Banerjee, could you say a little more about this Global Climate Coalition and what Exxon’s role within it came to be and how it’s impacted the kind of research that’s done on climate change?

NEELA BANERJEE: Well, the Global Climate Coalition, I mean, it sounds very green. I remember thinking, “Oh, this must be a group of companies that actually support action on climate change.” But it was led mainly by the auto—I mean, I’m sorry, by the oil and gas industry, but some of the other members were coal companies, auto companies and so on. And Exxon was probably the leader in the oil industry, working with the American Petroleum Institute, which is the main oil industry lobby.

And they didn’t take the approach that a lot of people who denied climate change did. And in fact, there’s in public circulation, long before we did this project, a primer that a scientist had written for members about how to talk about climate change. What he recommended was not to use the arguments that other climate deniers use, such as, you know, that it’s sunspots or natural cycles, but instead to focus on the uncertainty of the science and the models, just to hammer away at that. And indeed, people who met Exxon representatives at U.N. conferences and other climate conferences didn’t see them as sort of out-and-out deniers. Instead, they said, you know, Exxon just focused on the uncertainty of the science and used that as a way to seed doubt about the process. So that affects public opinion.

But also Exxon and others funded an infrastructure of think tanks and scientists and others who created—who issued reports and did studies that also spread doubt about climate change. And that provided the fodder for companies such as Exxon and also for policymakers to say, “Look, you know, here are these credible institutions issuing these reports. There is no consensus on climate change,” which is—what’s so unusual or sort of stark about that, now that we have these documents, is that Exxon in the ’80s was talking about a consensus among scientists about climate change and fossil fuels, and, you know, 10, 15, 20 years later, they were saying the exact opposite.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Ed Garvey, as Exxon started funding these climate denier groups, your thoughts, as we wrap up?

ED GARVEY: I just think it was an opportunity that was missed, that having developed this knowledge in-house, Exxon was in position to lead the discussion as how to deal with the problem, and instead they really chose to deny the problem. And I think that was really a missed opportunity.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Neela Banerjee, the chief executives at Exxon who became the climate deniers?

NEELA BANERJEE: Well, we don’t know what their original thinking was, but we do know that Lee Raymond, who became chairman and CEO and made seminal speeches denying climate change, was exposed to thinking about CO2 and how it affected Exxon’s business projects, including the decision to delay action on a major gas field that Exxon had picked up the rights to develop in the 1980s. So, it wasn’t that these men were ignorant of the science, but, you know, what their attitudes were when they were exposed to it, whether there was actually any kind of shift, whether it was natural or calculated, we don’t know.

AMY GOODMAN: Neela, we’re going to have to leave it there, but we’ll continue the discussion. Neela Banerjee with the Pulitzer Prize-winning InsideClimate News, and Ed Garvey. We’ll link to your exposé at democracynow.org. Of course, we’ll continue to cover the pope’s trip through the United States.

Media Options