Related

The National Archives and Records Administration apologized Saturday for doctoring a photo of the 2017 Women’s March to remove criticisms of President Trump. In an exhibit called “Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote,” the National Archives had displayed a large image of the first Women’s March. But at least four signs referencing Trump had been blurred to remove his name, including a poster reading “God Hates Trump.” Signs in the photo referencing female anatomy were also blurred. The shocking revelation that the archives — which calls itself the country’s “record keeper” — had altered the image was first reported in The Washington Post last week. The National Archives initially stood by its decision to edit the photo, telling The Washington Post that the changes were made “so as not to engage in current political controversy.” But Saturday, as tens of thousands in Washington, D.C., and across the country took to the streets for the fourth Women’s March, officials at the archives were seen flipping over the image at the exhibit as an apology went up in its place. But critics say an apology is not enough. We speak with Louise Melling, deputy legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union. “The job of the National Archives is to record history. Its job is not to manipulate history … so as to obliterate critiques of the president,” Melling says.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, the National Archives and Records Administration apologized Saturday for doctoring a photo of the 2017 Women’s March to remove criticism of President Trump. The shocking revelation that the agency — which calls itself the country’s, quote, “record keeper” — had altered the image were first reported in The Washington Post last week. In an exhibit called “Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote,” the National Archives displayed a large image of the first Women’s March. But signs referencing Trump had been blurred to remove his name, including a poster reading “God Hates Trump” and another reading “Trump and GOP, hands off women.”

AMY GOODMAN: Signs in the photo referencing female anatomy were also blurred. One sign reading “If my vagina could shoot bullets, it’d be less REGULATED” had the word “vagina” blurred out. Another erased the word “pussy” from a sign reading “This Pussy Grabs Back.”

The National Archives initially stood by its decision to edit the photo, telling The Washington Post the changes were made, quote, “so as not to engage in current political controversy.” Archives spokeswoman Miriam Kleiman said, “Modifying the image was an attempt on our part to keep the focus on the records.” But Saturday, as tens of thousands in Washington, D.C., and across the country took to the streets for the fourth Women’s March, officials at the archive were seen flipping over the image at the exhibit. An apology went up in its place. It began, “We made a mistake.”

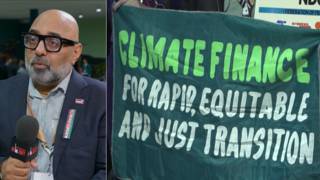

Well, for more, we’re joined in our New York studio by Louise Melling, deputy legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union.

Welcome to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with us. Respond to what’s happened. I mean, the actual head of the National Archive was an Obama appointee.

LOUISE MELLING: Good morning. Lovely to be here today. As you said, the job of the National Archives is to record history. Its job is not to manipulate history and, in particular, to manipulate history so as to obliterate critiques of the president. As you just pointed out, the archives has come out and apologized. That’s an important first move, but it’s completely insufficient. What we need now from archives is an accounting of who made this decision, why they made this decision. And really, have they done this before?

AMY GOODMAN: Oh, interesting. No, I mean, they changed the meaning of the photo.

LOUISE MELLING: Correct.

AMY GOODMAN: When you have a poster that says “God hates Trump” and you blur out “Trump,” it makes you look like someone is carrying a poster that just says “God hates.”

LOUISE MELLING: Absolutely, absolutely. I mean, they changed history. I mean, they are whiting out criticism. They are whiting out and erasing women’s bodies.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, the other aspect of this, though, is your take on their initial reasons for doing this. Even if they had some concerns, they should have at least had some kind of explanation at the exhibition or chosen a different photograph. Why not just simply choose a different photograph?

LOUISE MELLING: I can’t imagine an explanation that’s sufficient for the National Archives to doctor and alter photographs that are part of an exhibit. They’re putting up a photograph of the 2017 march. Their job, again, is — their job is to record history, to show us history. Their job is not — what they did, as you said, was to manipulate history. What they did was to obliterate criticism of the president. What they did was to obliterate references, just references, to women’s bodies, as if to say that those things are not acceptable. If we can’t trust the archives to actually be accurate, what can we trust? I mean, you were talking earlier about faith in democracy, faith in institutions. That’s essential to democracy, to our full functioning. And this is one institution, I think, where we clearly thought the job was more basic perhaps than others, like, and here they are altering photographs. It’s Orwellian.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about the fact that this is all discovered by a Washington Post reporter who goes over to the archive as the women are marching all over the country.

LOUISE MELLING: Yes, kudos to Joe Heim from The Washington Post, who reports in his Twitter account and then in a story that he had gone over to the archives researching a story, he noticed the photograph as he walked by, he noticed that there were images who blurred, checked out the credits on the photograph, went back to the office, working with a photographer from the Post who he’s credited also in his Twitter account, and then uncovers and reveals and tells us all about what happened. I mean, it’s happenstance, and thank goodness he was there. Thank goodness he did the homework, and thank goodness he publicized it.

AMY GOODMAN: And what has the archive responded to the ACLU, your demand for an explanation?

LOUISE MELLING: I have seen nothing other than the statement that it’s a mistake. And I will say, as to mistake, like, when I think about mistake, mistake is if I spilled coffee on the photo. This was an affirmative act. Somebody made an affirmative choice to blur those images so as to blur and erase criticism of the president and criticism of — you know, words like “vagina.”

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you, Louise, for joining us. Louise Melling, deputy legal director at the American Civil Liberties Union.

Media Options