Topics

Guests

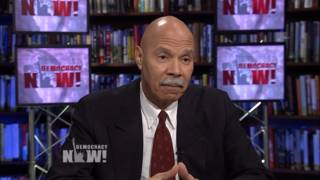

- Randall Robinsonfounder and past president of TransAfrica, and an academic, author and activist.

We continue to remember the lawyer and human rights activist Randall Robinson, the founder of the racial justice group TransAfrica, who died last week at age 81. Robinson was a leader in the U.S. movement against South African apartheid and was a prominent critic of U.S. policy in Haiti, including the U.S.-backed coup against President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 2004. Democracy Now! spoke to Robinson in 2007 about that episode and how foreign powers have interfered in Haiti throughout the country’s history, beginning with the slave revolt against France that established Haiti as the first free republic in the Americas in 1804. “The Haitians believed that anybody who was enslaved anywhere had a home and a refuge in Haiti. Anybody seeking freedom had a sympathetic ear in Haiti. But because of that, the United States and France and the other Western governments, even the Vatican, made them pay for so terribly long,” said Robinson, who had just published the book An Unbroken Agony: Haiti, from Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

We end today’s show continuing our look at the life and legacy of the human rights leader Randall Robinson. He died Friday at the age of 81 in St. Kitts, where he’s lived since 2001. Randall Robinson was the founder of TransAfrica, played a key role in the launching of the Free South Africa Movement, arrested many times at the South African Embassy, and pushed successfully for the imposition of U.S. sanctions against apartheid South Africa.

Randall Robinson also spoke out for years against U.S. policy in Haiti. In 2004, he helped expose the U.S. role in the coup that ousted Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who was flown against his will to the Central African Republic. Two weeks after the coup, Aristide defied the United States and flew back to the Caribbean, flying in to Jamaica. Randall Robinson accompanied Aristide, flew to the Central African Republic, along with Congressmember Maxine Waters and others, picked up President Aristide and his wife Mildred Aristide, and flew back to the Western Hemisphere. I reported on that flight, joining them on that flight, and interviewed Randall Robinson about the U.S. role in the coup.

RANDALL ROBINSON: Condoleezza Rice, Colin Powell and Donald Rumsfeld should be ashamed of themselves. President Aristide is the democratically elected president, the last time by 92% majority, of Haiti. And he has come home to the Caribbean, where he belongs. He is the president, democratically elected, of the democracy that they overthrew. America ought to be ashamed of itself. And we are proud of the role we’ve played in bringing him home to his region, where he belongs and where we hope he will stay.

AMY GOODMAN: Randall Robinson later wrote about the U.S.-backed coup in his book, An Unbroken Agony: Haiti, from Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President. In 2007, I interviewed Randall Robinson again. He described the day Aristide was ousted.

RANDALL ROBINSON: Later that morning, about 30 American Special Forces troops in full combat gear, in 12 or 13 white Chevy Suburbans of the American Embassy, surrounded the Aristide home, took positions on the wall around the home. And you could see the red tracer pattern crisscrossing, crosshatching in the yard of the home. And into the yard came one Chevy Suburban with one of the Special Forces people fully armed, who was attending Luis Moreno of the American Embassy, who walked into the house and told the president, “I was here when you came back in '94, and I'm here tonight to tell you it’s time for you to leave.”

They removed the president — Moreno and the American Special Forces — from his home, took them to the airport — the president, Mrs. Aristide and Frantz Gabriel — took them from their home, boarded them on this large wide-bodied aircraft with no markings, no tail number, only the sort of large flag, American flag, on the vertical tail assembly, and flew off, making their first refueling stop in the eastern Caribbean in Antigua.

AMY GOODMAN: Our guest for the hour, Randall Robinson, just up from St. Kitts, where he has been living for the last six years. He has just published a new book called An Unbroken Agony: Haiti, from Revolution to the Kidnapping of a President.

Let’s talk history for a minute, something the U.S. press doesn’t give us very much of. To understand the U.S. role today in Haiti, can you go back in time to how Haiti was founded in 1804?

RANDALL ROBINSON: Well, Haiti was the largest piece of France’s global empire. It was its great profit center, that slave colony with 465,000 enslaved Africans working there, many of whom had been soldiers in African armies before they were brought to Haiti. And in August of 1789 — or 1791, rather, 40,000 of those slaves revolted and started a war that lasted 12-and-a-half years under the leadership of an ex-slave and a military genius named Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines. And this army of ex-slaves defeated two French armies, first the French army before the completion of their revolution and then another army dispatched by Napoleon under the leadership of his brother-in-law, and then the armies of England and Spain. A hundred and fifty thousand Blacks died in that 12-and-a-half-year war. And in January of 19 — of 1804, rather, they declared Haiti the first free republic in the Americas, because the United States was then a country that held slaves.

During the revolution, Thomas Jefferson said he would like to reduce Toussaint to starvation. George Washington lamented and vilified that revolution. The U.S. imposed an embargo, recognized a new French government, but did not recognize the new Haitian free government and imposed a comprehensive economic embargo on Haiti until the Emancipation Proclamation. In fact, France imposed reparations on Haiti in 1825, and the interest that Haiti had to pay in loans that were American and French loans to service this debt to France, absorbed virtually 80% of Haiti’s available budget 111 years after the completion of their revolution until 1915. It was only in 1947 that Haiti was able to pay off its debt.

AMY GOODMAN: The debt that was incurred as a result of France not having access to the enslaved people of Haiti.

RANDALL ROBINSON: The Haitians had to pay France for no longer having the privilege of owning Haitian slaves. That revolution provoked the end of slavery in the Americas. And so, that’s why it is so important that all African people, people generally in the Americas, because Haiti funded and fought in South American revolutions. That’s why Haiti is so honored in places like Venezuela by people like Simón Bolívar. Haiti was central to all of this. And we’re in Haiti’s debt. But it is for that —

AMY GOODMAN: Simón Bolívar came to Haiti.

RANDALL ROBINSON: Haiti, and was given arms and was given men, was given a printing press, because the Haitians believed that anybody who was enslaved anywhere had a home and a refuge in Haiti. Anybody seeking freedom had a sympathetic ear in Haiti. But because of that, the United States and France and the other Western governments, even the Vatican, made them pay for so terribly long. It’s as if the anger of it never abated. I mean, you can hear Frederick Douglass talking about it in the late 1800s, about this thing in the American craw.

AMY GOODMAN: The U.S. government didn’t recognize Haiti for decades, the Congress, going back to Thomas Jefferson, afraid that the slave uprising would inspire U.S. slaves.

RANDALL ROBINSON: Would inspire U.S. slaves to revolt against him in Virginia, and George Washington, and on and on and on. And so, they opposed everything that was being done in Haiti that won their freedom.

AMY GOODMAN: The U.S. government invaded Haiti in 1915 under Wilson.

RANDALL ROBINSON: And Woodrow Wilson invaded Haiti in 1915. And when a Haitian, Péralte, Charlemagne Péralte, organized the Cacos soldiers, these farmers, to fight against this American occupation, the Americans killed him and nailed him to a cross, crucifixion-style, and stood him up, his corpse, in a public place in Haiti to demonstrate to Haitians what would be the price of any defense against the American invasion. The U.S. has played a terrible role in Haiti.

AMY GOODMAN: So, even as the U.S. and France were at loggerheads after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, because France opposed the invasion — that was 2003 — in 2004, they were working together —

RANDALL ROBINSON: Working very much together.

AMY GOODMAN: — in pushing out, forcing out Aristide and bringing him to the Central African Republic.

RANDALL ROBINSON: As a matter of fact, in 2003, late 2003, Aristide organized a reparations conference, and the result of which was a request to France that it repair Haiti by repaying Haiti the $21 billion in current money that Haiti had paid in reparations unjustly to France. Dominique de Villepin responded by sending his sister.

AMY GOODMAN: The foreign minister of France.

RANDALL ROBINSON: The foreign minister of France sending his sister to Haiti to tell Aristide that it was time for him to leave. And that’s how we have — the Western world, France and particularly the United States — have meddled in Haitian affairs. After the abduction of the president, Bush spoke with Chirac on the phone, congratulating each other about how smoothly the abduction of the president had been carried off by both countries.

AMY GOODMAN: Randall, you talked about how when President Aristide was president, before he was forced out, he was supposed to be getting hundreds of millions of dollars from the Inter-American Development Bank, I think it was, for health issues.

RANDALL ROBINSON: The loan had been fully approved. It was for $146 million. It was for health issues, for literacy, for things associated with social programs, roads and some infrastructure projects. The United States blocked that loan. And so, on the one hand, it starved the economy of Haiti. On the other hand, it trained the opposition. On another hand, it armed the paramilitaries. And in the last analysis, American forces invaded and abducted the president.

AMY GOODMAN: The U.S. role, how well known is it in Haiti by Haitians?

RANDALL ROBINSON: Oh, I think it’s very well known in Haiti by Haitians. If it were so well known by Americans, our democracy would work better. The problem is with our democracy. It wasn’t ever with theirs. The problem is what our undemocratic or the behavior, undemocratic behavior, of our government means for struggling democracies across the world, that we feel that we, by divine right, can go in and overthrow governments willy-nilly, when they are living under leadership of their own clear choice. It’s a shameful chapter for Americans and particularly for this administration.

AMY GOODMAN: Human rights advocate and attorney Randall Robinson, speaking in 2007. He died Friday at the age of 81 in St. Kitts. To see Democracy Now!'s exclusive coverage of Randall Robinson and Congressmember Maxine Waters and others' trip to the Central South African Republic to pick up the Aristides after they were ousted in a coup, go to democracynow.org, as well as all of our interviews. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

Media Options