Guests

- Albert Woodfoxserved the longest time in solitary confinement of any prisoner in the United States. He was held in isolation in a 6-by-9 foot cell for nearly 44 years at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola.

- Alanah Odoms Hebertexecutive director of the ACLU of Louisiana.

Louisiana faces one of the worst outbreaks of the coronavirus in the United States. New data shows black people account for 70% of all the state’s coronavirus deaths, though they comprise just 32% of the state’s population. Louisiana also has the highest incarceration rate in the country, and more than 65% of the people in its jails and prisons are black. At least 28 people are infected, and 22 corrections staff have tested positive. State corrections officials are sending infected prisoners to the Louisiana State Penitentiary — known as Angola, the largest maximum-security prison in the United States — where they are being held in Camp J, a notorious part of the prison that was shut down in 2018 because of inhumane treatment. The ACLU of Louisiana sued to stop the statewide transfer of COVID-19 patients to Angola prison, but a judge denied the request last Thursday. We speak with Alanah Odoms Hebert, executive director of the ACLU of Louisiana, and Albert Woodfox, who served the longest time in solitary confinement of any prisoner in the United States — 44 years in Angola prison. His memoir is “Solitary: Unbroken by Four Decades in Solitary Confinement. My Story of Transformation and Hope.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, broadcasting from the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States, New York City, with Juan González, who is in New Jersey, the second-most afflicted state.

But we’re turning now to Louisiana, which is facing one of the worst outbreaks of the coronavirus. New data shows African Americans account for 70% of all Louisiana’s coronavirus deaths, even as they are just 32% of the Louisiana’s population. Louisiana also has the highest incarceration rate in the United States. More than 65% of the people in its jails and prisons are black. At least 28 people are infected, and 22 corrections staff have tested positive.

State correction officials are sending infected prisoners to Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola, the largest maximum-security prison in the United States, holding them in Camp J, a notorious building that was shut down in 2018 because of inhumane treatment of the men held there. Officials have confirmed there are no ventilators at Camp J. The ACLU of Louisiana sued to stop the statewide transfer of COVID-19 patients to Angola prison, but the judge denied the request last Thursday.

This comes as a federal prison in the state, called FCI Oakdale, has already had five coronavirus deaths, more than any other federal prison. The ACLU of Louisiana has also sued to release people held there who face an elevated risk of COVID-19 infection. Their petition to the court begins, quote, “You are likely reading this Petition from self-isolation in your home. Now imagine if someone sick with COVID-19 came into your home and sealed the doors and windows behind them. That is what the Oakdale federal detention centers have done to the over 1,800 human beings currently detained there,” unquote.

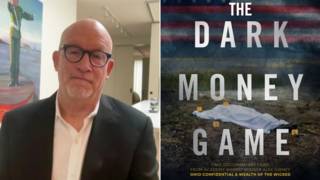

For more, we’re going to New Orleans, where we’re joined by the executive director of the ACLU of Louisiana, Alanah Odoms Hebert. Also with us and by phone is Albert Woodfox, who served the longest time in solitary confinement of any human being, any prisoner in the United States — 44 years. Known as one of the Angola Three, along with Robert King and Herman Wallace, Albert Woodfox was held in isolation for 44 years in Angola prison, convicted of killing a guard in prison, but has always maintained his innocence, said he was targeted for co-founding the first chapter of the Black Panther Party in Angola. He was released in 2016. He’s now 73 years old. His memoir is a 2019 National Book Award finalist, Solitary: Unbroken by Four Decades in Solitary Confinement. My Story of Transformation and Hope.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Albert Woodfox, let’s begin with you. Your response to the situation right now in Louisiana’s prisons, with infected prisoners being sent to this area in Angola that was called the “dungeon,” known for its inhumanity, Albert?

ALBERT WOODFOX: Well, Camp J was a — you know, Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola, consists of what’s called outcamps. Camp J is an outcamp, and it was known for — it’s a punishment program, in which prisoners that went there, they were basically denied human rights, constitutional rights. The camp itself was a horrible place to be. And I myself did nine months there, you know, and it was one of the most difficult in 44 years of solitary confinement. It was one of the most difficult times of my life.

AMY GOODMAN: And so, when you heard that infected prisoners are going to be sent there with no access to ventilators, your response?

ALBERT WOODFOX: Well, it didn’t surprise me. You know, I’ve stayed in contact with prisoners in Angola, who call and try to keep me abreast of what’s going on. Of course, I’m not allowed to visit the prison because of the 44 years of solitary confinement and my activities organizing against the corruption and the brutality that existed in Angola. So, my conversations with some of the guys I’ve talked with, you know, the prisoners are actually scared to death, because, as is the case in most prisons, the medical care in prisons is almost nonexistent. And realizing the danger of this coronavirus pandemic, they’re afraid that this virus may take hold in prison, and the damage that it could do, the death it could cause.

And, you know, I talked with — as a matter of fact, I had a conversation with somebody yesterday, and they are housing the infected prisoners at Bass Unit. It was a living quarters at Camp J. And so, my understanding, from my conversation, is that none of the staff that normally work at Angola is involved in this unit. And, you know, that’s their concern. A lot feel that the complete picture is not being told. A lot believe that more security people and civilian workers have been affected than is being reported. So, it’s a horrible situation statewide. The fact that 70% of the deaths are African-American is a national — it’s an international disgrace.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: I wanted to ask Alanah Odoms about that issue of the 70% of the more than 500 residents of Louisiana who have died who are African-American. Here in the East Coast, we don’t have yet precise figures or systematic figures. We do know in New York City, the epicenter, a borough like the Bronx, for instance, which is the most black and brown borough of the five boroughs of New York — 95% black and Latino is the Bronx — and there are already over 900 deaths in the Bronx, more than twice the number of Manhattan, the wealthiest borough of the five boroughs of the city. I’m wondering your sense in Louisiana, what is the — what can you gauge is the reason for this?

ALANAH ODOMS HEBERT: Yeah. So, I think what we’re looking at here is a systematic issue of disparity, that we have known has persisted in the African-American community for centuries. I think what you’re seeing in New York and also in other urban centers around the country is that the folks who are able to get out of the city, to move to places that are much less populated, where they can have access to fresh air, they can do social distancing more effectively, they can protect themselves and their families, they’ve done that. And the people who were not able to leave are stuck in confined situations, oftentimes in a room or a home no greater than 200 or 300 square feet with multiple family members, and are not able to do that. We saw the same thing with Hurricane Katrina. The people who were able to leave the city in advance of the hurricane did exactly that. They were able to drive. They were able to fly. They were able to protect themselves.

And this epidemic, pandemic, has laid bare the issues of disparity that have been so embedded in our country since its founding. Black and brown communities do not have the protection they need. They do not have the resources they need to protect themselves from this crisis. And moreover, their lack of access to quality healthcare and the fact that they have underlying health conditions that make them more vulnerable to this condition really cause just the perfect storm of situations that really cause dramatic loss of life.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And as far as the prisons in Louisiana or the jail systems, you’ve done studies of the situation there. There are as many as 15,000 people in Louisiana who are just being jailed awaiting trial. And has there been any success in trying to get the courts to address the coronavirus situation by releasing some people who are just awaiting trial?

ALANAH ODOMS HEBERT: Yes. So, we’ve done a landmark study looking at thousands of jail records. The study took us almost two years to do. And we determined that there are 15,000 people awaiting charge or trial in Louisiana. And of those individuals, almost 57% of those people are charged with a low-level, nonviolent offense.

And we have reason to believe that the only reason why they are still in jail is because they cannot afford to make bond or bail. The average bail for a case of the survey that we took was $24,000, and the average income of those incarcerated people is $27,000. And so we know that money is the primary factor holding people incarcerated in Louisiana’s jails.

And we also know that African-American people are vastly overrepresented in the incarcerated jail population. African-American people are serving twice as long as their white male counterparts. And we’re also seeing that between the age groups of 15 and 24, that African-American young men are five times as likely to be jailed prior to their trial in Louisiana. And so, this is an extremely problematic situation. Louisiana’s pretrial incarceration population is higher today than it was in 2015, 10% higher. And we, again, lead the world in pretrial incarceration. There is no place in the country that holds more people before trial behind bars than Louisiana.

So we know that we need to see this depopulation effort happen immediately. We’ve seen amazing leadership from Chief Justice Bernette Joshua Johnson, directing law enforcement to stop making nonessential arrests, and asking the criminal district court judges around the state to start releasing people safely, as best they can, with release on their own recognizance, and if not, with a very nominal bail amount. We’ve seen some district judges heed that warning and that directive, and we’ve seen others that have failed to do so. We’ve seen places where they’re not having bail hearings for up to five days or longer. That is unacceptable. It violates our state statutes. It violates the Constitution. It violates speedy trial laws. And we are calling on not just the Supreme Court, which we think has done a fantastic job, but also the governor to start using his executive authority to start releasing people at the jail level, but also at our prison level, which we know the pandemic is really hitting the hardest.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Alanah Odoms of the Louisiana ACLU.

Media Options