Guests

- Randall Robinsonfounder and past president of TransAfrica, and an academic, author and activist.

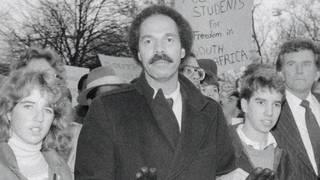

We remember the human rights activist and lawyer Randall Robinson, the founder of TransAfrica, who died Friday at the age of 81. Robinson played a critical role in the anti-apartheid movement in the United States and was a prominent critic of U.S. policy in Haiti. In 2004, he helped expose the U.S. role in the coup that ousted Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. We air excerpts from a 2013 interview Robinson did with Democracy Now! about his work.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, as we end today’s show remembering the human rights leader, lawyer, Randall Robinson, who has died at the age of 81 in St. Kitts, where he had lived since 2001.

Robinson was the founder of the group TransAfrica. He played a key role in the launching of the Free South Africa Movement, arrested many times at the South African Embassy in Washington. He also fasted, went on hunger strike, protesting against the apartheid regime and U.S. involvement with it. He was also a leading advocate for reparations for slavery. Randall Robinson also spoke out for years against U.S. policy in Haiti. In 2004, he helped expose the U.S. role in the coup that ousted Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

Randall Robinson’s books included An Unbroken Agony: Haiti, from Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President, The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks, and Quitting America: The Departure of a Black Man from His Native Land.

In [2012,] Juan González and I interviewed Randall Robinson in our studio. He had just published his book Makeda.

RANDALL ROBINSON: When I was a child growing up in Richmond, Virginia, we were called Negroes. No one I knew knew why we were called that. No one knew the provenance of that word. It had no connection to what we might have been before we were blocked from view by that lethal, opaque space of slavery. And so, we didn’t know anything about ourselves, except we had been called this, but not by ourselves. And it turns out that it’s much like the case of the sardine. There’s no such thing as a sardine as a fish living free in the ocean. It only becomes one when it is captured and put in a can. And we were only called Negroes when we were labeled during slavery as that as a way of severing us from any memory of what we had been. And so we lost our mothers, our fathers, our families, our religions, our languages, our cultures, our memories of what we had been. And so, we thought we had no history before slavery. And this name, this new name, this new label, helped to facilitate that loss of memory. Now, memory is the active agent of all collective social progress. If you can’t remember yourself, you’re suffering from serious debilitation.

This novel is the story of an extraordinary woman who is a poor, blind waitress in Richmond, Virginia, who remembers past lives. And so, she remembers Timbuktu in the late 1300s, when her father was a priest who underwent cataract surgery at the University at Timbuktu. She remembers her days in ancient Egypt, when the two Egypts were united thousands of years before. She remembers lives in West Africa. She remembers all of this, and she tells it to her grandson, who wants to be a writer. And they have a special relationship. And she swears him to secrecy that he tell no one that she has these memories, or people will think she’s a bit fruity, as she says. But she remembers these lives in extraordinary detail. And he is inspired by it. He gains his confidence from it. And this is, of course, to symbolize the enormous consequence. Sometimes when we think of slavery, we calculate the economic consequence of it. But we have not calculated the psychosocial consequence of it, unless we factor in the loss of memory, which was occasioned by a deliberate and systematic program imposed from those — by those who controlled us.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: When you were at TransAfrica and were working in Washington, the climate in Washington in the ’80s and ’90s was just more incarceration, more incarceration. Did any of the political leaders that you dealt with realize the long-term impact of what was happening?

RANDALL ROBINSON: I recall that when we were first being arrested at the embassy and I went to jail that first night, everyone in the lock-up with me was Black.

AMY GOODMAN: This was — you were being arrested for protesting apartheid South Africa.

RANDALL ROBINSON: For protesting at the embassy. Everyone was Black. And I had some sense of this. I think at the time I was told that one out of every three young Black males in the District of Columbia was under one or another arm of the criminal justice system. And what stunned me about it, and what continues to bother me about it, is that when we were struggling during the civil rights movement, some of us were in better positions to benefit from this change that was coming than others were. And so, while we had all been in the same boat during segregation, when change came, we weren’t all in the same boat anymore. Some of us could escape, but others of us were bottom-stuck. And I don’t believe that those of us who escaped worked as hard, as tenaciously, since, to remember those of us who could not.

And the result is that we now see our future as a people in America being warehoused. How can we not be concerned, in some relentless way, about the fate of all of these young Black people who are being imprisoned? Because we are indissolubly bound up with them. Their future is our future. Our future is their future. And we have to be mindful of that. But it doesn’t so much penetrate if we don’t have news of it every day. So many people don’t know.

AMY GOODMAN: Randall Robinson, talking about movements, you spearheaded the anti-apartheid movement in this country, getting arrested numerous times, among other places, in front of the South African Embassy. You fasted almost unto the death to stop the — to fight the U.S. government — President Clinton, I think, at the time — to allow Haitians to come into this country at the time of the bloody coup of 1991 to 1994 in Haiti. Talk about the power of movements and what you see, from your perspective now living in St. Kitts, having quit America — the name of one of your books — what you think needs to happen in this country.

RANDALL ROBINSON: Just 12% of the people who commit nonviolent drug infractions are Black, I think 56% of those, nonetheless, who are prosecuted, and something on the order of 75% of those who are imprisoned. I mean, we can see the striking unfairness of it. But we have to find a way to get that information to people. Outrage has to be informed by information to go anywhere. South Africa worked because everybody knew about the apartheid system when we went to jail. And so, it was instant. This is a little bit more difficult.

We’re backward in the world in so many ways. We find ourselves in bed with China, Iran and two or three other nations in our embrace of the death penalty, when the rest of the world is moving in the other direction. But 75% of those executed are Black and Hispanic. And so, the unfairness of it is seen in the statistics of who pays and who doesn’t. We get sentences twice as long for commission of the same crime. It’s just fundamentally unfair.

And the question, Amy, is how we can put this together in a way that is consumable and inspiring to people to let them know that this is not just a Black or racial issue, it’s an issue for all Americans who care about democracy and equity and fair play and decency. And that’s what we have to do. We are killing our own country’s future, is what we are doing. And we’re killing genius in jail cells that does not have a chance to blossom and to flower.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Randall Robinson in [ 2012 ] in an interview Juan González and I did with him and Michelle Alexander. You can see the whole interview at democracynow.org. We’ll also link to his interview in 2007 on Haiti.

Randall Robinson just died this weekend at the age of 81 in St. Kitts, where he had lived since 2001. He was the founder of the group TransAfrica, played a key role in the launching of the Free South Africa Movement. He was arrested many times at the South African Embassy in Washington, D.C., protesting against the apartheid regime. His books included The Debt: What America Owes to Blacks and Quitting America: The Departure of a Black Man from His Native Land, as well as the book An Unbroken Agony: Haiti, from Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President. To see all of our interviews, go to democracynow.org, with Randall Robinson.

Democracy Now!'s Juan González is moderating an online panel today on “Chicago's 2023 Mayoral Race: Reclaiming Harold Washington’s Multiracial Coalition.” You can see details at democracynow.org.

Democracy Now! is also currently accepting applications for a digital fellow. You can learn more and apply at democracynow.org.

Democracy Now! is produced with Renée Feltz, Mike Burke, Deena Guzder, Messiah Rhodes, Nermeen Shaikh, María Taracena, Tami Woronoff, Charina Nadura, Sam Alcoff, Tey-Marie Astudillo, John Hamilton, Robby Karran, Hany Massoud and Sonyi Lopez. Our executive director is Julie Crosby. Special thanks to Becca Staley, Jon Randolph, Paul Powell, Mike Di Filippo, Miguel Nogueira, Hugh Gran, Denis Moynihan, David Prude and Dennis McCormick. To see all of our interview segments, you can go to democracynow.org. I’m Amy Goodman.

Media Options