Guests

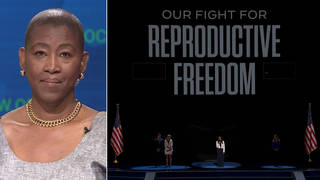

- Michele Goodwinprofessor of constitutional law and global health policy at Georgetown University and founding director of the Center for Biotechnology and Global Health Policy.

The Supreme Court has unanimously rejected a challenge from anti-abortion groups to the nationwide availability of the abortion medication mifepristone, which is available by mail and can be taken at home in many states. However, advocates warn the far-right-dominated court’s ruling on the FDA’s authority to regulate the pill was purely on procedural grounds, and could even offer a “roadmap” for future challenges. Mifepristone is used in roughly two-thirds of all U.S. abortions, including in some states that have severely limited or banned abortions. “This is just one of the strikes — not the first strike, not the second or third, but one of the strikes — in an artillery that is aimed at reproductive freedom,” says our guest, legal scholar Michele Goodwin. We discuss the ruling and the anti-abortion movement’s “playbook” of attacks on reproductive healthcare with Goodwin.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: In a closely watched case Thursday, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled to preserve access to the abortion pill mifepristone, which is used in roughly two-thirds of all U.S. abortions. The court did not address the safety of the pill and focused instead on the lack of standing by the anti-choice medical associations who filed the lawsuit in order to limit access to the drug approved more than 20 years ago by the Food and Drug Administration.

Advocates warn the court’s ruling could offer a “roadmap” for future challenges. Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote the majority opinion. He said, quote, “The plaintiffs have sincere legal, moral, ideological, and policy objections,” unquote, suggesting the proper venue for their case could be with the president, lawmakers or federal regulators.

Vice President Kamala Harris spoke from the White House after the ruling.

VICE PRESIDENT KAMALA HARRIS: This is not a cause for celebration, because the reality is certain things are still not going to change. We are looking at the fact that two-thirds of women of reproductive age in America live in a state with a Trump abortion ban. This ruling is not going to change that. This ruling is not going to change the fact that Trump’s allies have a plan, that if all else fails, to eliminate medication abortion through executive action.

AMY GOODMAN: The Supreme Court will soon rule in another case that aims to strip pregnant people of their right to abortion care in order to stabilize an emergency medical condition. Meanwhile, Senate Republicans blocked a bill Thursday to protect access to in vitro fertilization and voted last week against the Right to Contraception Act.

For more, we’re joined by Michele Goodwin, professor of constitutional law and global health policy at Georgetown University, founding director of the Center for Biotechnology and Global Health Policy. She hosts the Ms. magazine podcast On the Issues with Michele Goodwin and is the author of Policing the Womb: Invisible Women and the Criminalization of Motherhood. In 2021, her guest essay for The New York Times was headlined “I Was Raped by My Father. An Abortion Saved My Life.”

Professor Goodwin, welcome back to Democracy Now! Can you respond to the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision, what it means and what it doesn’t mean?

MICHELE GOODWIN: What it means is that mifepristone, which is used as part of a two-drug regimen in order to terminate pregnancy — the majority of pregnancy terminations, abortions, in the country take place with mifepristone. What this means is that it continues to be available nationwide. It means that people may not be criminally punished for using this to help a patient terminate a pregnancy. But, as the vice president said, it should not be overstated what this ruling means. This was a ruling on procedural grounds, not substantive grounds.

And it’s worth noting how far this group of litigants got. They framed themselves as doctors who would be affected by patients who had some distress, medical distress, after abortion. That itself was something of a tremendous falsehood. Mifepristone is safer than using aspirin and Tylenol. The Supreme Court has acknowledged, in 2016, that a woman is 14 times more likely to die carrying a pregnancy to term than by having an abortion. So, the underlying premise that the drug is unsafe, that abortions are unsafe, was factually not true. It was also an incredible reach that somehow — this claim that the FDA had rushed this drug to the marketplace, when, in the year that it was approved, the FDA had spent three times the length of time reviewing this drug compared to other drugs that came into the marketplace that year. So, the drug was efficacious, and the drug was safe. And yet these plaintiffs were able to get as far as the Supreme Court in bringing this case. And that says so much.

AMY GOODMAN: What role does telemedicine play in providing access to abortion pills? And how will it be affected?

MICHELE GOODWIN: Well, what this also means is that telemedicine can continue to be used in order to help people be able to terminate a pregnancy.

Part of the challenge to this case by these people who brought it — and this is also important, Amy — these are people who claim to be doctors. Amongst them was a person who has a master’s degree in theology, who would never get medical admitting privileges at any hospital; another one, a dentist, who’s not a person that one would seek to have help in a gynecological ward. But that said, they claim to be doctors who would be put in a difficult position helping someone to be relieved after complications with an abortion.

What this case does do with telemedicine is that it keeps it alive. And it’s important to understand the playbook behind all of this. Part of the playbook is to find any kinds of opportunities, holes, etc., and to pierce them, to try to use the United States Supreme Court, district courts, courts of appeals in any kind of way to further limit and diminish the ability to be able to access reproductive freedom. And so, it’s not even just about abortion. You’ll find that this case and others like it are open doors to also diminishing the right to access contraception, the ability to be able to get things in the mail that help you with your reproductive health. This is just one of the strikes — not the first strike, not the second or third, but one of the strikes — in an artillery that is aimed at reproductive freedom.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you explain judge shopping, who the Trump-appointed Judge Matthew Kaczmarek is in Amarillo, Texas, and what he has to do with this case?

MICHELE GOODWIN: This is a great question, because what’s come open in the wake of so many of the appointments that the former president was able to make, Donald Trump was able to nominate and get through the confirmation process more federal judges than any other president, save George Washington. And many of the people that were part of that nomination process were people who showed a coolness towards cases like Brown v. Board of Education, Roe v. Wade, etc.

So, Judge Kaczmarek is one of them. He was an activist — is an activist, an anti-abortion activist. He has written about his anti-abortion views. He has been quite outspoken about his anti-abortion views, save for a publication that he had sort of — he had his name removed from when he was going through the confirmation process, which was going to be published by a Texas — University of Texas law review. He had his name taken off of that. But it was an article that was about abortion and his opposition. So, this group of litigants brought their case before Judge Kaczmarek, who’s the only sitting judge in Amarillo, Texas, a person with known anti-abortion views. And what they had hoped to do was to play off of his anti-abortion views by bringing this case before him.

Now, what this also says is a lot about how the U.S. judiciary has been functioning in recent years. There’s supposed to be objectivity, arm’s-length distancing, such that if one has personal views that may be oppositional in matters of race and sex and LGBTQ equality, that is not supposed to infect the process of judging. Many have said that that’s exactly what happened in this case, that there was an infection that was here with Judge Matthew Kaczmarek, that he allowed his personal views, which have been widely expressed, to influence how he handled this case, including on the matter of standing. The fact that the United States Supreme Court unanimously threw out this case saying that these plaintiffs have no standing, it should not have gotten that far. And Judge Kaczmarek was the one who opened the door to it.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Goodwin, what does the next move of anti-abortion crusaders look like, based on this Supreme Court result? And if you can talk about EMTALA and what it means?

MICHELE GOODWIN: Yes. Well, the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act says it all — doesn’t it? — in its name. When Congress enacted this law, it was intended to protect all Americans, and quite specifically women who would be in distress during pregnancy. At the time in which this federal law was passed, there were poor pregnant women who were literally, Amy, being dumped on the side of roads. These were women who had no health insurance. Of course, there’s not universal healthcare in the United States. Since EMTALA’s enactment, there’s been the federal protections of healthcare, the Obamacare, but it’s not universal healthcare. But at the time, women were being dumped on the side of roads. Poor women were showing up at American hospitals in labor, sometimes in very stressful conditions, women who needed miscarriage being managed, and they were literally being turned away because they didn’t have insurance, or the right insurance. Because of deaths and tragedies that were associated with this, Congress passed this law, the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, otherwise known as EMTALA, that grants all Americans the privilege, the right, to be stabilized when they are in a healthcare crisis. You can imagine what this might mean if someone is suffering a heart attack, a stroke, needing to manage a miscarriage, going to a hospital, and the hospital saying, “Sorry, we can’t stabilize you. We can’t treat you.”

Well, there’s another case that is being seen by the court, that the court will be ruling on soon, that involves Idaho’s challenge to EMTALA’s application to women who need their pregnancies managed, their miscarriages managed. Idaho claims that EMTALA should not apply to the state. This raises very serious questions in American constitutionalism, American rule of law, because federal law always supersedes and trumps states’ laws. But in the wake of the anti-abortion movement and the forcefulness of it, you hear these kinds of claims coming from governors and states’ attorneys general that federal law doesn’t matter; federal law cannot supersede or trump what the state is seeking to do, specifically on matters of reproductive health. We saw that before the Dobbs decision when the state of Texas passed its S.B. 8 law, which banned abortion after six weeks of pregnancy. That was a showdown against Roe v. Wade that the United States Supreme Court turned a blind eye to and let stand. Well, now Idaho is doing the same. We’ll see how the Supreme Court comes out on this.

But let me also say this, Amy. This issue of the Comstock Act, this Comstock law, dating back to 1873, it’s another weapon in the arsenal of the anti-abortion movement. This is a playbook, turning to the playbooks of times in which slavery existed or just after slavery, a time in which women couldn’t vote, had very limited representation within law at all, times in which marital rape was permissible, marital domestic violence permissible. So, part of the anti-abortion movement is to look back at a time in which women barely had citizenship, by law, in the United States, and to pull from that past in order to inform the present and the future.

AMY GOODMAN: Michele Goodwin, I want to thank you so much for being with us, professor of constitutional law and global health policy at Georgetown University, founding director of the Center for Biotechnology and Global Health Policy, author of Policing the Womb: Invisible Women and the Criminalization of Motherhood.

Coming up, New York City’s chapter of the Audubon Society changes its name. Why? John Audubon, the founding father of American birding, was a slaveholder. Today we mark Pride Month with the rest of the show, speaking to Christian Cooper, Black birder and LGBTQ activist, made headlines four years ago when a white woman in Central Park called 911, claiming he was threatening her life after he asked her to leash her dog. Back in 30 seconds.

Media Options