After thousands gathered Saturday in Washington, D.C., to mark the 60th anniversary of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s historic “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington, we speak with Gary Younge, author of The Speech: The Story Behind Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s Dream. “There is this notion of King’s dream speech as being folded into America’s liberal mythology: America is always getting better, it’s always getting more wonderful,” says Younge, who wrote his book on the speech to reflect America’s current struggle with white supremacy and attacks on people of color. “As things can go forwards, so can they go backwards.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: So, let’s be very clear about that March on Washington. In fact, it was on August 28th, 1963, which was observing the anniversary of the death of Emmett Till — right? — a 14-year-old boy who was killed, lynched by whites, taken from his uncle’s home in the middle of the night in Money, Mississippi.

GARY YOUNGE: That’s right that it took place honoring that anniversary and evoking a range of violent acts that had taken place throughout the decade or so prior, but that had also seen a huge swelling of resistance that said, you know, not that African Americans ever just accepted their lot, but the organization and the level of resistance had been ramped up in that decade or so since Till’s murder, and that, in some ways, the March on Washington was a symbolic kind of crescendo to that period of resistance.

AMY GOODMAN: So, I want to go from Jacksonville to this 60th anniversary of the '63 March on Washington. People often don't realize its official title was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. These were the words of the Reverend Martin Luther King 60 years ago today.

REV. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.: I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” I have a dream that one day on the Red Hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

AMY GOODMAN: That was Reverend Martin Luther King 60 years ago today. Well, on Saturday, thousands gathered in Washington, D.C., to mark this 60th anniversary. Organizers included the Reverend Al Sharpton of the National Action Network.

REV. AL SHARPTON: Sixty years ago, Martin Luther King talked about a dream. Sixty years later, we’re the dreamers. The problem is we’re facing the schemers. It’s the dreamers on one side, the schemers on the other. The dreamers are fighting for voting rights; the schemers are changing voter regulations in states. The dreamers are standing up for women’s right to choose; the schemers are arguing whether they’re going to make you stop at six weeks or 15 weeks. The dreamers are saying that if you’re LGBTQ or trans, you have a right to your life; the schemers are saying, “We’re going to make you look like you’re something that should not be tolerated in human society.” It’s the dreamers against the schemers. The dreamers are in Washington, D.C.; the schemers are being booked in Atlanta, Georgia, in the Fulton County Jail. The dreamers will win. The dreamers will march. The dreamers will stand up, Black, white, Jewish, LGBTQ. We are the dreamers. We’re the children of the dream.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Al Sharpton on the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington. But let’s go back to the original 1963 march and that famous speech, the one you, Gary Younge, wrote a book about, The Speech: The Story Behind Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Dream. We chose that clip of the dream, because, in fact, it wasn’t going to be in the speech. Is that right? Talk about his close ally, the person who was with him the night before — he was with a group of his allies talking about what he should say — the Reverend Wyatt Walker.

GARY YOUNGE: Well, that’s right. The Reverend Wyatt Walker said to King, because the dream sequence had been used in several speeches previously, most — best heard, I think, in Detroit not long before, and Wyatt Walker said to him, “Don’t use the dream bit. You know, you’ve done it over and over again. It’s hackneyed. It’s tired. Do something new.” And one thing —

AMY GOODMAN: And let’s talk about this, Gary, that — I mean, you write about this so eloquently in The Speech. He had just talked about it at a — addressing the — what? Insurance Association of America and, before that, a few weeks before, Detroit.

GARY YOUNGE: That’s right, so, I think, before insurers in Chicago. And, I mean, King had given a lot of speeches during that time, but you have to remember lots of people didn’t have television, and so this was his chance to speak both to America and to the world. Unless you were in the movement or you’re African American and active in the church, you maybe probably hadn’t heard him speak. So this was his chance. And he was worried that he was going to sound too hackneyed, too trite. That’s what Wyatt Walker said: It’s trite.

And so, if you listen to the speech, he is actually winding down. As he used to say, when he was speaking, it was like looking for a place to land, like he was a pilot looking for a place to land. And you can hear him saying, “Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama.” He’s looking for a place to land. And it’s Mahalia Jackson, whose voice we heard right at the beginning, who was at the Detroit march, who says, “Tell them about the dream, Martin. Tell about the dream.” And Clarence Jones, who had written the first draft of the — the draft that was printed of the speech but doesn’t have the dream in it, he [inaudible] that he saw King, in his body, shift from a politician to a preacher. And he turned to the person next to him and said, “These people don’t know, but they’re about to go to church.” And then King starts on his dream sequence, which becomes the thing that is best known about what is called the dream speech for a reason.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Gary Younge, let’s talk about another addition that he was warned, “No, you’ve said this before. Don’t say it again.” I want to play the clip of Dr. King talking about the bad check.

REV. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.: In a sense, we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men — yes, Black men as well as white men — would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Martin Luther King, 60 years ago today. Talk about the bad check and how it made it into this speech, Gary.

GARY YOUNGE: Well, he was very keen that there was some kind of analogy or description that would span, in a way, from slavery through to the '60s and make it clear, in as accessible a way as possible, that, short of talking about reparations, which wouldn't have really worked in that kind of venue, that America owes us, and it owes us morally, but it also owes us also materially. There were some who were not keen on that kind of — that analogy. They thought it went too far. They thought it was too crude.

But, actually, in some ways, I think it’s the most — it’s not the most florid piece of the speech, but it’s, in some ways, the most important, because it speaks to now, that the check keeps bouncing. And, in fact, in a way, things are going backwards. The account is getting worse, if you look at them rolling back the voting rights and affirmative action and so on.

And one has to think — and some of the people that I spoke to for the book said this — how people would understand this differently if it was understood as the bad check speech, as the promissory note speech, how that might shift their understanding, because actually what happens with this speech is that all sorts of people, awful people and good people, but the awful will take a moment from this speech and claim it, including Ron DeSantis did his anti-woke bill. He evoked Martin Luther King and that one line about his children being judged by the content of their character, not the color of their skin. That’s the only line that right-wingers and Republicans know. And actually, even Ron DeSantis, even when talking about banning books that would really refer to the roots of this struggle, evokes Martin Luther King, which is why I thought it was so important to write the book, because I felt that he and this speech had to be reclaimed and positioned in its kind of rightful space, and I wanted to make a contribution to that.

AMY GOODMAN: And in talking about the bad check, the issue of the insufficient funds, it reinforces the name of the speech, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, not just for freedom, talking about the economic plight of a population that had been formerly enslaved. If you can also talk about what is most misunderstood about August 28th, 1963, about this gathering, where, early in the morning, reporters were on radio and television saying, “It looks like not that many people are going to come out.” You have the amazing organizers of this speech, A. Philip Randolph. You have Bayard Rustin. Rustin, you write about, taking out his watch and a blank piece of paper, when reporters are saying, “It doesn’t look like you’re going to have anyone coming to the speech,” and he said, “No” — and the paper was blank — what did he say? “We’re right on schedule.”

GARY YOUNGE: “We’re right on schedule,” yeah. I mean, first of all, we have to understand that a march of this size had actually never been organized before in the capital, that the state assumed that there would be violence, and militarized the capital to a huge extent. And in the end, there was no violence.

That, as you have pointed out, it was a march of jobs and freedom, organized jointly, civil rights movement and the labor movement, class and race, an implicit, I think, understanding that to try and understand racism without class, or class oppression without race, is to really misunderstand both completely. So that makes it a march, as you said, for jobs and freedom.

This force of energy that is Bayard Rustin, this gay African American man who stands at the heart of the organizational excellence, really, in getting everybody into the city and out of the city, to the extent that the minutiae went to telling people, “Don’t bring egg mayonnaise sandwiches. It’s going to be a hot day. The mayonnaise will go off. It will get you sick. There are only so many toilets.” That is the extent of the kind of the organization that there was.

A fragile coalition, which included some of the more conservative elements, and the unions were among some of the more conservative elements in some ways, and SNCC, and the sprightly, frightly John Lewis, the late John Lewis, whose speech was the subject of frantic last-minute negotiations, because he wanted to talk about the protesters marching through the South as Sherman did at —

AMY GOODMAN: You know, Gary, we’ve got a clip of John Lewis speaking at the march. He was the youngest speaker. He was 23 years old. This is John Lewis.

JOHN LEWIS: To those who have said, “Be patient and wait,” we must say that we cannot be patient. We do not want our freedom gradually, but we want to be free now. We are tired. We are tired of being beaten by policemen. We are tired of seeing our people locked up in jail over and over again, and then you holler, “Be patient.” How long can we be patient? We want our freedom, and we want it now.

AMY GOODMAN: “We want our freedom, and we want it now,” John Lewis said at the age of 23, a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, known as SNCC. He originally wrote, for the speech, as you were talking, Gary, about these frantic negotiations forcing him to rewrite his speech — he originally wrote, “We cannot depend on any political party, for both the Democrats and the Republicans have betrayed the basic principles of the Declaration of independence. … We will march through the South, through the Heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own 'scorched earth' policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground nonviolently.” Take it from there, Gary.

GARY YOUNGE: Well, you see the energy of what will soon become the Black Power movement. You see the negotiations with a more religious and older generation and the union movement. In the end, it’s A. Philip Randolph who says, “I’ve been waiting for this moment,” because A. Philip Randolph sought to organize a march on Washington, I think, in 1943, certainly during the war. It may have been '42. But it was in order to ensure that Black people could work in the munitions factories. And he only called it off when Roosevelt relented and issued an executive order. And he said to John Lewis, “Young man, I've been waiting for this time to come all of my life. Please, please, do this for me.” And Lewis relents.

But then, also, that energy from Lewis also kind of tells a story about what happened during that year, because at the beginning of that year, only Randolph and Rustin really wanted a march. The NAACP, the Urban League, all of those, they didn’t really want anything to do with it. And actually, SNCC, the SNCC crowd, thought it would be like a big show, a march in Washington, whereas they wanted to march on Washington. And it’s really the events in Birmingham, Alabama, earlier in the year which forced the leadership — this comes from the grassroots — it forces the leadership to say, “Well, now we have to have a march. We have to do something.” And the story of that year is the leaders literally — well, figuratively running to catch up with the base, which, on the day, they literally do, because they’re in — they go to meet Congress, the people in Congress, and the march starts without them, and they have to kind of run to catch up. And the picture that there is which looks like they’re leading the march, actually, they’re near the front, but they’re not at the front. They just cleared people to make it look as though it was.

And there’s an interesting moment where King and Randolph and others, James Foreman from CORE, they are in — speaking to Kennedy just a week or so before the march, and Kennedy is trying to get them to call it off. And Randolph says — he says, “We want legislation on the Hill, not a big show, not Negroes in the streets.” And Randolph says, “The Negroes are already on the streets, Mr. President, and I doubt if we called them that they would get off.” And that gives you a really clear, clear indication of who was really driving this and what was really driving this.

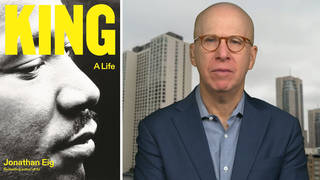

AMY GOODMAN: Gary Younge, we want to thank you so much for being with us, professor of sociology at the University of Manchester, currently in Italy. He’s the author of several books, including The Speech: The Story Behind Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Dream, which has just been updated with a new prologue for this 60th anniversary of that historic day in Washington. Gary Younge’s forthcoming book is Dispatches from the Diaspora: From Nelson Mandela to Black Lives Matter.

Coming up, the city of White Plains, New York, has agreed to a $5 million settlement with the family of Kenneth Chamberlain, the Black 68-year-old former Marine shot dead by police in his own apartment after he accidentally triggered his medical alert pendant and they came for a wellness check. Back in 30 seconds.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: “Oh, Freedom,” performed by Odetta. She performed “Oh, Freedom” 60 years ago at the March on Washington.

Media Options