We discuss the plea deal and release of Julian Assange with Australian journalist Antony Loewenstein, and the reaction in Assange’s home country of Australia to his release and WikiLeaks’s legacy, which he says helped open the door to whistleblowers and leakers in the era of digital journalism. Loewenstein, the author of The Palestine Laboratory, also discusses the state of press freedom in Israel’s war on Gaza. The Israeli military doesn’t view Palestinian journalists as journalists, he argues. Instead, it views them as “akin to terrorists” to justify its targeting of them, an issue that Loewenstein argues should be of more concern to Western media outlets.

More from this Interview

- Part 1: Julian Assange Is Free: WikiLeaks Founder’s Brother Gabriel Shipton on End of Decadelong Legal Saga

- Part 2: Press Freedom Advocates Celebrate Julian Assange’s Release, But Warn of Impact of Plea Deal

- Part 3: Journalist Antony Loewenstein on Assange’s Release, WikiLeaks & Israeli Drones Killing Gaza Reporters

Transcript

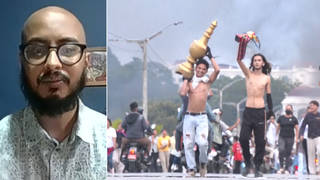

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to bring Antony Loewenstein into this conversation, independent journalist based in Sydney. It’s where Julian Assange is expected to fly into to meet with his family on the tarmac. His wife Stella talked about she has not known him, since she met him when he was under house arrest — you know, Democracy Now! also has interviewed him over the years, from when he wore an ankle bracelet to when he got political asylum in the Ecuadorian Embassy. If you can talk about being an Australian and from Australia, your prime minister and the Parliament of Australia coming behind Julian Assange and then weighing in with President Biden each time he met with him, Antony, and what Julian Assange means in Australia?

ANTONY LOEWENSTEIN: Yeah. Thanks so much for having me, Amy and Juan.

Look, the release of Julian is a big story here, for obvious reasons. I think a lot of Australians, for years, have felt incredibly angry with the fact that an Australian citizen, Julian Assange, is being prosecuted in the U.S. under the Espionage Act. He’s not an American citizen. He’s barely spent any time in America. And I think it goes to the heart of how many Australians feel about the relationship between the U.S. and Australia. Often Australians feel like we’re — and I agree with this — a client state of the U.S. This is because of joining every single war in the Middle East, wars in Vietnam. We have a massive U.S. intelligence base, Pine Gap, in the center of Australia. Australia really is not an independent nation. And the idea of the U.S. prosecuting Julian for journalism, which was, as Trevor rightly says, what so many decent journalists do every day, speaking to sources inside government and elsewhere, was an outrage. And I think for many years a lot of Australians, the majority, in fact, of Australians, wanted him to come home.

I’m obviously glad that the current government has done that, mostly behind the scenes. I mean, for many, many years, the former government, much more conservative one, had no interest in trying to get Julian Assange home. And I think that this goes to the heart also, because I’ve been knowing WikiLeaks since 2006, when they first launched, started to get to know Julian then, from the beginning, when he launched it in Melbourne, Australia. And, really, from the beginning, his whole idea was that so much of mainstream journalism was too close to those in power. And as anyone who is a journalist or a citizen or anyone interested in accountability, there’s really no media organization, in my adult life, that has released more vital documents about the state of global power than WikiLeaks, from Guantánamo to Iraq, Afghanistan, Palestine, the drug war — so many documents, which you can access free on their website.

And I think that goes to the heart why many Australians in fact felt very proud, because in some ways in the last decades there are two major global figures of media interest from Australia: Rupert Murdoch, who’s obviously very, very right-wing, and Julian Assange, who obviously is a very, very different person. So, there’s elation in Australia today, and rightly so.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And I wanted to ask you about that, Antony, the impact of Julian and WikiLeaks on the practice of modern journalism. It seems to me that it has not been the same since WikiLeaks first came on the scene. And if you could, to speculate about the impact that he has had on the practice of reporting?

ANTONY LOEWENSTEIN: Well, it’s been profound. And obviously WikiLeaks started, really, before social media took off. I mean, 2006, there was Facebook, but it was in its infancy. And really, now every major media organization has a so-called dropbox, where people can — sources can deliver information. I think there is a much greater awareness, in at least some aspects of the mainstream press, that there needs to be more accountability and transparency around their actions. I think that’s not as much as there should be, to be clear.

And I think also what it’s done, it really ties into a larger picture of how many people in the world, really, in the Global South or the North, increasingly do not trust those in the mainstream press for not reporting the reality of what’s going on, whether it’s the war in Palestine, whether it’s the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in the last 20 years, the war on terror, Guantánamo, torture. And I think a lot of people in the public demand much more accountability from the mainstream press, but they’re not getting it.

And if you look at pretty much any public opinion poll of the mainstream press by the public, there is deep contempt for a lot of us in our profession. Not all, of course, not all, but many in the mainstream press are not treated with respect. And I think WikiLeaks, in some ways, the documents that they have released over years, now close to 20 years, I think, often has shown up the mainstream press. I think it’s why so many journalists still to this day — there have obviously been many reporters who have supported Julian over the years, to be sure, but I think a lot of journalists have been jealous. I think there’s a lot of professional jealousy around what WikiLeaks has achieved in its life.

But, obviously, what happens now is up to Julian and WikiLeaks as an organization. Who knows where it will go? But I think the legacy is very clear in the documents that they have released. Even if they release nothing else beyond this date, their legacy is set, because of the vital documents that they have put into the public domain.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to, Antony, go to the “Collateral Murder” video, shot in July 2007, leaked by Chelsea Manning to WikiLeaks. The now-infamous video showed U.S. forces killing 12 people, including two Reuters employees: Saeed Chmagh and Namir Noor-Eldeen, an up-and-coming videographer in Iraq. They were killed when they opened fire on by an Apache helicopter.

U.S. SOLDIER 1: Let me know when you’ve got them.

U.S. SOLDIER 2: Let’s shoot. Light ’em all up.

U.S. SOLDIER 3: Come on, fire!

U.S. SOLDIER 2: Keep shootin’. Keep shootin’. Keep shootin’. Keep shootin’.

U.S. SOLDIER 4: Hotel, Bushmaster two-six, Bushmaster two-six, we need to move, time now!

U.S. SOLDIER 2: All right, we just engaged all eight individuals.

AMY GOODMAN: Reuters driver, 40-year-old Saeed Chmagh, father of four, survived the initial attack. He’s seen trying to crawl away as the helicopter flies overhead. And this is footage, by the way, taken by the Apache helicopter. U.S. forces open fire again when they notice a van pulling up to evacuate the wounded Saeed Chmagh.

U.S. SOLDIER 3: Where’s that van at?

U.S. SOLDIER 2: Right down there by the bodies.

U.S. SOLDIER 3: OK, yeah.

U.S. SOLDIER 2: Bushmaster, Crazy Horse. We have individuals going to the scene, looks like possibly picking up bodies and weapons.

U.S. SOLDIER 3: Let me engage. Can I shoot?

U.S. SOLDIER 2: Roger. Break. Crazy Horse one-eight, request permission to engage.

U.S. SOLDIER 5: Picking up the wounded?

U.S. SOLDIER 3: Yeah, we’re trying to get permission to engage. Come on, let us shoot!

U.S. SOLDIER 2: Bushmaster, Crazy Horse one-eight.

U.S. SOLDIER 3: They’re taking him.

U.S. SOLDIER 2: Bushmaster, Crazy Horse one-eight.

U.S. SOLDIER 6: This is Bushmaster seven, go ahead.

U.S. SOLDIER 2: Roger. We have a black SUV — or Bongo truck picking up the bodies. Request permission to engage.

U.S. SOLDIER 6: Bushmaster seven, roger. This is Bushmaster seven, roger. Engage.

U.S. SOLDIER 2: One-eight, engage. Clear.

U.S. SOLDIER 3: Come on!

U.S. SOLDIER 2: Clear. Clear.

U.S. SOLDIER 3: We’re engaging.

U.S. SOLDIER 2: Coming around. Clear.

U.S. SOLDIER 3: Roger. Trying to —

U.S. SOLDIER 2: Clear.

U.S. SOLDIER 3: I hear ’em — I lost ’em in the dust.

U.S. SOLDIER 5: I got ’em.

U.S. SOLDIER 2: Should have a van in the middle of the road with about 12 to 15 bodies.

U.S. SOLDIER 3: Oh, yeah, look at that. Right through the windshield! Ha ha!

AMY GOODMAN: That last “ha!” In the van, it was a father who was driving his two children to school, and he had stopped to help the Reuters employee. Reuters had applied for years to try to get a hold of the video that showed the killing of their two workers, the videographer Namir Noor-Eldeen and Saeed Chmagh. They couldn’t get it. It was only when WikiLeaks released it that the world saw. It’s called by WikiLeaks the “Collateral Murder” video, again, shot in July 2007, leaked by Chelsea Manning to WikiLeaks.

And I want to go from this video, Antony, and the significance of this, that video shot in 2007, coming as a new report by +972 Magazine in Israel is just out. It’s headlined “How Israeli drone strikes are killing journalists in Gaza.” It reports survivor testimonies and audiovisual analysis reveal a pattern of strikes by Israeli UAVs on Palestinian journalists in recent months, even when they’re clearly identifiable as press. So, you’ve covered WikiLeaks. You’ve talked about their work in Iraq and Afghanistan. And you have written extensively about Gaza. Can you talk about this latest report?

ANTONY LOEWENSTEIN: Well, what’s shocking, really, since October 7 is that there’s more journalists killed by Israel in Gaza than any conflict in decades — in fact, I think pretty much any time in recorded history in the last 30 years. And that really, I think, goes to the heart of how Israel views Palestinian journalists. They actually don’t view them as journalists. They don’t view them as people who deserve protection, regardless of the vests, regardless of what work they’re doing. They see them as akin to terrorists. And that’s clear, based on that recent reporting you just mentioned, Amy, but also various other reports, including journalists that I’ve spoken to in Gaza in the last months and journalists I’ve spent time with in Gaza in the last 15 years, that Israel regards, really, so many Palestinians as legitimate targets. You don’t kill, as Israel has, 40,000 to 50,000 Palestinians, the vast majority of whom are civilians, if you don’t regard mass slaughter as the point. That is the point. The point is to kill not every single Palestinian in Gaza, but to kill huge amounts of Palestinians, including journalists, reporters.

And it’s interesting how, since October 7, as we know, not one foreign journalist has entered Gaza — in fact, one has been there very briefly, from CNN, but aside from her, no one has. And Palestinian journalists have been our eyes and ears, even though the death toll is unprecedented. And yet, despite that, there is still a sense of many in the Western elite — and, frankly, Western press — still not regarding Israel akin to, say, Russia. Russia is easily regarded as a rogue state because of its actions in, say, Ukraine. And yet somehow when we talk about Israel, who, by the way, has killed more journalists in Gaza than Russia has ever killed in Ukraine, somehow we treat Israel differently in some circles. The U.S. certainly does. Much of Europe certainly does. My country, Australia, does.

So, I think that kind of complete unaccountability within Israel is something that is going to haunt it for many years to come. There will be court cases, and many Israeli leaders are going to find that they will not be able to go to certain countries because of possible prosecution or worse. And that’s welcome. And WikiLeaks, I think, has shown in some ways a model of how there needs to be accountability and protection of journalists, because we are at a period in history now where journalists are under more threat than really ever before. Obviously, Gaza is the obvious example, but elsewhere — Ukraine, Sudan, Congo and elsewhere.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Antony, along that vein, I wanted to ask you about the hypocrisy of the press in the United States and in the West in general, that many of these media outlets are using footage from Gaza that these Palestinian journalists are largely almost totally producing, and yet they’re remaining silent about the killing of journalists by the Israelis.

ANTONY LOEWENSTEIN: And that really goes to the heart of so much of the American press. I mean, I was thinking in the last month, this White House Correspondents’ Dinner, this kind of joke of journalists getting together, palling around with Joe Biden. They talk about the importance of press freedom. What they did not talk about at that dinner a few months ago were two key things: WikiLeaks and Julian Assange, who obviously was still in Belmarsh then in London, and journalists in Gaza, who are being slaughtered on massive scale by Israel.

I mean, the idea that an American media outlet would not give the same kind of credit or presence of Gazan journalists, Palestinian journalists, to others in other countries really speaks, I think, to the heart of — I think there is still this real contempt, and, frankly, racism, at the heart of many in the American press that — not all, of course, obviously, but in many circles, there is still this unwillingness to actually recognize not just Palestinians as human beings, Palestinians as deserving protection, but Palestinian journalists, demanding accountability. I mean, where is The New York Times or The Washington Post or all these other outlets? As you say, Juan, without these Palestinian journalists, we would not have any vision in Gaza? There are no Western journalists in Gaza. And yet we rely on Palestinian journalists, who have been beyond heroic in the last eight-plus months.

And I think it really goes to the heart of how so many people, particularly younger Americans and younger people generally, regard so many people in the mainstream press with contempt. That’s why they’re getting their information often not from The New York Times, The Washington Post. They’re getting them from social media or elsewhere, which is why I think so many young people view what’s happening in Gaza and the genocide going on there as generationally defining. This is not something Israel can come back from.

AMY GOODMAN: Antony Loewenstein, we want to thank you for being with us, from Sydney, Australia, independent journalist, longtime supporter of WikiLeaks, and author of a critical book on Palestine. The book is called The Palestine Laboratory. We were also joined by Trevor Timm. Thank you, Trevor, for being with us, executive director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

But we’re going to end with the words of Julian Assange. A decade ago, 2014, I went inside the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, where Julian Assange had taken political asylum, to interview him. He had been holed up there for more than two years at that point, having received political asylum from the government of Ecuador, but could not make it to Ecuador without being arrested. Toward the end of our interview, I asked Julian Assange, “What gives you hope? And what do you see is the greatest legacy of WikiLeaks?” This was Julian’s response.

JULIAN ASSANGE: Well, hopefully the greatest legacy is still to come. But WikiLeaks started in 2007, but it was really this very public confrontation that we had in 2010, 2011, which people saw watching. So it was not — a new generation saw history unfolding in real time, before their eyes, a history that they were part of. Young people see the internet as their place, where they exchange ideas and culture and so on. And previously, they had been politically apathetic, because they didn’t feel that they could be a part of the power process. But seeing Hillary Clinton’s personal cables and equivalents for many different countries, and the fight that we were in, and being part of that in some way, by spreading this information or talking about it with others, educated a new generation. And the internet went from being a politically apathetic space to being a political space. And that then spread into many different things. And so, I think this is actually the most significant thing that we have done.

We have also, in terms of the publishing industry, widened the envelope of what is acceptable to publish and so on. That’s been quite important and set off a cascade of examples, which — going through allegedly Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden and Jeremy Hammond and many others, to come forward and reveal abuses in government.

AMY GOODMAN: Is there another Edward Snowden in the pipeline?

JULIAN ASSANGE: I’m sure — I’m sure there will be. In fact, I’m sure there already is.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that’s Julian Assange a decade ago in the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. He would then be taken by the British police to Belmarsh Prison. He has just been released from there after five years. Soon we will be broadcasting Julian Assange speaking for himself in his own words, either in Saipan, where he’ll go to a U.S. district court and plead guilty to one felony, and then head home to Sydney, Australia, to rejoin his family.

When we come back, low-income advocates are joining climate activists here in New York to demand Democratic Governor Kathy Hochul reverse her shocking decision to cancel the city’s congestion pricing program that was just set to start. We’ll be back in 20 seconds.

Media Options