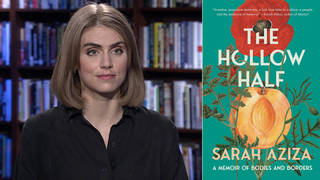

The award-winning Palestinian American journalist and author Sarah Aziza has released a new book, The Hollow Half: A Memoir of Bodies and Borders, in which she examines her recovery from an eating disorder from which she nearly died in 2019, linking it to the generational trauma experienced as part of her Palestinian family’s history of exile. Aziza was born in the U.S. as a daughter and granddaughter of Gazan refugees. “I began to recover memories of my Palestinian grandmother that led to a curiosity … about my family’s history in Gaza, in Palestine, the greater Nakba,” says Aziza. “And as a daughter of the diaspora, I hadn’t tied my own story so viscerally to the story of my people.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

The International Court of Justice is holding a weeklong hearing on Israel’s obligations to provide aid to Gaza. On Monday, Palestinian envoy Ammar Hijazi accused Israel of using humanitarian aid as weapons of war as Israel continues its devastating blockade.

AMMAR HIJAZI: That’s really the heart of why Palestine and over 40 other states are addressing the court today. It is not about the number of aid trucks Israel is or is not allowing into the Occupied Palestinian Territories, especially Gaza. It is not about Israel destroying the — it is about Israel destroying the fundamentals of life in Palestine while it blocks U.N. and other humanitarians from providing lifesaving aid to the population. It is about Israel unraveling fundamental principles of international law, including their obligations under the U.N. Charter. It is about Israel turning Palestine, and particularly Gaza, into a mass grave for Palestinians and those coming to their aid.

AMY GOODMAN: We end today’s show with a new memoir by the award-winning Palestinian American journalist and author Sarah Aziza. She was born in the United States as a daughter and granddaughter of Palestinian refugees from Gaza. Her new book is called The Hollow Half: A Memoir of Bodies and Borders. In it, she examines her recovery from anorexia, that she nearly died from in 2019, as part of the generational trauma experienced as part of her Palestinian family’s history of exile.

We welcome you to Democracy Now! It’s an honor to have you with us. The Paris Review just published an excerpt of your new book, The Hollow Half. Congratulations on its publication. You have this quote, “You were dead, Sarah, you were dead.” In October 2019, you entered the hospital. You were suffering from anorexia. Many believed it could be fatal for you. And that is not only so real in your body, but it has also become a metaphor for what you describe, your family, the post-traumatic stress disorder from what’s happening in Gaza. Can you lay out what happened to you and how you broadened that to your family and people’s experience?

SARAH AZIZA: Yeah. Thank you so much, Amy. It’s an honor for me to be here. Thank you for your work.

Yeah, so, the story does start with my body sort of being shattered and nearly erased by this mental health issue that I was dealing with, that I thought, you know, according to the medical Western model, I accepted the diagnosis that this was an individual disease, something I needed to wrestle with and recover. But as I sort of trace in the book, even beginning in the hospital, I began to recover memories of my Palestinian grandmother that led to a curiosity, a deeper curiosity, about my family’s history in Gaza, in Palestine, the greater Nakba. And as a daughter of the diaspora, I hadn’t tied my own story so viscerally to the story of my people. Of course, I knew it, but sort of the understanding that many people in the diaspora have is we have crossed this threshold, this border — right? — whether it’s a temporal border or a geographical border, of “We’re the safe ones. We made it out. And, you know, we pray for Gaza, we maybe organize for Gaza, but somehow we’re a little bit more protected here in the United States.”

But what this book really examines is both the incredible inspiration that I directly draw from my grandmother, who was an illiterate, disabled, small woman who survived the Nakba, the 1967 War, was displaced from Gaza, you know, sort of the kind of woman that’s not held up to us in the United States, or even, you know, maybe in broader culture, as a hero and as a model. I was following the model of the American dream, the meritocracy. I believed that if I could advance myself, you know, I can make my baba proud, I can make my grandmother proud, but I didn’t need to tie my own story so directly to her. But what I realized was that her suffering and her loss, but also her resilience, carried some of the keys that I needed to recover from my individual malady and sort of reorient my life with Gaza and Palestine at its center, rather than falling for, I guess, the line of the American dream, which ends up being hollow and betraying most all of us, as your guests today sort of laid out in some very real, present ways.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Sarah, could you talk about the title, The Hollow Half?

SARAH AZIZA: Of course, yeah. I mean, as I was just sort of alluding to, the hollowness is — there’s many dimensions to it, I think. One of them is the hollowness of the hunger — right? — and the anorexia that the book begins with, but it’s also the hollowness of the American dream. And it’s also the hollowness of this idea of halfness, this idea of being half-American, half-Palestinian. By the end of the book, I’m sort of rejecting that. I’m sort of coming to understand that Palestinianness is a whole identity, and it speaks to every part of my life, whether I’m in the diaspora or outside of it. So, yeah, it kind of unfolds the further the book goes along.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And as someone who works with translation from Arabic into English, you write about the Arabic word dhikr for “memory.” Can you talk about how memory in Arabic is a living thing?

SARAH AZIZA: I love that question. Yeah, the fourth chapter is named after this Arabic word dhikr, which means both to remember and to invoke. So, the book begins with memory. It begins with recovering from the archive and the family archive all that was sort of lost or left behind as my family moved from their ancestral home, which was destroyed and ethnically cleansed in 1948, into Gaza, and then, after the ’67 War, out of Gaza into Syria, Jordan and eventually Saudi Arabia. So, this is a form of memory — right? — recovering from history what was erased or written over or discarded by the powers that be.

But dhikr also means to invoke, so it was sort of an answering of a call, a calling back to Palestine, realizing that Palestine really invokes the value system that I want to adopt as a Palestinian, but also anyone who seeks to defy empire and search for a different future for all of us. I think we’re seeing every day how pressing and urgent the need for a different future is. So, it’s an invocation, as well as a remembering.

AMY GOODMAN: Sarah, can you talk about how you’ve kept in touch with your family in Gaza now, sharing their messages with the world? Talk about people like your cousin Nabil and how you’ve been translating his writing and his poetry.

SARAH AZIZA: Yeah, thank you for bringing my family into this conversation. Yeah, the book was — I started writing it in 2020, but I was still finishing it in 2023, when the genocide escalated, you know. We could the genocide has been going on for decades, but — so, yeah, we have a lot of family in Gaza. My family has lost, in the greater, like, extended family, over 200 people. But there’s a —

AMY GOODMAN: Where do they live?

SARAH AZIZA: They were in Nuseirat refugee camp, Deir al-Balah, some of them in Khan Younis, also in Jabaliya, so all over. Of course, it’s been unspeakably heartbreaking and horrific and a deep challenge to find words. Actually, the dedication of this book is “For Gaza, words fail.” So, I wrote this book, but I also recognize the limits of language.

But as you, you know, beautifully brought to our attention, I did translate some of my cousin Nabil’s poetry. He’s been sending these missives to me and my parents quite frequently from Gaza. And, you know, he’s a pharmacist, actually, but lost his job, of course, in all the destruction. But it turns out he’s a poet, as well, the ways that he speaks of his despair some days, his hope other days, his pain, his hunger, most recently, in this increasingly intense famine that he’s facing.

It was a gift to be able to publish some of his words. I hope to do more. As a Palestinian in the diaspora, I mean, I’m honored to have a book out. My cousin Nabil even messaged me, saying they were proud, they feel remembered. But I think it’s always so important to point back to the voices in Gaza, so I hope to do more of that, you know, as my career goes on. I want to elevate and translate and bring Palestinian voices from inside the land to the broader community, yeah.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Could you talk, as well, about your cousin Haneen, who was 26 years old and set to graduate from college a few months after October 7, 2023?

SARAH AZIZA: Of course. Yeah, Haneen is Nabil’s sister. She’s also just this incredibly precious soul. She’s continuing, you know, to send us messages, as well. But yeah, she was getting ready to graduate from college, having survived so many wars and still being able to continue her education, then higher education. When the war started and they were displaced for the first time, she brought her graduation gown and cap with her, you know, as they fled from one place to another. And I think that just speaks to this duality that Palestinians, particularly in Gaza and the greater historic Palestine, have to hold constantly. It’s the same hope that drove my father to continue to overcome one obstacle after another, as I trace in the book.

So, Haneen is just such an inspiration to me. She has continued to educate her younger brothers, you know, sort of like homeschool them throughout these displacements. And I spoke to her on the phone somewhat recently, not as recently as I would have liked, as it’s difficult. But, you know, she still has high spirits most days. I know it’s — I don’t want to sugarcoat it. Resilience is a complicated thing, and it has its limits. But I would love to be half the woman that she is someday.

AMY GOODMAN: Sarah, you write in your book about your father and grandmother’s return to Gaza, to the smell of the sea, to the moment of joy. Can you talk more about their experiences, and how you experience Gaza here? You were actually born here.

SARAH AZIZA: Yeah. Thank you. That’s one of my favorite parts of the book, getting to reconstruct this moment. My father was born in Deir al-Balah, Gaza. And then, in '67, when he was 7 years old, they were displaced to Saudi Arabia. But then, as a teenager, he and his mother went back to visit Khan Younis and Deir al-Balah. And, you know, just this moment he describes of — you know, he was living in Saudi Arabia, so around other Arabs, speaking Arabic, but when he crossed over and began hearing the Gazan dialect and smelling the sea, his body remembered the sea, maybe in ways he didn't even know he was carrying. So, you know, he just described this feeling of aliveness, this familial sense of “I’m with my people again.” He said, “I wanted to run to run each one and take their hand and tell them, ’I’m one of you. We’re family.’” And from there, you know, he discovers, as a young man, Palestine all over again, because this is a diaspora experience of trying to get as close to our land and our history as we can, with one set of obstacles after another, and each year and each decade it gets harder.

But yeah, so, I also got to revisit Palestine several times, using the privilege of my American passport. I spent a few months in Nablus. And then my brother, father and I were able to find the traces of our family village, which was destroyed in 1948. It’s in rubble. The cemetery was razed by either bulldozer or tank, but there are still traces. And I think Palestinians everywhere are finding whatever way they can to continue to connect to that history and to bring that history into the present and to use that history to inform our hope for the future.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Yeah, and I’m wondering if you could talk some about your — the emotional changes that you’ve gone through as you see now the Israeli war, the massacres in Gaza continuing, and the rest of the world refusing to do anything substantive about Israel, and also being here in the United States, where anyone who protests this genocide is immediately criminalized and persecuted, whether it’s by universities or the government or even sometimes the media.

SARAH AZIZA: Absolutely. Well, again, this is one of the reasons I appreciate this programming, is it’s a place where I’ve seen courageous reporting and elevating of Palestinian voices, when I’m not seeing a fraction of what we need to see. So, thank you again.

Yeah, again, it’s been horrific. It’s been — it feels like a privilege to even talk about how horrible it’s been for me, because I know nothing compares to what the Palestinians in Palestine, and specifically Gaza, are going through. But it’s propelled me to dedicate myself ever more to these stories, to preserving and defending all the beauty and the abundance that is Palestine. You know, we are more than a genocide. We are more than Nakba. So, it’s, again, that duality of — in this book, there are many moments of joy and lushness and abundance, but also these moments of horror and heartbreak. And, you know, that’s really just a small example of the larger scale of the Palestinian experience that you speak to.

I think the last almost two years now has been this strange sense of déjà vu, but on a scale none of us ever wanted to imagine. There’s this sense of the externalization of history, like this thing that I knew in my body and carried in my body, in my DNA, you know, of there is a force that’s trying to erase us from the Earth. There is a force that wants to silence our stories, that wants to silence anyone who would speak out in solidarity with us. It’s been a very lonely and isolated sort of experience being a Palestinian in the U.S. — again, not to privilege my suffering.

But I think the world is starting to see what Palestinians and those who have been paying attention have always known, which is Zionism is a relentless and totality — like a totalizing project. It won’t stop until we’re erased and we’re gone. And there is no amount of nuance — there’s not a modicum of nuance to Zionism. And as the U.S., which is also a Zionist country, has doubled down on its Zionist policies and intentions, both under Biden and now under Trump, I think that the lines are just clearer than ever. Yeah, I hope that people understand, if they didn’t before, that Zionism, as well as just like the U.S. imperial project, is a project of anti-life. You know, there is no life for Palestinians, and there’s no life for many of us, as long as these projects are allowed to go on.

So, I commend the courage of the students and the journalists and the academics and the everyday people on the street who have been standing with us. And I just hope that we can continue to push forward, because any hope that Palestinians have, it begins, first and foremost, with the people on the ground resisting the absolute brute force of empire, which is coming to bear with everything it has on Gaza, but also here in the U.S., that we need to stay steadfast.

AMY GOODMAN: And what has it meant to you that so many of those, for example, who have been arrested have been Jewish, that Jewish solidarity with Palestinians fighting what is taking place?

SARAH AZIZA: I mean, I think it just completely cuts out at the knees this argument that anti-Zionism is antisemitism. I think that, again, that’s such a disingenuous argument. It always has been. You know, actually, the PLO Charter in the 1960s that they issued, you know, sort of — this is the resistance group that was resisting Zionism. They said that anyone who is Jewish who lived on the land originally was considered Palestinian. You know, this is like — we’ve always been a pluralistic society, a multifaith society. Again, this idea that it’s a religious war or an antisemitic project, absolutely false. Of course, there’s been — you know, there’s an ancient Jewish community on historic Palestine. This is, you know, not about the identity of those that are massacring us, but it is about the massacre itself. Massacres, genocide, ethnic cleansing, imperialism, these are wrong, no matter who is perpetrating them. And we are ready to work, as you mentioned, hand in hand with anyone of any identity who wants to stand in solidarity. So we’re grateful for those partners.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to thank you so much for being with us, Sarah Aziza, the Palestinian American journalist and author. Her new book is just out. It’s called The Hollow Half: A Memoir of Bodies and Borders.

That does it for our show. Democracy Now! is currently accepting applications for an individual giving manager to support our fundraising team. You can learn more at democracynow.org.

Democracy Now!_ is produced with Mike Burke, Renée Feltz, Deena Guzder, Messiah Rhodes, Nermeen Shaikh, María Taracena, Tami Woronoff, Charina Nadura, Sam Alcoff, Tey-Marie Astudillo, John Hamilton, Robby Karran, Hany Massoud, Anjali Kamat, Safwat Nazzal. I’m Amy Goodman, with Juan González.

Media Options