Guests

- Rev. James Lawsonacademic, civil rights leader and leading advocate for nonviolence.

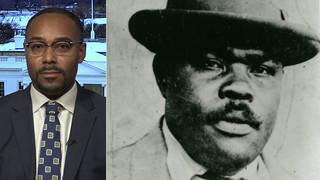

As mourners gathered at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta to honor the life of Georgia Congressmember John Lewis, among those who spoke was civil rights icon Rev. James Lawson, who helped to train John Lewis in nonviolence when Lewis was a student in Nashville. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once described Rev. Lawson as “the leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world.” Lawson invoked John Lewis’s life as a call to action. “We will not be quiet as long as our nation continues to be the most violent culture in the history of humankind,” Lawson said. We feature his extended remarks.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now! The Quarantine Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we bring you highlights from the funeral of Congressmember John Lewis, who died July 17th at the age of 80. Three living U.S. presidents, lawmakers and activists from around the country gathered in Atlanta to honor Lewis, including the Reverend James Lawson, a civil rights icon himself, who helped to train John Lewis in nonviolence when Lewis was a student in Nashville.

Lawson is 91 years old. He helped to form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC, that John Lewis would go on to lead as chairman. In April 1960, Ella Baker invited Lawson to give the keynote speech at SNCC’s founding meeting in Raleigh, North Carolina. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. once described Lawson as “the leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence in the world.” Reverend Lawson addressed mourners gathered at the Ebenezer Baptist Church to remember John Lewis on Thursday.

REV. JAMES LAWSON JR.: I have read many of the so-called civil rights books of the last 50 or 60 years about the period between 1953 and 1973. Most of the books are wrong about John Lewis. Most of the books are wrong about how John got engaged in the Nashville campaign of 1959, ’60. This is the 60th year of the sit-in campaign, which swept into every state of the union, largely manned by students because we recruited students, but put up on the map that the nonviolent struggle begun in Montgomery, Alabama, was not an accident, but, as Martin King Jr. called it, Christian love has power that we have never tapped, and if we use it, we can transform not only our own lives, but we will transform the Earth in which we live.

I count it providential that as I moved to Nashville, Tennessee, dropping out of graduate school, in Nashville came people like Kelly Miller Smith and Andrew White and Johnetta Hayes and Helen Roberts and Delores Wilkerson — and John Lewis — and Diane Nash, C. T. Vivian, Marion Barry, Jim Bevel, Bernard Lafayette, Pauline Knight, Angela Butler. How all of us gathered in 1958 and ’59 and ’60 and ’61 and ’62, in the same city at the same time, I count as being providential. We did not plan it. We were all led there.

And when Kelly Miller Smith and the Nashville Christian Leadership Council met in the fall of 1958, and we determined that if there’s to be a second major campaign that will demonstrate the efficacy of satyagraha, of soul force, of love truth, that we would have to do it in Nashville. And so I planned, as the strategist and organizer, a four-point Gandhian strategic program to create the campaign.

We decided, with great fear and anticipation, we would desegregate downtown Nashville. No group of Black people or other people anywhere in the United States in the 20th century, against the rapaciousness of a segregated system, ever thought about desegregating downtown, tearing down the signs, renovating the waiting rooms, taking the immoral signs off of drinking fountains. But it was Black women who made that decision for us in Nashville. I was scared to death when we made that decision. I knew nothing about how we were going to do this. I had never done it before. But we planned the strategy.

John Lewis did not stumble in on that campaign. Kelly Miller Smith, his teacher at ABC, invited John to join the workshops in the fall of 1959 as we prepared ourselves to face violence and to do direct action and to put on the map the issue that the racism and the segregation of the nation had to end.

And so, on the 60th anniversary of that sit-in campaign, which became the second major campaign of the nonviolent movement of America — those are not my words; John Lewis called what we did between 1953 and 1973 the nonviolent movement of America, not the CRM. I think we need to get the story straight, because words are powerful. History must be written in such a fashion that it lifts up truly the spirit of the John Lewises of the world. And that’s why I’ve chosen just to say a few words about it.

Kelly Miller Smith invited John Lewis. I met a Fisk student who told me about a student from Chicago who wanted to do something about those vicious signs. I said, “Invite Diane Nash to the workshop in September, because we’re going to do something about those signs.” I pushed this hard.

Now, John Lewis had no choice in the matter. You should understand that, because all the stories we’ve heard this morning of John becoming a preacher, preaching to the chickens, and other sorts of things, becoming ordained as a Baptist minister — something else was happening to John in those early years. John saw the malignancy of racism in Troy, Alabama. There formed in him a sensibility that he had to do something about it. He did not know what that was, but he was convinced that he was called, indeed, to do whatever he could do, get in good trouble, but stop the horror that so many folk lived through and in, in this country, in that part of the 20th century.

John was not alone. Martin King had the same experience as a boy. I had the same experience from age 4 in the streets of Massillon, Ohio. Matthew McCollum, a pastor whose name you don’t know, in South Carolina, had the same experience. C. T. Vivian had the same experience. I maintain that many of us had no choice to do, but we tried to do, primarily because at an early age we recognized the wrong under which we were forced to live, and we swore to God that, by God’s grace, we would do whatever God called us to do in order to put on the table of the nation’s agenda this must end. Black lives matter.

And so, between 1953 and 1973, we had major campaigns year after year, thousands of demonstrations across the nation that supported it. We had folk in the Congress, folk in the White House, folks scattered across the United States, who were beginning to formulate what the solutions are for change. The media makes a mistake when John is seen only in relationship to the voting rights bill of '65. However important that is, you must not remember that in the ’60's, Lyndon Johnson and the Congress of the United States passed the most advanced legislation on behalf of we the people of the United States that was ever passed, Head Start, billions of dollars for housing.

We would not be in the struggle we are today in housing if President Reagan hadn’t cut that billions of dollars for housing, where local churches and local nonprofits could build affordable housing in their own communities, being sustained and financed by loans from the federal government. We passed Medicare. We passed anti-poverty programs, civil rights bill ’64, ’65, voting rights bills — a whole array. John Lewis must be understood as one of the leaders of the greatest advance of Congress and the White House on behalf of we the people of the U.S.A.

We do not need bipartisan politics if we’re going to celebrate the life of John Lewis. We need the Constitution to come alive! We hold these truths to be self-evident. We need the Congress and the president to work unfalteringly on behalf of every boy and every girl, so that every baby born on these shores will have access to the tree of life. That’s the only way to honor John Robert Lewis. No other way.

Let all of us in this service today, let all the people of the U.S.A. determine that we will not be quiet as long as any child dies in the first year of life in the United States. We will not be quiet as long as the largest poverty group in our nation are women and children. We will not be quiet as long as our nation continues to be the most violent culture in the history of humankind. We will not be quiet as long as our economy is shaped not by freedom but by plantation capitalism that continues to cause domination and control rather than access and liberty and equality for all.

The forces of spiritual wickedness are strong in our land because of our history. We have not created them. John Lewis did not create them. We inherited them. But it’s our task to see those spiritual forces. I’ve named them racism, sexism, violence, plantation capitalism. Those poisons still dominate far too many of us, in many different ways. John’s life was a singular journey, from birth through the campaigns in the South and through Congress, to get us to see that these forces of wickedness must be resisted. Do not let our own hearts drink any of that poison. Instead, drink the truth of the life force. If we would honor and celebrate John Lewis’s life, let us then recommit our souls, our minds, our hearts, our bodies, our strength to the continuing journey to dismantle the wrong in our midst and to allow a space for the new Earth and new heaven to emerge.

I close with this poem from Langston Hughes, which is a kind of a sign and symbol of what John Lewis represents, and what we, too, can represent in our continuing journey. Langston Hughes:

“I dream a world where no human

No other human will scorn,

Where love will bless the earth

And peace its paths adorn

I dream a dream where all

Will know sweet freedom’s way,

Where greed no longer saps the soul

Nor avarice blights our day.

A world I dream where black and white

And yellow and blue and green and red and brown,

Whatever your race may be,

Will share the bounties of the earth

And every woman and man and boy and girl is free,

Where wretchedness hangs its head

And joy, like a pearl,

Attends the need of all humankind —

Of such a world, I dream!”

Celebrate life, dream and labor, for an Atlanta and Los Angeles and a United States and a world. That is to celebrate the spirit and the heart and the mind and soul of John Lewis, and to walk with him through the galaxies, seeking equality, liberty, justice and the beloved community for all. Thank you.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s civil rights icon Reverend James Lawson, 91 years old, speaking at the funeral of his friend and civil rights ally, Congressmember John Lewis.

When we come back, former President Obama eulogizes John Lewis. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Kathleen Bertrand singing “If I Can Help Somebody” at John Lewis’s funeral Thursday.

Media Options