A political crisis is growing in Brazil after The Intercept revealed that the judge who helped jail former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva likely aided federal prosecutors in their corruption case in an attempt to prevent Lula’s Workers’ Party from winning the presidency. Leaked cellphone messages among Brazilian law enforcement officials and other data obtained by The Intercept point to an ongoing collaboration between Judge Sérgio Moro and the prosecutors investigating a sweeping corruption scandal known as Operation Car Wash. Lula was considered a favorite in the lead-up to the 2018 presidential election until he was put in jail and forced out of the race on what many say were trumped-up corruption charges. The leaked documents also reveal prosecutors had serious doubts about Lula’s guilt. The jailing of Lula helped pave the way for the election of the far-right former military officer Jair Bolsonaro, who then named Judge Sérgio Moro to be his justice minister. We get an update from Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Glenn Greenwald of The Intercept, whose reporting is based on a trove of internal files and private conversations from the prosecutorial team behind Operation Car Wash.

Transcript

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: A political crisis is growing in Brazil after The Intercept revealed that the judge who helped jail former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva likely aided federal prosecutors in their corruption case in an attempt to prevent Lula’s Workers’ Party from winning the presidency. Leaked cellphone messages among Brazilian law enforcement officials and other data obtained by The Intercept point to an ongoing collaboration between Judge Sérgio Moro and the prosecutors investigating a sweeping corruption scandal known around the world as Operation Car Wash.

Lula was considered a favorite in the lead-up to the 2018 presidential election until he was put in jail and forced out of the race on what many say were trumped-up corruption charges. The leaked documents also reveal that prosecutors had serious doubts about Lula’s guilt. The jailing of Lula helped pave the way for the election of the far-right former military office Jair Bolsonaro, who then named Judge Sérgio Moro to be his justice minister.

AMY GOODMAN: The Intercept's reporting is based on a trove of internal files and private conversations from the prosecutorial team behind Operation Car Wash. The Intercept has dubbed the files “The Secret Brazil Archive.” As a result of The Intercept's reporting, Brazil’s Supreme Court has announced it will reconsider an appeal by Lula to be released from prison. Calls are also growing for Sérgio Moro to resign as justice minister. The Brazilian Bar Association has called for Moro to be suspended and for all prosecutors involved in the Car Wash scandal probe to be disbanded.

Moro has denied any wrongdoing, claims the messages have been taken out of context. Moro wrote in a statement, quote, “I lament the lack of indication of the source of the person responsible for the criminal invasion of the prosecutors’ cell phones. As well as the position of the site that did not contact me before the publication, contrary to basic rule of journalism. As for the content of the messages they mention, there is no sign of any abnormality or providing directions as a magistrate, despite being taken out of context and the sensationalism of the articles,” he said.

Vermont senator, 2020 presidential candidate Bernie Sanders told The Intercept, “Today, it is clearer than ever that Lula da Silva was imprisoned in a politicized prosecution that denied him a fair trial and due process. During his presidency, Lula oversaw huge reductions in poverty and remains Brazil’s most popular politician. I stand with political and social leaders across the globe who are calling on Brazil’s judiciary to release Lula and annul his conviction,” Senator Sanders said.

We go now to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, to speak with the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Glenn Greenwald of The Intercept, who broke the story.

So, Glenn, lay out what you exposed in this three-part series. Looks like Glenn is having a little trouble hearing us, so we’re going to go to break, and we’ll come back to Glenn Greenwald in Rio de Janeiro. Stay with us.

[break]

AMY GOODMAN: Damon Locks and Black Monument Ensemble performing “Sounds Like Now.” This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González. Our guest is Glenn Greenwald, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, founding editors of The Intercept, just published “The Secret Brazil Archive,” a three-part exposé revealing that the judge overseeing the case that put former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva behind bars likely aided the federal prosecutors in their case against Lula and other high-profile figures.

Lay out you found in this three-part report, Glenn, and how it’s rocking Brazil right now.

GLENN GREENWALD: Sure. So, as your audience likely knows, because I have discussed it with you many times and you’ve covered it with other guests, Brazil is a country that has been swamped by multiple political crises—the impeachment of former Workers’ Party President Dilma Rousseff, who succeeded Lula, the ascension of this far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, economic crises and the like.

But by far the biggest event in Brazil was the imprisonment last year of former President Lula da Silva, not just because he was such a giant on the world stage democratically, which he is, because he was elected overwhelmingly twice, in 2002 and 2006, and his presidency was so successful in lifting millions of people out of poverty, in transforming Brazil, that he left Brazil and—left office, I mean, with an 87% approval rating, which is unheard of. So, to put somebody like that in prison is an earth-shattering story in and of itself, but it was made all the more consequential by the fact that all polls showed that Lula, who was running again for president last year—he was term-limited out of office the first time—was the overwhelming favorite, was the massive front-runner, was ahead by 20 to 30 points in every poll, including ahead of Jair Bolsonaro. And so, to imprison Lula meant that he was rendered ineligible under the law to run, and that’s what paved the way ultimately for Jair Bolsonaro’s ascension to control over Brazil, which is the fifth most populous country in the world, with massive oil reserves and the most important environmental resource on the planet, which is the Amazon, all of which is now in the hands of Jair Bolsonaro.

This was done by a task force prosecutors and a judge, Sérgio Moro, who have basically been turned into superheroes, into deities, by the Brazilian press and by the world press. Sérgio Moro was heralded around the world as some great figure. He was named to the Time 100 list in 2016 and went to the gala in New York. He had a huge profile on him on 60 Minutes that was a puff piece, basically turning him into this noble anti-corruption figure. And there’s been almost no questioning of anything that they’ve done, even though they’ve been using highly questionable practices.

Here in Brazil, there has been a longtime suspicion that they in fact were abusing their powers for political ends, that what they really were, were right-wing ideologues and operatives who were abusing the law to destroy the Workers’ Party—one of the only left-wing parties in the entire democratic world that has dominated politics in a major country and has succeeded in anti-poverty programs—in order to usher in the pro-right faction into power, that they were abusing the law to basically put the leaders in prison to destroy the party. They’ve always vehemently denied this. They’ve said, “We have no ideology. We have no party preference. We don’t care who wins elections. We’re only neutral judges and prosecutors applying the law.”

The archive that was provided to us by our source, this massive trove of secret documents, about their internal communications, about their internal actions, their chats, their audios, their videos, an archive that, as I’ve said, is bigger in size than the Snowden archive was, which until that point was the largest leak in the history of U.S. journalism, bigger than that, finally enables us to see the truth about what they really did.

And the three stories that we published on Sunday, the reason they’ve shaken Brazil to the core is because Sérgio Moro, after Bolsonaro won, thanks to Justice Moro putting Lula in prison, became the second most powerful person in Brazil, because Bolsonaro created what he called a “super justice ministry,” that Sérgio Moro now runs. He’s the justice minister of the country. It’s like being an attorney general but on steroids, controlling all law enforcement, surveillance, police actions.

And what this material shows are three key things. Number one, it shows that inside the prosecutor task force, they were talking openly about how they wanted to make sure that the Workers’ Party lost the election. And we can talk about the specifics, but, in particular, there was a judge who authorized Lula to give an interview from prison 12 days before the election. And they panicked, and they said, “We need to stop this, because if Lula is allowed to be heard from, he will—there’s a good chance he will make PT win the election, and we need to put a stop to this.” They said they were praying every day that PT doesn’t return to power—PT being the Workers’ Party. So, this five-year claim that they had—”we don’t have any preferences for parties, we don’t care who wins elections”—was an absolute lie. They were talking openly and explicitly about how their top priority was making sure PT didn’t win the election—exactly what people have been accusing them of.

Secondly, just like in the U.S., a judge is required to be neutral. A judge can’t favor one side or the other. And there’s long been a suspicion that Judge Moro, when he was ruling on these cases, like finding Lula guilty, finding other left-wing leaders guilty and people from other parties guilty, that he was in fact collaborating in secret with the prosecutors to design the case. They vehemently and angrily denied this accusation. The head of the prosecutorial task force, who’s a national hero in Brazil, Deltan Dallagnol, wrote a book in which he said, “These accusations are outrageous. They’re disgusting.” We have video of Judge Moro being asked about this, and he was so angry about it that he actually scoffed at it with a smile, saying, “People talk about this as being—as though it’s Judge Moro’s prosecution or Judge Moro’s strategy.” He said, “People don’t understand. Judges in Brazil have no role in prosecuting people. Our value is one of passivity. We simply listen to both sides, listen to the evidence and make decisions.” What the conversations that we published show, between Judge Moro and head of the prosecutorial task force, is that Judge Moro in fact was constantly directing, constructing, designing the entire prosecution, screaming at them when they were doing things that he thought were wrong, telling them how to better fortify the case, not just against Lula, but against other people. He was basically the commander of the prosecutorial team and then walking into court as though he were sitting judging Lula’s case and others as a neutral arbiter. So, everything that they vehemently denied to the public they were doing, in fact, they were doing for years, as these documents show.

And the third key revelation, as you said, is that the specific case for which they prosecuted Lula, namely the charge that he had received a—what they call a triplex apartment, in order to make it sound very glamorous, when in fact it’s kind of rundown and shoddy, and Lula had the capability to buy it 100,000 times over if he wanted—but the charge was he received this triplex apartment and renovations to it in exchange for helping this construction company get contracts, that they knew themselves, three days before they indicted him, that they didn’t have the evidence sufficient to show his guilt or even to justify why this case belonged with them. But they just decided they were going to go forward anyway, because they knew they had a judge, in Judge Moro, now Minister Moro, single-mindedly devoted to the goal of imprisoning Lula, and not just imprisoning him, but doing so in time to make him ineligible to run for 2018’s election, out of fear that PT would win the election.

So, the consequences of this revelation have been enormous, because Moro, as I said, is the second most powerful person in Brazil, after Bolsonaro, but he’s by far the most respected person, or at least was the most respected person. And even his most ardent and loyal defenders, in light of these revelations, have said there’s no way to defend this conduct. One of the biggest right-wing newspapers in Brazil, Estado de São Paulo, that has spent four years praising and heralding an cheerleading for Sérgio Moro, came out and said he needs to resign, and the head of the task force needs to be fired, just based on the first three stories that we published. And that’s indicative and reflective of widespread sentiment. And that’s why it’s shaking Brazil to the core, because Sérgio Moro is crucial to the legitimacy of the Bolsonaro government.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Well, Glenn—

GLENN GREENWALD: Getting him to go join the government was a crucial part.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Glenn, I wanted to ask you, because these are, obviously, very explosive conclusions that you’ve reached on your reporting. Could you talk a little bit about the archive sources that you have? In other words, I could understand the cellphone texts, let’s say, between different parties involved in this being leaked, but you were even talking about audio. How was the audio compiled? Were these people taping their own conversations? Could you discuss a little bit the nature of the documents that you have?

GLENN GREENWALD: Sure. So, when I say audio, generally what I mean is—and we haven’t published any of the audios yet, so I’m reluctant to say much about them. But when I say audios, typically what I mean is not that they were taping their own conversations, but that they often communicated with one another using apps on telephones that enable you to either type out messages to people, so you text messages to people, or you can leave voicemail messages for people, essentially. So, instead of typing some long message, you just click microphone on your telephone, you speak as a monologue, and you leave a message that way on somebody else’s phone, which is a very common thing to do for people who use WhatsApp or Telegram or Signal. Those are the kinds of audios that I’m talking about. But because oftentimes, especially for complicated matters, you don’t want to type huge paragraphs, you just want to speak, much of their communications—although it’s not really technically taped, you end up getting a huge part of their conversation, because they’re speaking to one another in one-, two-, three-minute monologues back and forth to one another. Those are the kinds of audios we have.

AMY GOODMAN: So, I wanted to turn to a video you tweeted Monday of Sérgio Moro speaking in 2016. He was a federal judge at the time.

JUDGE SÉRGIO MORO: [translated] Let’s make something very clear. You hear a lot about Judge Moro’s investigative strategy. I often say the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the Federal Police and the subsidiary bodies are the ones responsible for that. I don’t have any investigative strategy at all. The people who investigate or who decide what to do and such is the public prosecutor and the Federal Police. The judge is reactive. We say that a judge should normally cultivate these passive virtues. And I even get irritated at times. I see somewhat unfounded criticism of my work, saying that I am a judge investigator. I say go ahead and identify them. In my judicial decisions, a decision where I determine the production of legal proof without provocation, at most, I put together some documents for the eventual testimony of a witness. In this large haul of criminal cases, that’s practically nothing.

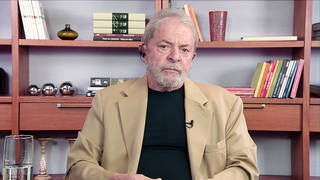

AMY GOODMAN: And now I want to turn to former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in his own words, appearing on Democracy Now! in March 2018, just before he was jailed.

LUIZ INÁCIO LULA DA SILVA: [translated] Now, if my innocence is proven, then Judge Moro should be removed from his position, because you can’t have a judge who is lying in the judgment and pronouncing as guilty someone who he knows is innocent. He knows that it’s not my apartment. He knows that I didn’t buy it. He knows that I didn’t pay anything. He knows that I never went there. He knows that I don’t have money from Petrobras. The thing is that because he subordinated himself to the media, I said, in the first hearing with him, “You are not in a position to acquit me, because the lies have gone too far.” And the disgrace is that the one who does the first lie continues lying and lying and lying to justify the first lie. And I am going to prove that he has been lying.

AMY GOODMAN: So, that is now-jailed former President Lula da Silva. The Brazilian Bar Association has called for Moro to be suspended and for all prosecutors involved in the scandal to be disbanded. Yet, as you’ve pointed out, Bolsonaro made him a kind of super justice minister, bringing together the functions of law enforcement, surveillance and investigation, which were distributed to several ministries, all under Moro’s super justice minister position, making him, as you pointed out, Glenn Greenwald, the second most powerful person in Brazil now. So what happens?

GLENN GREENWALD: So, it’s so fascinating, Amy, because the story reminds me so much of the Snowden story in so many ways. One way, remember, that the Snowden story essentially began when Snowden heard James Clapper go before the Senate and just look at them and just lie to their faces, when he was asked, “Are you collecting data about millions of Americans?” and he said, “No, sir, we’re not doing that. We have no such program.” And it was shocking to Snowden to watch somebody in that high of a position so sociopathically lie, and that’s the thing that finally drove Snowden to decide, with finality, “I need to show the truth.” That’s the same reaction I have when I listen to Judge Moro look in the cameras and say, “I get irritated at the notion that I have any involvement in a prosecution,” when I’ve now read all of the years’ worth of documents and conversations that we’ve—a lot of which we’ve published, and will continue to publish, showing that he did exactly what he looked in the camera, and with this smirk, and just so smugly denied. It’s just amazing, even though I guess it shouldn’t be, the willingness of people in these high positions of authority to so sociopathically lie about what it is that they do.

And then the second issue is, you know, just like in the Snowden story, where people for years suspected that the NSA was spying, but were called conspiracy theorists or paranoid people, and then the evidence proved them right, everybody—or, a lot of people in Brazil have long said what Lula said—namely, that Moro got into a position where he was forced to convict Lula, where he was single-mindedly obsessed with it. The Brazilian elites were demanding that of him, and therefore he was willing to do anything, including breaking rules, breaking laws, in order to make that happen. They were called conspiracy theorists. They were called paranoid. They were called left-wing liars and ideologues who were only saying that to protect their leader. And as it turns out, what Lula said in that interview is absolutely right.

And, of course, the conviction that Sérgio Moro issued, notwithstanding the fact that it was very quickly, very strangely quickly, affirmed by an appellate court, in time to make him ineligible to run, is now called into doubt, because we know, because we’ve all seen the evidence, that the process that led to his conviction was deeply and inherently corrupted in the most basic way, because the person who found him guilty was doing exactly that which judges are prohibited from doing. And the Supreme Court will now decide whether that conviction can be maintained in light of what we’ve shown.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Glenn, I wanted to ask you, in a broader sense, this whole issue of corruption in government, and prosecutors removing or being able to jail or remove elected officials or key political leaders—clearly, in a democracy, in an industrial or Western democracy, there’s two ways to remove a leader: You vote them out of office, or you get them indicted and jailed and removed that way. To what extent is this a signal to people around the world, in other countries, about the kind of skepticism that you should have about investigations coming at the top leaders? And, of course, I’m sure there are people in the—Trump supporters here in this country, who would point to the FBI agent Peter Strzok and Lisa Page, the FBI counsel, as they were attempting to help remove Trump from office. But to what degree do you—is this a warning for people in other countries to be wary and skeptical, even in the face of what seems initially to be damning evidence against a political leader?

GLENN GREENWALD: Yeah, I mean, look, Juan, you know, as you know, as you guys know, I’ve been one of the people, along with Noam Chomsky and Matt Taibbi and a few lonely others on the left, who have been skeptical of the Russiagate story, in part because we know that these agencies have a long history of lying. And the FBI and the CIA and the NSA in the U.S. were vehemently opposed to Donald Trump and wanted Hillary Clinton, because they trusted her much more. And so there was a concern always, on my part, that they were abusing their prosecutorial powers to interfere in our domestic election in the United States in order to help the candidate they wanted to win and hurt the candidate that they wanted to lose. There were other factions in the FBI, by the way, who wanted Donald Trump to win desperately, and did their own abuse of power to hurt Hillary Clinton’s chances and help Donald Trump win. So there were two different factions inside these law enforcement agencies interfering in the U.S. election by abusing their power to help the two candidates they preferred, which is an incredible—that was the real meddling that was dangerous in the 2016 election.

And, of course, the parallel is very clear, which is that in Brazil, since 2002, the center-right, the oligarchical class, which, by the way, got kind of comfortable with Lula and PT, but nonetheless still wanted the center-right to be in power—and I asked Lula about that: “Why would the elite be so opposed to you, when the elite thrived under your presidency? Even though you lifted millions of people out of poverty, you weren’t a socialist. You weren’t Castro. You weren’t Chávez.” The markets in Brazil, the rich in Brazil prospered under Lula. And he said it was cultural. They hated the fact that somebody who came from poverty was in the presidency, who doesn’t speak perfect Portuguese, who didn’t read until he was 10. They hated seeing in airports people who used to be invisible in the favelas now able to fly to visit their family, to be able to buy apartments. They hated it culturally. They felt like their Brazil was being taken away from them. And so, they couldn’t beat Lula, they couldn’t beat the Workers’ Party democratically, and so they abused the force of law in order to destroy the party that they couldn’t beat politically. And this is a serious warning and a serious danger about why anytime people in power exercise power in secret, we need to be skeptical of them—all human beings.

And I believe that these prosecutors began with good intentions. Brazil really is a country that has been plagued by corruption, on the left and the right, for a long time. They’re young people. They’re in their thirties. I believe they began with good intentions. But they became so drunk on their own power. Nobody was questioning them. The large media here in Brazil, with the exception of Folha, one newspaper, stopped questioning what they were doing, just applauded for them, served as their tool. When you have that kind of faith being put into you, that kind of unquestioned power, as I’m not hardly the first person to observe, that kind of power corrupts people. And they got corrupted. They became politicized. And they became drunk on their own belief in their own goodness, that they thought they were above the law and could break the rules, because their ends justified the means. And it is an important lesson to learn about power in general.

AMY GOODMAN: And, of course, they ousted, impeached Dilma Rousseff, before they imprisoned Lula. Finally, Glenn, very quickly, you’ve got this three-part series. It’s rocking Brazil right now—calls for Moro to go down, the super justice minister; calls for Lula to be released. What do you think is the chance of this? And finally, you’re saying this is larger than a Snowden cache of information. You have much more information that you haven’t released. What are you doing with it?

GLENN GREENWALD: We are working feverishly to publish it as quickly as we can. Obviously, you know, there is a lot of desire to see more of it, but we have a responsibility, just like we did with the Snowden case, to make sure that what we’re publishing is done well and professionally and accurately, because if we make a single mistake, they’ll use that forever against us to undermine the credibility of the reporting. But definitely more is coming, very soon.

So, when you ask what’s going to happen with Moro, what’s going to happen with Lula, a lot of it depends on how good of the reporting we do and how much more we show, which we have a lot more to show. But I believe, even with just what we’ve shown—I’m not saying Sérgio Moro is about to be put out of office, because he still has the support of Bolsonaro. He’s still crucial to the government. But certainly he’s severely damaged and weakened, and will continue to be more damaged and weakened as we reveal more. I’m not sure he can survive that. But I do think there’s a good chance that the Supreme Court will say that the conviction of Lula da Silva was a byproduct of so much impropriety that we cannot let it stand, that at the very least he needs a new trial and needs to be let out of prison while this new trial proceeds.

AMY GOODMAN: Glenn Greenwald, we want to thank you for being with us, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, one of the founding editors of The Intercept, has just published “The Secret Brazil Archive.” We’ll link to it at democracynow.org.

When we come back, we look at the horrific conditions for immigrants in for-profit detention jails around the United States with Aura Bogado. Stay with us.

Media Options