The Oscar-nominated documentary Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat recounts the events leading up to Black American jazz musicians Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach’s 1961 protest at the United Nations of the CIA-backed killing of Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba. The first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lumumba was an icon of the Pan-African and anti-colonial movements. He was tortured and killed shortly after the formation of the first government of independent Congo following a military coup supported by Belgium, the United States and powerful mining interests. Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat's Belgian director Johan Grimonprez explains that Lumumba's assassination was “the ground zero of how the West was about to deal with the riches of the African continent.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: We turn now to the Oscar-nominated documentary Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat. Told entirely through archival footage, the film is a sweeping story of the events leading up to the pivotal chapter in Congo’s history, the 1961 assassination of the Congolese president, the independence leader Patrice Lumumba, the film tracing the long, brutal history of mineral exploitation in Congo, from the time when the Congo was a possession of the Belgian King Leopold II all the way to the conflict minerals of today, showing the power of the mining industry, highlighting the role of the Belgian mining company Union Minière in the overthrow and murder of Lumumba. Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat features several key leaders at the time, including President Eisenhower, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, former U.N. Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld, as well as the jazz legends Abbey Lincoln, Max Roach, Nina Simone, Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong. This is a trailer.

NEWSREEL: One of America’s most popular emissaries arrives in the troubled Congo on a State Department goodwill mission. Louis’s solid swinging outraged Radio Moscow, which blasted Armstrong’s visit as a diversionary tactic.

PRESIDENT DWIGHT EISENHOWER: The people of the Congo are entitled to build up their country in peace and freedom.

LOUIS ARMSTRONG: [singing] Hold me close and hold me fast.

LARRY DEVLIN: We were to go to Élisabethville to attend a concert given by Louis Armstrong.

WILLIAM FRYE: How much money do you suppose the Central Intelligence Agency has poured into the Congo?

MENNEN WILLIAMS: I don’t know. Are you prepared to say?

WILLIAM FRYE: I certainly, of course, don’t know. I wonder if it’s quite honest to represent our policy as completely angelic.

LARRY DEVLIN: And seated out on the terrace was a man I recognized. He said, “Well, you have to assassinate Lumumba.”

INTERVIEWER: He used those words?

LARRY DEVLIN: Yes.

INTERVIEWER: But who ordered him?

LARRY DEVLIN: He said President Eisenhower.

DIZZY GILLESPIE: In the U.N., when Khrushchev took off his shoe and was beating that shoe, and the interpreter said, “I’ll bury you!” taking about America, Khrushchev was saying, “I love you.” But it was the interpreter who hated America. You understand what I mean?

INTERVIEWER: But did he have rhythm.

DIZZY GILLESPIE: Rhythm is my business.

NIKITA KHRUSHCHEV: [translated] Death to colonial slavery! Bury it! Bury it deep in the ground! The deeper, the better!

AMY GOODMAN: The trailer for Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat, nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary. I just interviewed the director of the film, the Belgian filmmaker Johan Grimonprez, and began by asking him why he made it.

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: Well, it roots back in the ignorance, not knowing and growing up in Belgium, but not learning that story in school. And so, here we have war being privatized and the template of a corporatocracy that is dictating what sort of happens in the war industry. You could actually project that template exactly on what was going on with that pivotal moment when Congo became independent. And so, it’s the mining industry, specifically Union Minière, going back to Société Générale, that was actually complicit in the overthrow of Patrice Lumumba and, ultimately, subsequently, his assassination.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us the story of King Leopold and the Congo and then Congo’s independence.

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: Well, for example, Union Minière du Haut-Katanga was a private company by Leopold II. He actually — the Free State of Congo was his personal property. And so, what we see in that sort of moment towards independence, still sort of a lot of stuff is lingering. The Union Minière was actually holding — having a huge hold over the country. And so, when Patrice Lumumba became the first independent leader of the Congo, Union Minière concocted — or, actually succeeded in the province of Katanga installing a marionette president, Moïse Tshombe, to actually get back at Patrice Lumumba, reconquering the Congo in a sort of a neocolonial grab. You know, people talk about postcolonialism, but actually it’s a misnomer. What was sort of the ground zero of how the West was about to deal with the riches of the African continent was actually the assassination of Patrice Lumbumba.

AMY GOODMAN: And talk about what the Black U.S. jazz musicians have to do with the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: Well, the context is that we have the 15th General Assembly, right? Sixteen African countries are admitted to the world body, and it actually causes a global shift, a political earthquake within that world body, where 16 African countries actually make that, the global shift. Sort of the Afro-Asian bloc suddenly gains the majority vote in the United Nations.

AMY GOODMAN: They become independent countries, these African countries.

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: They’re admitted to the world body as independent countries, and it shifts the global vote. The Afro-Asian bloc is actually gaining a majority vote. And so, we have East and West sort of trying to wrestle control over the United Nations General Assembly. Nikita Khrushchev would introduce the decolonization resolution to get the Global South on his case — Nikita Khrushchev, the then-Soviet premier of Russia. And then we have the United States, ruled by President Eisenhower, would send in arm twisters to actually buy up votes within the United Nations General Assembly. But also, subsequently, one month later, they would send Black jazz ambassadors into the Congo. It was the United States Information Agency, already before was sending Black jazz ambassadors out.

AMY GOODMAN: So, USIA, the U.S. Information Agency —

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: United States Information Agency.

AMY GOODMAN: — is sending Black jazz musicians to the Congo.

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: It was a strategy that was already mid-’50s. It was a way to actually win the hearts and minds of the Global South. But I discovered that, for example, Dizzy Gillespie was sent to Syria; underneath, you had actually the CIA buying up of the Syrian government. Like with Louis Armstrong arriving in the Congo one month after the General Assembly, the United Nations 15th General Assembly, you see that actually the United States, in cahoots with the Belgian intelligence, is actually plotting to overthrow the Lumumba government and also subsequently assassinating Patrice Lumumba.

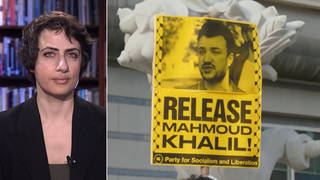

AMY GOODMAN: I want to actually go to that moment at the end of the film. It’s announced that Patrice Lumumba has been assassinated. And we’ll talk about who was involved with his assassination. But it’s from February 15th, 1961, when protesters, led by the jazz great Abbey Lincoln, led by Max Roach and the great writer Maya Angelou, stormed the U.N. Security Council to protest the murder of Patrice Lumumba.

ADLAI STEVENSON II: Shall the United Nations survive? Shall the attempt to bring about peace by the concerted power of international understanding be discarded?

PROTESTERS: Murderer! Lumumba! Murderer! Lumumba! Lumumba! Killers! Murders! Assassins! Slave drivers! Bigoted [bleep]! You Ku Klux Klan [bleep]!

AMY GOODMAN: It’s an incredible moment. “You bigoted MFers,” they’re yelling. They’re comparing them to the KKK. And that was the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Adlai Stevenson under John F. Kennedy. He was giving his maiden speech?

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: And it was immediately interrupted by 60 protesters, in the lead by Abbey Lincoln, the jazz singer, in sort of conjunction with the Women’s Writer Coalition in Harlem, amongst Maya Angelou and Rosa Guy. And they crashed the Security Council to protest the murder. This is three days — you know, you have to know that Patricia Lumumba was murdered three days before President Kennedy became president, as well. And so —

AMY GOODMAN: He was elected, but it was January 17th, so it was before his inauguration, right?

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: Exactly. Exactly.

AMY GOODMAN: So this is under Eisenhower this took place.

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: Exactly.

AMY GOODMAN: The previous president.

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: But the protest, because they kept it quiet one month, and then it was announced at the Security Council, 15th of February, 1961.

AMY GOODMAN: So, the soundtrack — of course, it’s called, Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat. The soundtrack of this documentary, the jazz greats of the United States, and, as you talked about, recruited by the USIA, the U.S. [Information] Agency, to play in Africa. So, talk about their role, like Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, and what they understood they were being used for.

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: Well, you see that, actually, the Black jazz ambassadors were sent out as a cover for actually coup d’états that were plotted underneath, hence also the title, Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat. So, you have Louis Armstrong, actually, upon invitation by Sengier, who was the CEO of Union Minière, the company, that actually propped up Moïse Tshombe, the then-marionette president in Katanga, which was used to secede from Lumumba’s sort of greater Congo and to actually cause a rift. We have Patrice Lumumba — Louis Armstrong arriving third week of October. Then he comes back in Katanga third week of November. You have to know, actually, he was staying at Moïse Tshombe’s, the then-marionette president in Katanga, in his house. And so, that night, they have dinner, Larry Devlin, Louis Armstrong, U.S. Ambassador Timberlake —

AMY GOODMAN: Wait. Explain who Larry Devlin was.

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: Larry Devlin was head of the CIA. But unbeknownst to Louis Armstrong, to him, he was an agricultural adviser. That was his cover name. And there was also U.S. [Ambassador] Timberlake, and we have the Belgian advisers, d’Aspremont Lynden, who was the African minister, Belgium Africa minister. And he’s sitting at the table. But still, you know, you would think that they would be sent out as passive instruments of promoting democracy, which is very schizophrenic, because back home, they were not allowed to vote. They were still second-rate citizens.

AMY GOODMAN: You mean the jazz musicians were not allowed to vote in the United States.

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: Exactly. It’s very schizophrenic. You know, it’s very schizophrenic. But it’s not because they are used as propaganda instruments to promote democracy. They actually were very much also, you know, not passive agents. You know, he would grill Moïse Tshombe and say, “You’re in bed with big money. You know, you have to take some and give some,” or he would refuse to go play for an apartheid audience in South Africa, or he would change lyrics. I think that’s very subtle. He would change the lyrics in the song that he also sung when he visited Ghana and sung for Kwame Nkrumah, the first independent leader of Ghana, the “Black and Blue” label. He would sing, instead of “I’m white inside,” he would change the words to “I’m right inside.” Or even at one moment with the Little Rock, he would be very outspoken and refuse to go as a diplomatic ambassador to Russia, and say, you know — and it’s quoted from The New York Times — you know, he said, “The government can go to hell.” So he was very outspoken in 1957. Later on, it was a bit more tricky, because his concerts were still being bombed, for example, in Knoxville, after he came back from Africa, by white supremacists.

AMY GOODMAN: One of the people who worked as an adviser on this film worked on Raoul Peck’s great 2000 film Lumumba. That was like a quarter of a century ago. What new information has come out? You mentioned Larry Devlin, CIA; Eisenhower, the president of the United States at the time. What did the CIA and Eisenhower have to do with Lumumba’s murder?

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: Well, a lot of new data came out with the publication of Ludo De Witte’s book The Assassination of Patrice Lumumba in 1999, that actually also the United Nations, and more specifically, Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld, was complicit in this whole affair of the downfall of Patrice Lumumba. Of course —

AMY GOODMAN: So, Dag Hammarskjöld was the U.N. secretary-general at the time.

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: At the time. He was complicit with the downfall of Lumumba, and, ultimately, the capture, but then also the assassination. Then, also, the monarchy was in the know about what was going on, that Lumumba was about to be sent over to Katanga. Mobutu was in the know. The Belgian Sûreté, at the time was called, the Belgian intelligence, was involved, and they actually labeled Patrice Lumumba as a communist to get actually the United States in their camp on the cause. And so, President Eisenhower, afraid that the NATO, sort of the Western union of countries, that would fall apart, he actually sided with the colonial countries, in essence, right?

And so, you know, at the time, he — you know, that came out in the Church Committee in 1976. There was a hearing in the mid-’70s where a lot of that stuff came out. First, there was actually the plotting to actually get rid of Fidel Castro. But then they changed gear, and then Patrice Lumumba became a priority, because they were afraid he would become sort of siding with Nikita Khrushchev, the then-Soviet premier. And so, they all banded together to actually assassinate him. And this was the first democratically leader of the Congo.

And why? Because in the beginning of the film, you hear Patrice Lumumba literally saying, “I’m not a communist or a socialist. I’m actually African. I’m, first of all, a sovereign leader who actually chooses that the riches of the country also benefit the country.” And at the end of the film, you see the conclusion of Malcolm X, as well. He says, you know, “It’s not socialism or Marxism or communism they’re afraid of. It’s Africanism.” It’s actually a leader choosing to stand up and choosing that the riches would also come back to the population.

But if you look at sort of what is the Congolese algorithm, the Belgian Congolese writer In Koli Jean Bofane, he would sort of — what he would call the template, the Congolese algorithm, that actually all conflicts that were used in all major wars of the 20th century were sourced from the Congo, be it copper, be it uranium, rubber in the beginning of the First World War, uranium in the Second World [War], because it was high-grade uranium. Like, 3,000 ton that was used in the Manhattan Project came actually from Katanga, from the east.

AMY GOODMAN: And how did the U.S. get it to make the atomic bombs, the uranium from Katanga, from the Congo?

JOHAN GRIMONPREZ: It was ultimately a deal with Henri Spaak, because, you know, Belgium was overrun by the Germans, and so we had a Nazi government at that time. So, the king fled, and then Spaak, the prime minister, fled to London. And together with Churchill and Roosevelt, the president of the United States, they actually sort of made a deal that all uranium from the Belgian Congo would actually be part of the Manhattan Project, basically. And, you know, that was 3,000 ton, 70% high-grade uranium. Half of that was still above ground when Lumumba took power. So, that was part of the equation, what was going on in Katanga.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Belgian filmmaker Johan Grimonprez, director of Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat, which has been nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary. Told entirely through archival footage, the film is a sweeping story of the events leading up to the assassination of the Congolese independence leader, first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba. To see the whole interview, go to democracynow.org.

You can also see other interviews Democracy Now! has conducted about other films nominated for this year’s Oscar, including the Palestinian Israeli film No Other Land, also nominated for best documentary, about the Palestinian community of Masafer Yatta, which was recently attacked by Israeli settlers. There’s also the best short documentary I Am Ready, Warden about the death penalty, that began when a Texas man asked journalist Keri Blakinger to witness his execution, and The Apprentice, nominated for best actor and best supporting actor, the film many say Trump doesn’t want you to see, that looks at how Trump was mentored by Roy Cohn, former chief counsel to Senator Joseph McCarthy during the Red Scare. Trump, he mentored, as he built his New York real estate empire. That does it for our show. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks so much for joining us.

Media Options