Topics

Guests

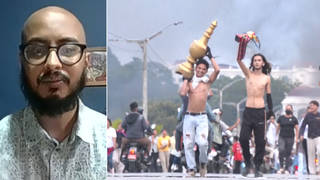

- Hamza al-Kateabdoctor and co-founder of the Al Quds Hospital in Aleppo.

- Waad Al-Kateabcitizen journalist and director of For Sama.

We continue our look at the award-winning documentary, “For Sama,” a devastating account of war-torn Syria told through the eyes of director Waad al-Kateab, who filmed hundreds of hours of footage in her native Aleppo to create a stunning depiction of life during wartime. Amid airstrikes and attacks on hospitals, Waad falls in love with one of the last remaining doctors in Aleppo, gets married and has a baby girl, Sama, to whom the film is dedicated. When protests against the regime of President Bashar al-Assad first began in 2011, Waad al-Kateab was a young economics student who began filming on a cellphone. For five years, she documented her own life and the lives of those around her as the Assad regime intensified its brutal response to the uprising. She eventually gathered hundreds of hours of footage. Ahead of the film’s release in the U.S. next Thursday, we speak with Waad al-Kateab and her husband Hamza al-Kateab, a doctor and the co-founder and former director of the Al Quds Hospital in Aleppo.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We’re continuing with the award-winning documentary feature titled For Sama, a devastating account of war-torn Syria told through the eyes of director Waad al-Kateab. She filmed hundreds of hours of hours of footage in her native Aleppo to create a stunning depiction of life during wartime. Amid airstrikes and attacks on hospitals, Waad falls in love with one of the last remaining doctors in Aleppo. She gets married and has a baby girl, Sama, to whom the film is dedicated.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re joined right now in New York by the director, Waad al-Kateab, as well as her husband, Dr. Hamza al-Kateab, who is the co-founder and former director of the Al Quds Hospital in Aleppo. He, as Waad’s husband, features prominently in the film. They’re joining us for Part 2 of our discussion about the film and the war it documents.

We want to talk about Aleppo. What is this place? And why does it matter so much to not only you, but to the president of Syria, Bashar al-Assad? And what do you think are the lies that are told about Aleppo? Let’s start with you, Hamza.

DR. HAMZA AL-KATEAB: Aleppo, mostly, like it’s the economic capital in Syria, and it’s the second-large city, after Damascus. And so, I think that’s why it’s maybe politically important to—in Syria. Maybe like Benghazi in Libya, if we want to compare.

And regarding the lies, I think the propaganda has led the conflict to be between al-Assad and the Russians against terrorist groups, ISIS, al-Nusra. And like through all the years, like in 2015, nobody was saying anything about a revolution, about like civilians who are protesting, what happened to those people. All the focus of the media was about beheading people, the ISIS, and the Russians and the Syrians fighting those people.

I think that was the most, like, depressing—or, depressing part for me as a Syrian, to be like ignored from all the Western media, and not mentioning anything about me. And even all the interviews that I did like in 2015 was like: “Are you treating ISIS? What are you doing in Aleppo? Who’s there?” While, like, ISIS was in Aleppo for only five months, and it was defeated by the Syrian opposition, the FSA, the Free Syrian Army, not even al-Assad. They were like kicked out of Aleppo at the beginning of 2014. And like nobody in the Western media said that. Nobody said that the Free Syrian Army was fighting ISIS. So, yeah.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, Aleppo, just to give also the historical significance of Aleppo, Aleppo is one of the world’s oldest, if not the oldest, continuously inhabited city in the world. And the Old City was a UNESCO—is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and much of it has been destroyed in this war. Now, Hamza, you were working as a doctor in Aleppo in 2016 when there was reportedly a chlorine gas attack. There are clips in the film where you see children and adults wearing gas masks. Now, there was some uncertainty about whether there was in fact a gas attack at that time and who was responsible for it. What do you know of what happened?

DR. HAMZA AL-KATEAB: We heard that there was an attack in a near neighborhood. And then, when the casualties, the people started to rush into the hospital, you immediately can tell by the weird smell of the people’s clothes. And it was just like the—it was just chlorine. And we started immediately to get rid of the people’s clothes, wash them, and then start to just examine their respiratory system and try to give them oxygen. This is the only thing that we could do. And the most, like, frustrating thing that the [inaudible] WHO or the U.N. or Security Council, they’re always like uncertain about who does this. Like, when Al Quds Hospital was attacked in April 2016, and it was like obviously attacked by an aircraft, all the reports and the statements by WHO, by the U.N., by the Security Council was the hospital was attacked. Like, they are not sure who attacked it. And there are only like aircrafts there by—they can tell exactly what aircrafts were flying at that day. Like, we know that governments can do this. But they’re still like not sure about anything—who do the beheading, what the opposition are doing. They’re not sure about al-Assad’s crimes. And, like, it’s very weird that now, in 2019, we’re still trying to prove al-Assad’s brutality and al-Assad’s crimes, that was filmed and shown by everyone.

WAAD AL-KATEAB: And it’s also—I really—the same, like it’s shocked when you feel that all the governments around, they’re just watching this. No one can really take a responsibility about this. And if we just went back to the main problem between Russia and the U.S., and you see that this is the main problem, which we are, as Syrians, made surprised about. And it’s more about, you know, like, OK, we speak—al-Assad is an animal, but no one can really do something to stop shelling people or—it’s more about just, you know, like taking these words back and forward between, like, leaders of the world and Assad. But on the ground, really, no one did any real action to protect people.

AMY GOODMAN: Waad, you have said, “Stop listening to the propaganda of the regime. This is not a war. This is a revolution.”

WAAD AL-KATEAB: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Describe what’s happening right now in Syria.

WAAD AL-KATEAB: It’s like—it’s still revolution. And it’s this just the result of the violence which was happening through all the years. It’s also the result that all the governments and the leadership around the world, they were just ignoring what was happening. They were more give us some solidarity with some words, but no real action. Like, the Russians interfere with Syria, and they give the regime all the support to killing people, while the other governments, they just were about, you know, like, “OK, we will give you some aid for medical stuff or some food.” But we don’t need food. We don’t need medical stuff. We need to stop this war. And you can. And you have all the ability to stop that if you want.

And when ISIS just was very rise up, all the governments around the world, they were gathering together. They finished ISIS within a very limited time. And now it’s almost nine years, and really it’s still happening as it’s from the beginning. Now, the last area, Idlib, is still shelling and bombing. And people who were displaced from Aleppo, from al-Ghouta, from Homs, the Old City, they are all now in this place, and they have really no future to speak about. They have no safety to speak about, even a place where—you know, like non-aircraft zone or something like this.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: How many people are there in Idlib?

WAAD AL-KATEAB: It’s at least 3 million people, as also Trump said about this. It’s not just my number. It’s like just unbelievable, you know, how many people. They have the same scenario before in their cities, and they’re now just threatened to have this same result in Idlib.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about your decision to leave Aleppo, and then, ultimately, to leave Syria. And will you return?

WAAD AL-KATEAB: Unfortunately, it wasn’t our decision. And we tried to handle everything, the shelling, the bombing. And you’ve seen that through the whole film. We were struggling to not leave. And we want just to stay there, even with every bad circumstances. But we felt that this is our responsibility, and this is where we should be. But at the end, the U.N., with the Russia and Assad regime, decided that this is the great solution to save—to protect people, just to displace them out and give the area for the Russia and Assad regime. And we were just forced to displacement out. We weren’t really wanted to leave.

And then, when we left, we find out that we are in a place where really don’t know anything. And we thought no one expect, even with the displacement and the—they said about this, it’s safety—safety crossing out of Aleppo. We didn’t expect that we will make it, because even the evacuation was threatened by the Russian ones and by Assad regime many times. So we were just—have no idea that we will be still alive. And when we left, it was just shocking that, OK, now what should we do in our life? And the film was just my last battle, let’s say, against what was happening, and to tell the truth of what was going on there.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Hamza, can you talk about—there’s a moment in the film—when were you asked, and by whom, to leave Aleppo?

DR. HAMZA AL-KATEAB: There are several pushes from—like, I had several calls from a de Mistura representative from Damascus. And the only push was to—she said that clearly, that the Russians are willing to give us a safe—

AMY GOODMAN: Passage?

DR. HAMZA AL-KATEAB: Passage, a safe cross, out of Aleppo. But the only way to have this is to get a direct negotiation with them. And I was like, “But what’s your role? Like, you are the U.N. You should be negotiating this. You should be implementing this, not just pushing for the Russian solution.” But like, she said clearly that it’s a matter of like power balance, and, like, it’s not like a perfect world. We can’t just do the right thing all the time. And then there was negotiation between the Russians and the militias, the opposition militias that was there, and they have decided to evacuate the city. It was like not even—it’s not the city. It was like only around two square kilometers that was left, with all the patients and injuries and families. So, that, like, was the only solution.

And the most shocking thing, as Waad said, that the corridor was monitored by the Russian, Iranian and the Syrian regime, like the three parties that were killing those people. There was no U.N., nobody at all. There was the Syrian Red Crescent, but, like, they are helpless.

WAAD AL-KATEAB: They are a regime—they are a Assad regime organization. And Bashar al-Assad, he’s the head of the Syrian—

AMY GOODMAN: He’s a doctor himself.

WAAD AL-KATEAB: Yeah, yeah. No, he is also the head of the Syrian—

DR. HAMZA AL-KATEAB: Red Crescent.

WAAD AL-KATEAB: Red Crescent. So, you know, like, who’s we—like, who we left us for, you know?

AMY GOODMAN: So, we’re with you in your vehicle as you’re going, in the film, in For Sama. And it’s not clear, Hamza, whether you’re going to be taken out. You’re not sure—

WAAD AL-KATEAB: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: —as you’re going through the checkpoint.

DR. HAMZA AL-KATEAB: Exactly. We knew that, like, the people who crossed before us—or, the nine days of evacuation, it was stopped several times. They were shooting at the convoy several times. There are people still arrested from that day, and nobody knew anything about them. So, when we were going, like, we know that there are three checkpoints. The first one is the Russian. The second one is Iranian, and then the Syrian regime. Like—

NERMEEN SHAIKH: So, before we end, if I could just ask each of you: Do you intend to return to Syria? You were forced out.

WAAD AL-KATEAB: Yeah, of course. When the regime—when Assad regime will not be in ruling of Syria anymore, we will be like—the second moment we will be getting back.

DR. HAMZA AL-KATEAB: I just want to highlight something regarding this. Like at the moment, there are around 10 million people, Syrian people, refugees, all over the other countries. And al-Assad now, and the Russians, has claimed that they have won the war against ISIS. Al-Assad is controlling 80% of Syria. And yet, we see nobody is going on—is going back. So, it’s not just—believe me, like, the audience—it’s not like an ideal life that the refugees are living. It’s not like to—my dream, when I was a child, is not just to be a refugee in the U.K., believe me. So, it’s not like the ideal life we are living. And we’re dying to go back to our country, but not at this situation.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, the film is called For Sama, your little girl. She is now how old?

WAAD AL-KATEAB: She’s now 3-and-a-half.

AMY GOODMAN: Three-and-a-half. And you’ve had another little child.

WAAD AL-KATEAB: Yeah. She’s 2.

AMY GOODMAN: Taima.

WAAD AL-KATEAB: Yeah, Taima.

AMY GOODMAN: Two, Taima. What does Sama understand? What do you want her, since you call it For Sama, to understand?

WAAD AL-KATEAB: I just want to tell her this story. And I really don’t want to force her to understand anything. I want her, when she will grow up, to look at what’s happened, and have the story from her parents, from the people around. And just she can find out why we did this and why we really struggle our life to stay in our country, what the life that we dreamed for her to be in and what the life I hope she will live in the future in Aleppo again.

AMY GOODMAN: You say, “Will you forgive me for leaving? Will you forgive me for staying?”

WAAD AL-KATEAB: Yeah. This is the—still the last sentence, which I feel very bad to say it. I had that feeling about, yeah, I just want to leave to protect her, and I want her to be proud that I’ve tried to protect her. But same time, I was very, very, like, sad about, you know, like that she will be very sad because we just left. Maybe she wants us to be stayed there, and this is our country. This is a place where we want to live.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, this is a magnificent film for all to see. Thank you—

WAAD AL-KATEAB: Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: —for coming to the United States to present it. It’s opening all over the country, beginning in New York and Los Angeles and San Francisco. Waad al-Kateab is the director of For Sama. Hamza al-Kateab is the doctor, co-founder and former director of the Al Quds Hospital in Aleppo. They met during the filming of this, during the war in Aleppo. And they had their child, for whom the film is made—is named. It’s called For Sama.

To see Part 1 of our discussion, go to democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options